There is an old Puranic story about Truth. It seems a brash young warrior sought the hand of a beautiful princess. Her father, the king, thought he was a bit too cocksure and callow. He decreed that the warrior could only marry the princess after he had found Truth.

So the warrior set out into the world on a quest for Truth. He went to temples and monasteries, to mountain tops where sages meditated, to remote forests where ascetics scourged themselves, but nowhere could he find Truth.

Despairing one day and seeking shelter from a thunderstorm, he took refuge in a musty cave. There was an old crone there, a hag with matted hair and warts on her face, the skin hanging loose from her bony limbs, her teeth yellow and rotting, her breath malodorous. But as he spoke to her, with each question she answered, he realized he had come to the end of his journey: she was Truth.

They spoke all night, and when the storm cleared, the warrior told her he had fulfilled his quest. Armed with his knowledge of Truth, he could go back to the palace and claim his bride.

‘Now that I have found Truth,’ he said, ‘what shall I tell them at the palace about you?’

The wizened old creature smiled. ‘Tell them,’ she said, ‘tell them that I am young and beautiful.’

So Truth exists, but is not always true. That subtle insight is typical of the wisdom of the ancient Hindus. It gives the lie to the petty bigotries, the glib certitudes, the righteous fanaticism of today’s Hindutvavadis.

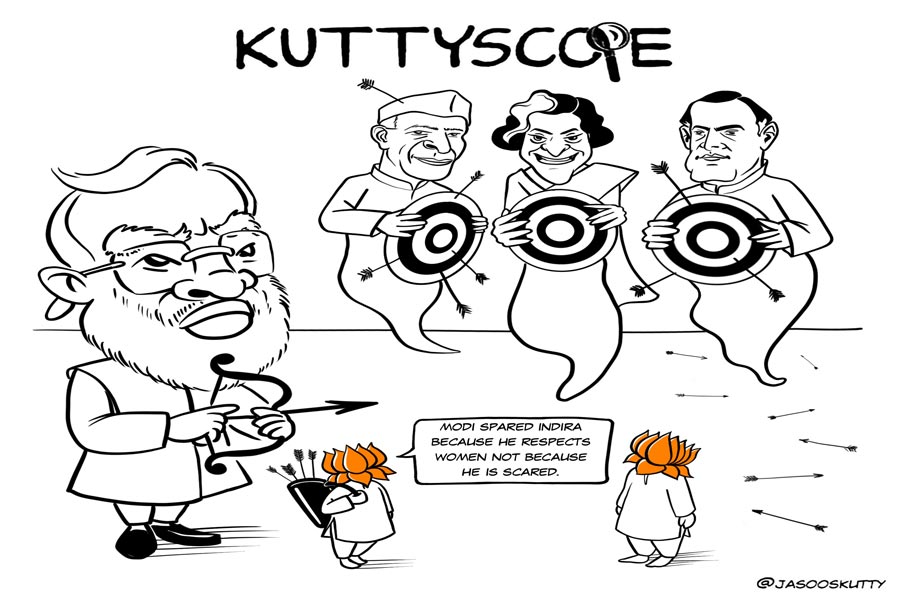

The tragedy for many Hindus is that the Hindutvavadis, often ironically referred to by their critics as bhakts (the ‘devout’), are betraying daily the values of the very faith to which they claim to be committed. Since the original Bhakti movement began in Tamil Nadu in the sixth century, Hindu thought has stressed the personal nature of religion and emphasized the inclusive philosophy and all-embracing syncretism of the faith that Adi Shankara and Vivekananda taught to the world as Hinduism. The traditional Hindu texts, starting with the Vedas, were imbued with a sense of philosophical wonder, raising questions about creation, the nature of being and the meaning of life, and treating nothing as too sacred to interrogate. It is an act of treason to Hinduism to take this faith of mystery and doubt and reduce it to brazen certitudes, to shun diversity and extol dogma and to claim that it is the only authentic Hinduism.

The political project of Hindutva is nothing less than an assault on the religion; but where Hinduism has for millennia proved its resilience to external attacks, it is now revealing its vulnerability to attack from within. That is why Hindutva politics must be resisted; in presenting a view of Hinduism that is at odds with everything Hinduism has sought to stand for, it seeks to refashion Hinduism as something it has never been. Indeed, as the economist and public intellectual Kaushik Basu has argued, it reveals the insecurity of the Hindutvavadis that they want to remake their country and religion in the very image of the countries and religions they claim to detest.

Hinduism attaches importance to pramana (instruments of warranted inference) in the pursuit of jnana, or knowledge. As long as you can demonstrate the validity or rigour of your pramana, you are entitled to the specific belief structure you wish to adhere to. It is this feature, unlike other traditions that rely on revelation as claims to truth, that ensures Hinduism is more open to diversity of belief. My friend Keerthik Sasidharan suggested to me, in twenty-first-century terms, that Hinduism is analogous to an open-source operating system on top of which others can build applications to be deployed in the receptive hardware of human brains.

All Hinduism demands before the formation of any belief is analytical and logical consistency. Even the existence of God is subject to this test. The Nietzschean formulation that God created Man and Man returned the compliment is anticipated more than a millennium ago in this verse by Udayanacharya, the tenth century logician, addressed to the deity Jagannath of Puri:

You’re so drunk on wealth and power

that you ignore my presence.

Just wait: when the Buddhists come,

your whole existence depends on me.

(Yet it should be said that Udayanacharya is the very sage credited with so roundly trouncing Buddhists in debate that Buddhism never dared to challenge Hinduism in India thereafter.)

When I became India’s first and only official candidate for the post of United Nations Secretary General in 2006, I was asked by some journalists about the role my Hindu faith played in my worldview. I conceded that it was true that faith can influence one’s conduct in one’s career and life. For some, it is merely a question of faith in themselves; for others, including me, that sense of faith emerges from a faith in something larger than ourselves. Faith is, at some level, what gives you the courage to take the risks you must take, and enables you to make peace with yourself when you suffer the inevitable setbacks and calumnies that are the lot of those who try to make a difference in the world.

So I had no difficulty in saying openly that I am a believing Hindu. But I was also quick to explain what that phrase means to me. I’m not a ‘Hindu fundamentalist’. As I have explained in this book, and said often in the past, the fundamental thing about Hinduism is that it is a religion without fundamentals. My faith in global diversity emerges from my Hindu beliefs as well, since we have an extraordinary diversity of religious practices within Hinduism, a faith with no single sacred book but many. Mine is a faith that allows each believer to reach out his or her hands to his or her notion of the godhead. I was brought up in the belief that all ways of worship are equally valid. I relished pointing out that my father prayed devoutly every day, but never used to oblige me to join him. In the Hindu way, he wanted me to find my own truth.

Excerpted with permission from The Hindu Way, An Introduction to Hinduism; Published by Aleph Book Company