At 8 a.m. in San Diego, USA, author Nemat Sadat awakens. As he has a cup of coffee, he switches on the TV and watches the news. Not surprisingly, it is all about the coronavirus. He rubs his hand through his hair—a mix of ash blonde highlights and natural dark brown hair. Sadat is slim and tall; this is accentuated by the tight blue t-shirt that he is wearing. He sits at his desk, at his mother’s home, and switches on the laptop.

He is at work on his second novel titled, Keeping Up With The Hepburns, which is set in the present-day America of President Donald Trump. “My hero, a young gay vegan Afghan has a spiritual awakening after he meets his twin flame,” he says.

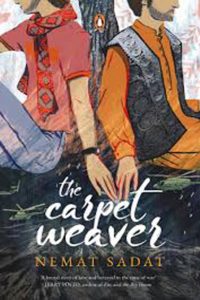

Sadat feels confident and optimistic about this book, because his debut novel, The Carpet Weaver, has been creating waves. It sold 6750 copies in the Indian subcontinent before Covid-19 brought sales to a halt. This is amazing since most first novels sell a few hundred copies only. On June 14, he will celebrate the first anniversary of its publication.

The Carpet Weaver tells the story of Kanishka Nurzada, the son of a leading carpet seller in Kabul. He falls in love with his friend Maihan. In the late 1970s and early 80s, when the book is set, until today, gays in Afghanistan face the death penalty. “In Islam, if a man loves another man it is an abomination,” says Sadat, who moved from Kabul to Germany with his parents as a baby and then resettled in the US when he was five years old. “The first line in my book states: ‘The one thing I know is that Allah never forgives sodomy’.”

Incidentally, in 68 countries, mostly in Asia and Africa, Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals and Transgenders (LGBT) are regarded as criminals. The punishment includes life imprisonment or the death penalty. Sadat felt compelled to tell this story because he wanted to be a catalyst for those who hide in the closet and the shadows.

As to why he used the name of Kanishka, Sadat says, “It was inspired by the Emperor Kanishka, the Great, who ruled over ancient Afghanistan.” It took Nemat 11 years to write the novel, as he was busy trying to earn a living. He worked as an editorial assistant at the United Nations Chronicle, as a production intern at journalist Fareed Zakaria’s popular TV show GPS, hosted by CNN and as a production assistant at ABC News’ Nightline show.

When he approached Western literary agents, he got rejection after rejection. Overall, 450 agents said no. “In the US, there is too much political correctness,” says Sadat. “They were worried about the reaction from the Muslim world. They remember what had happened to Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses [the late Ayatollah Khomeini, Iran’s de facto ruler, issued a fatwa in 1989, along with a $6 million bounty, to kill the author for blasphemy]. I am a gay, ex-Muslim, and writing about the LGBT community in Afghanistan. They felt it was safer to say no.”

Another likely reason was the negative Western attitude towards Muslims in the USA and UK deepened following the attacks on the World Trade Centre on September 11, 2001. “All Muslims are looked upon as terrorists,” says Sadat. “And after America’s difficult military experience in Afghanistan, it is regarded as a barbaric place. Anything that comes out from there is villainous.”

Finally, Sadat approached the New Delhi-based literary agent Kanishka Gupta of Writer’s Side Agency. “As soon as Kanishka read the manuscript, he said, ‘This will be a big book’,” says Sadat. “We got many offers and went with Penguin Random House India. It was the most written-about debut fiction book last year. The reviews have been positive.”

Despite that, Sadat pushed hard. He came to India and did several interviews with print, TV journalists and radio jockeys. He took part in literary festivals, at Mumbai, Delhi, and Kolkata, spoke at college functions and remained active on Facebook, YouTube, LinkedIn, Twitter and Instagram. And in November, last year, at the Tata LiteratureLive Festival in Mumbai, Sadat also hosted a writing workshop titled: Unputdownable: How to Write a Commercially Viable Novel.

Sadat had also come to Kochi in February during the Krithi Book Festival. I met him for a 90-minute chat over cups of tea and cutlets. He laughed easily, with his eyes crinkling with amusement, as he mocked the West and the anti-gay crowd.

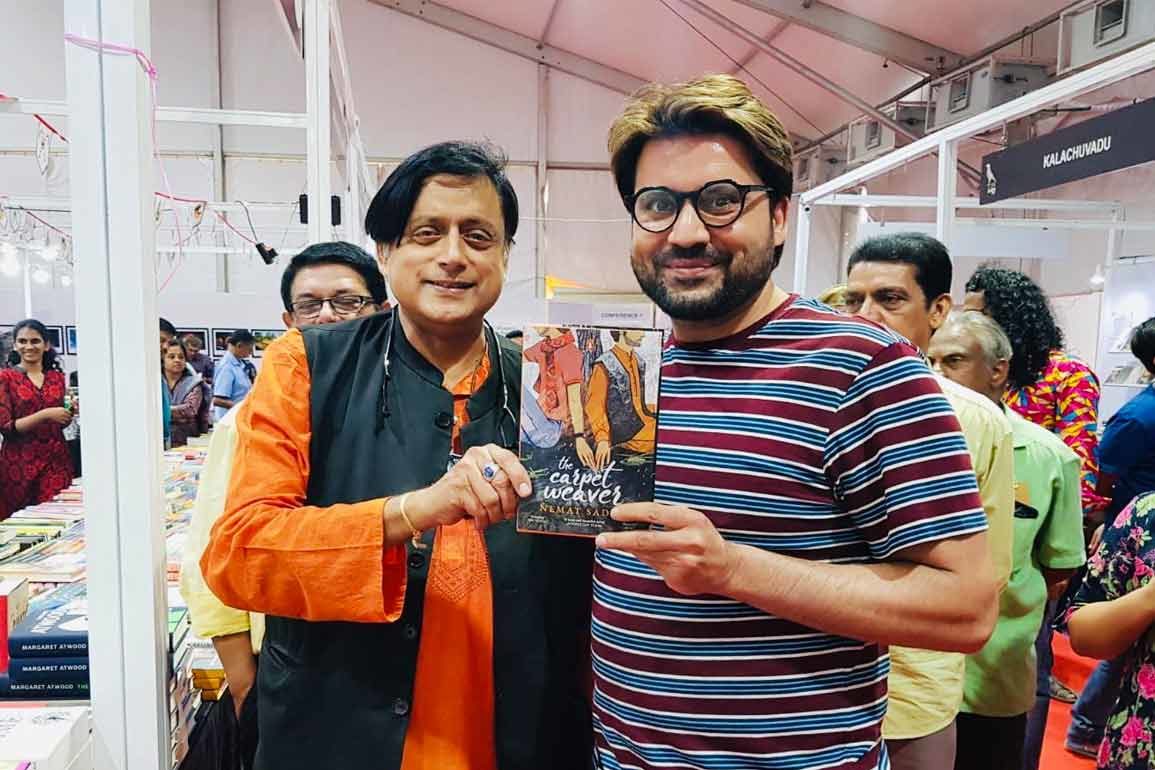

Sadat became super-excited when he had an accidental meeting with the Thiruvananthapuram MP Shashi Tharoor at the Penguin book stall. They posed for a photo with both holding the book up. While Tharoor wore a saffron juba and a black Nehru jacket, Sadat was in a striped maroon and blue T-shirt and faded blue jeans. Later, the MP tweeted about the encounter: ‘Had a serendipitous meeting with gay Afghan author Nemat Sadat, whose first novel The Carpet Weaver is making waves and has propelled him on a 55-city tour through India. Great to see young Afghans finding a new literary voice’. Sadat had then said, “Maan, he’s got 7.5 million followers on Twitter. What a boost for me.”

Asked how important marketing is for the success of a book, Sadat says, “Very important. Readers have to be aware about your book. The first 90 days, after publication, is make-or-break. But you have to write an excellent book. Otherwise, it will fall apart.”

In his travels to publicise the book, Sadat enjoyed the interaction with readers. In Mumbai, he met a woman, whose son had come out as a gay. “She had accepted it, but when she read my novel, she understood what the journey is like for a member of the LGBT community,” says Sadat. “Now she empathises with her son, not only as a mother, but as a human being.”

As for India as a country, Sadat shakes his head in wonder. “India is not a monolith,” he says. “What surprised me was the provincialism. It didn’t matter which city I visited, most people identified themselves first as Delhiites, Kolkatans, Kochiites, and Mumbaikars before they regarded themselves as Indian. Being Indian was their second or third identity. That surprised me, coming from Afghanistan and the US.”

Nevertheless, he loves the openness. “Well-read Indians, especially those who are working in the publishing business, are broad-minded and open to fresh ideas,” says Sadat. “That’s because India embraces unique perspectives. The country doesn’t have a dominant narrative, like Afghanistan, which is shaped by Islam and Pashtun nationalism or the United States, which is dominated by ‘race’, whiteness and American exceptionalism.”

However, in India today, he says, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party are trying to impose a Hindu nationalist narrative. “But in a country as diverse as India, creating such a majoritarian narrative would require many people to sacrifice their identities,” he says. “It will send India back to the days of colonialism when the British imposed an Anglo-cultural narrative. That’s why, at every turn, religious minorities and secular Indians are resisting and pushing back against the Hinduisation of India.”

Meanwhile, back in San Diego, Sadat is tapping the keys in a steady rhythm on his laptop. Words, sentences and paragraphs form on the screen. He wants to finish the first draft by May 27. Because the next day, he will resume an MA in writing at Johns Hopkins University. Of course, owing to the coronavirus, he will be doing the work online.

So, it’s eight to ten hours of writing every day, with breaks for lunch and a jog in the evening. At night, he either reads a novel or watches a film.

The literary journey of Nemat Sadat continues…