Barely three months before the first phase of voting for the 2014 Parliamentary elections, when the Congress party was busy explaining the perils of a Narendra Modi Prime Ministership, then Union Agriculture Minister Sharad Pawar set the cat among the pigeons when asked about Manmohan Singh’s statement that it would be disastrous for the country if Narendra Modi became Prime Minister—Pawar said: “I make it a point to use words cautiously when speaking about both my friends and my opponents.”

Veteran Journalist Rajdeep Sardesai cites an oft-quoted saying in Mumbai’s political circles about Pawar and his brand of politics: What Pawar thinks, what he says, and what he does are three entirely different things. A closer look and analysis of Pawar’s political life spanning over five decades will reveal how aptly the statement defines Pawar’s brand of politics.

Pawar’s remarks on how he is cautious when speaking about friends and foes, in early 2014, might have raised eyebrows in the Congress party but more importantly, his remarks on poll eve were an exception to his brand of politics as it exactly matched his thoughts and deeds.

Pawar, for all his ‘secular’ credentials, was happy to offer the BJP his party’s unconditional support after it fell short of the majority mark in 2014 Maharashtra assembly polls. Perhaps, that explains how Narendra Modi can call Sharad Pawar’s party “Naturally Corrupt Party” and yet confer upon him India’s second highest civilian honour, Padma Vibhushan.

In her book Maharashtra Maximus: The State, its people and politics, Sujata Anandan shares an interesting incident that offers an insight into this aspect of Pawar’s politics:

’The first to pop out of Pawar’s antechamber was Ajit Wadekar, well-known cricketer of yesteryears. He was as startled to see me as I was to see him. Only a couple of days earlier I had met the man at his office, and he had made several unkind and uncharitable comments about Pawar. As it happened, the Maratha warlord was contesting elections to the Mumbai Cricket Association (MCA), and Wadekar had been propped up by the Shiv Sena to give him a run for his money. However, Pawar preferred to be elected to the post unopposed and the meeting with Wadekar was a step in that direction’’

Pawar was elected unopposed after Wadekar withdrew his nomination. Anandan writes that when she probed Pawar about how he had managed to convince Wadekar, all he would say was, “Everything could be resolved by sitting across the table with each other.”

Sharad Pawar first cut his teeth in politics as a student leader in Pune’s BMC College in the early 1960s. Pawar’s interest in politics barely came as a surprise as his mother Sharada Pawar was actively involved in the leftist movement in the state as a member of the Peasants and Workers Party (PWP). However, instead of following the footsteps of his mother and elder siblings in joining the PWP, Pawar chose the Youth Congress. His close-aide and college mate, Vithal Maniar (who is now one of Lavasa’s directors) recollects a young boy coming from an agricultural family campaigning to be the student representative for 300 odd students. He writes, “Most of us hailed from business families and we thought this boy from a far-off village would not stand a chance in the polls but he won by polling more than 80% of the votes.”

During the Chinese invasion of 1962, Pawar, as the student representative of the University, organised a rally of 20,000 students to Pune’s Shaniwarwada. Pawar was slowly and steadily rising through the ranks of the Youth Congress. After joining the Youth Congress in 1957, within five years Pawar was appointed as the Joint Secretary of the Maharashtra Pradesh Youth Congress. He was soon spotted by then Maharashtra Chief Minister Yashwantrao Chavan who was impressed by Pawar’s speech at a College function. With Chavan’s backing, Pawar secured a ticket to contest his first assembly election from Baramati, which he won comfortably with a margin of 18000 votes. Five years later, after winning his second assembly election, he became one of the youngest ministers in the cabinet of CM Vasantrao Naik, getting the much sought-after Home portfolio.

To become Maharashtra’s Home Minister at the age of 33 is a feat that not many politicians have achieved. But Pawar had set his eyes on something much bigger- the Chief Minister’s chair of the country’s third largest state. After the total wipe-out of the Congress in the 1977 parliamentary polls and Indira Gandhi splitting the party for the second time in January 1978, Pawar had joined Congress (U), a breakaway faction of the Congress consisting of several legislators from the states of Kerala, Karnataka, Maharashtra, led by then Karnataka CM D Devraj Urs.

The 1978 assembly polls threw up a fractured mandate with the Janata Party emerging as the single largest party with 99 seats. The two factions of the Congress—Congress (I) and Congress (U) joined hands to form the government under the leadership of Vasantdada Patil. The uneasy, unstable alliance was bound to crumble and sensing an opportunity to fulfil his Chief Ministerial ambitions, Sharad Pawar split the Congress (Urs) and took away 38 of the party’s 69 MLAs to form the Congress (S). At 38, he stitched together a ragtag coalition of disparate elements like the Janata Party, PWP and the Congress (S) to become the state’s youngest CM. The coup d’etat was the first of the many ‘Pawar Play’ moves and it became a part of the political folklore in Maharashtra.

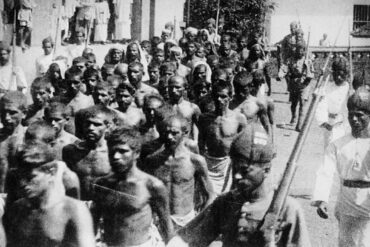

So, it wasn’t surprising to see several commentators drawing parallels between Pawar’s 1978 coup and Ajit Pawar’s 80 hour fling with the Devendra Fadnavis-led BJP after the recently-concluded Maharashtra polls. Pawar’s uneventful tenure came to an end in 1980 when Indira Gandhi dismissed his government after her return to power. Pawar’s government received a lot of flak for its alleged inaction and failure to protect the Dalits during the anti-Namantar (Renaming movement) riots in Marathwada. For sixteen years, the state’s Dalits groups were running a campaign to rename the Marathwada University as ‘Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar University’. The move was met with fierce resistance from a section of Marathas—the state’s politically most influential community.

Several Congress governments had refused to give in to the demand of renaming the University fearing a backlash from the Marathas that made up for more than 30% of the state’s electors and constituted a major chunk of the core voter base of the Congress in the state. Pawar’s government in 1978 initiated the process of renaming the University and in 1994 after returning to power, Pawar in a balancing act of sorts, decided to rename the University as ‘Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University’ to placate both the communities.

Pawar’s ambitious attempt of social engineering, to bring Marathas and Dalits—two communities that have not seen eye to eye—failed miserably. The Dalits could not forget the failure of Pawar’s government to protect them when they were massacred by murderous mobs in more than 1000 villages of Marathwada.

The Maratha strongman also lost a section of the Maratha vote to the Shiv Sena. Thackeray, unlike Pawar, was not a Maratha leader, but when he sensed a growing sense of discontent among the Marathas, he decided to jump in the mix, opposing the renaming of the University, a move that paid-off and aided the installation of the Sena-BJP government.

Pawar’s political graph started declining steeply in 1980. After dismissing Pawar’s government, the Congress (I) stormed to power winning 186 seats in the 288-member state assembly. Earlier that year, Pawar received a setback on his home turf of Baramati when the Congress (I) candidate emerged victorious.

The massive sympathy wave in the aftermath of Indira’s assassination worsened things for Pawar’s Congress (S), as the Congress (I) improved its tally in Maharashtra picking up 43 out of the 48 seats on offer. From 1980 to 1985, the Congress (I), in a space of five years, had had as many Chief Ministers. But the opposition led by Pawar had to once again eat the humble pie as the Congress (I) won more than 160 seats in the 1985 assembly polls.

Perhaps the successive defeat made Pawar realise that he had to go back to the Congress. With Indira Gandhi no more and Rajiv at the helm of affairs, Pawar returned to the Congress party. Less than two years after his re-entry, internal bickering in Congress helped Pawar to once again occupy the Chief Minister’s chair. Pawar’s main mission during his second term was to overcome the challenge posed by the Shiv Sena which was expanding into the hinterlands of Maharashtra and slowly emerging as the principal opposition party in the state.

In the mid-80s, the Shiv Sena made a paradigm shift in its strategy from region to religion and stitched a saffron alliance with the BJP on the common poll plank of Hindutva. Pawar led the Congress in the 1989 parliamentary polls and delivered 28 seats for the party. In the 1990 assembly elections, the Pawar-led Congress (I) marginally fell short of the majority mark of 144 but Pawar returned as the CM with the backing of a dozen independents.

Most political commentators don’t fail to recount how tactfully Pawar engineered splits in the Congress in 1978 and 1999 but they fail to recollect how he had split the Shiv Sena into two in 1991, seriously denting the state-wide expansion plans of the Sena. Pawar wooed Thackeray’s trusted aide and blue-eyed boy Chhagan Bhujbal. It did not matter that Bhujbal as a Sena MLA had once single-handedly stalled the proceedings of the state assembly and accused Pawar of being involved in several land-grab scams. Bhujbal’s exit was a double whammy for the Shiv Sena—it lost a prominent OBC face and a firebrand leader who was spearheading the party’s expansion plans.

Pawar’s relationship with Rajiv Gandhi is often described as one ‘based on mutual distrust’. In 1990, several Congress ministers resigned from Pawar’s cabinet and it looked as if Pawar’s government was on its way out. Pawar writes in his memoir, “I got a call from Delhi that I should come and see Rajiv. ‘What’s happening?’ he asked me. I looked at him and said, ‘Why are you asking? They acted on your instructions and couldn’t muster support.’ He said: ‘I told them to shake the tree, not uproot the tree.’ We put it aside and campaigned together in the next election.’’

Rajiv Gandhi’s untimely death in 1991 triggered prime ministerial aspirants in the Congress. Arjun Singh, Naryan Dutt Tiwari, Madhavrao Scindhia, Rajesh Pilot, Sitaram Kesri, PV Narsimha Rao, Shankar Dayal Sharma were all in contention for occupying the PM’s chair. Pawar and his henchman in Delhi Suresh Kalmadi had started lobbying soon after the results were declared. A dinner at a five star hotel was organised to elicit support for Pawar and invites were sent to the newly elected Congress MPs. Only fifty odd Congress MPs showed up. Industry stalwarts from Bombay were also lobbying hard for their ‘friend’.

Sharad Pawar’s flirtations with industry bigwigs started after the Bombay Congress leader Rajni Patel introduced him to several big businessmen. Pawar faced the fiercest opposition in his bid to be PM from Arjun Singh, the man who had facilitated Pawar’s ghar-wapsi in the Congress in 1986. In his book, 24 Akbar Road, senior journalist Rasheed Kidwai writes,

“He (Pawar) had no rapport with Sonia. When he tried to break the ice by narrating how he was the first to have discovered the ‘Italian connection’ by being the first to sign an MoU with an Italian wine manufacturing company in the 60s, Sonia was not impressed.’’

Pawar eventually lost out to the low-profile P V Narsimha Rao after Vice President Shankar Dayal Sharma refused to take over and, just like his mentor Y B Chavan, missed the opportunity to be the first Maratha to capture Delhi’s throne. And like his mentor, he went on to hold the Defence portfolio in Rao’s cabinet. Two years later, when riots broke out in Bombay in ‘92-93 and the incumbent Congress Chief Minister Sudhakarrao Naik was blamed for failing to diffuse the situation, Rao dispatched Pawar to Mumbai.

Pawar’s fourth tenure started off with 12 serial blasts ripping apart the city of Bombay. Pawar claimed 13 bombs had gone off, including one in the predominantly Muslim locality of Masjid Bunder. Years later, he admitted that he had lied in order to avoid another communal carnage against the Muslims—there had been only 12 blasts.

Pawar’s fourth term as Chief Minister was fraught with controversies. Gangsters Pappu Kalani and Hitendra Thakur were given tickets to contest the assembly poll. When they were arrested, Pawar had reportedly instructed the cops to refrain from giving them the third degree. G R Khairnar, an official in the BMC, sensationally alleged that he had proof to establish Sharad Pawar’s link with Dawood Ibrahim.

The maverick lawyer Ram Jethmalani sensationally claimed that Pawar had refused to accept conditions put forth by Dawood who was ready to surrender. The opposition latched on to the issue during the 1995 polls and Raj Thackeray’s parody, “PM tera CM (Pawar) Deewana, Hay Ram Dawood ko daale daana” had become a crowd favourite during the rallies of the opposition. Pawar led the Congress to its lowest tally of 80 seats. The Sena- BJP government stormed to power.

Next year, Pawar contested and won the Lok Sabha polls from his home turf of Baramati marking a shift of strategy: the Maratha Satrap was now relocating his political base to Delhi. The same year he made a bid to be the Congress President but lost out to veteran Sitaram Kesri.

After being ousted as the CM and losing out to Kesri, Pawar received a shot in the arm when he was made the Leader of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha. But Pawar knew that with Sonia Gandhi in the driver’s seat, he would never become the Congress party’s prime ministerial candidate. And thus the NCP was born.

Pawar displayed his political acumen by using his influence over the co-operatives headed by his supporters to bring several Congressmen linked with the sugarcane business to the NCP’s fold from Western Maharashtra. Pawar’s hopes to do a ‘Deve Gowda’ in 1999 were dashed when his NCP could only manage 9 seats and the Vajpayee-led BJP formed a stable coalition government.

In the assembly polls held later that year, the NCP won 58 seats while the Congress won 75 seats. Pawar had proven that the Congress could not win the state without him but he was nowhere near the majority mark. Throughout Pawar’s five decade long political career, his insatiable desire to stay in power has prevailed over his so-called convictions and principles and he has not shied away from hugging the enemy for staying in power. 1999 was no exception and Pawar reportedly tried to stitch an alliance with the Sena-BJP but the Shiv Sena supremo vetoed the proposal knowing that Pawar would call the shots from behind the scenes if such an alliance materialised. Left with no choice, Pawar went back to the Congress and formed the government in the state.

Pawar’s NCP joined the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government in 2004 and, he took over the reins of the Ministry of Agriculture, a portfolio he held till 2014. Pawar’s NCP remained firmly with Congress in the state and at the Centre, enjoying the fruits of power. Pawar, who despised the ‘Durbari’ culture of the Congress and pulled no punches while scathingly attacking the Nehru-Gandhi family for converting the Congress into a family firm, had no qualms in launching and promoting the political careers of his nephew Ajit and daughter Supriya.

Pawar’s name has been dragged in several high profile scams: IPL, 2G scam, Nira Radia lobbying saga, Lavasa, Enron. And yet, none of the charges have derailed his political career. Why?

The answer may lie in Pawar’s ability to be able to be on good terms with politicians across party lines, even his bitter opponents. That has enabled Pawar to do business with anyone and everyone. The NCP without power is like a fish without water. The mass exodus of MLAs on the eve of the assembly elections explains how crucial it is for the NCP to stay in power to survive.

While journalists went gaga over visuals of Pawar delivering a speech despite the heavy downpour at a rally in Satara, they were forgetting that this was the NCP supremo’s desperate attempt to keep his flock together. The old warhorse eventually outfoxed the Modi-Shah combine to install Shiv Sena’s Uddhav Thackeray as CM, but only after Ajit Pawar’s misadventure that was initiated by the senior Pawar himself in trying to keep a line open with the BJP.

The million dollar question as Ajit Pawar takes oath as deputy chief minister for the second time in as many months is, will history repeat itself and the junior Pawar emulate his uncle, this time possibly with the senior Pawar’s blessings and, get back with the BJP once again after the false start?

As things stand, it is unlikely Pawar would cut a deal with Prime Minister Narendra Modi and sacrifice his newfound glory after suddenly finding himself propelled to a larger than life role—especially in the backdrop of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the National Register of Citizens (NRC) on the anvil—at least in the short term.