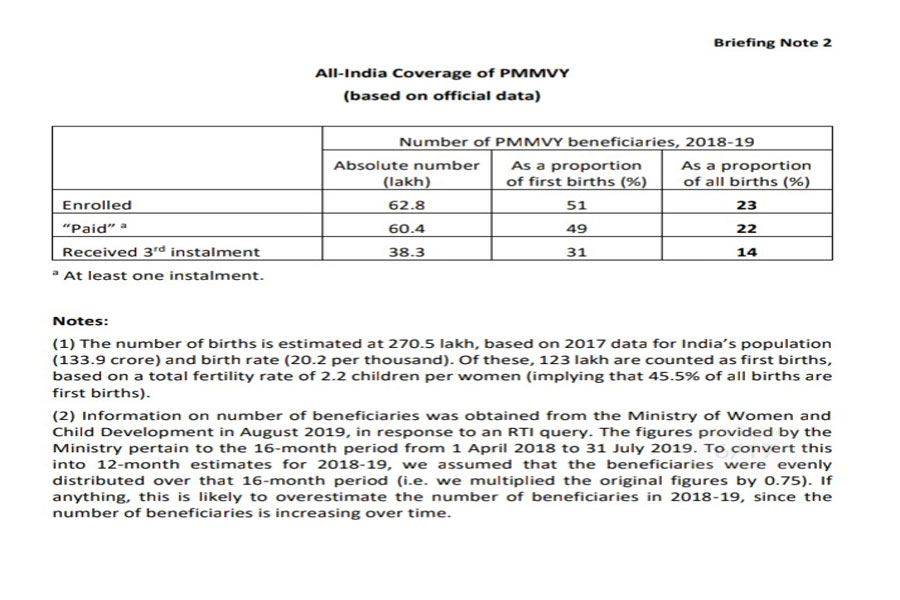

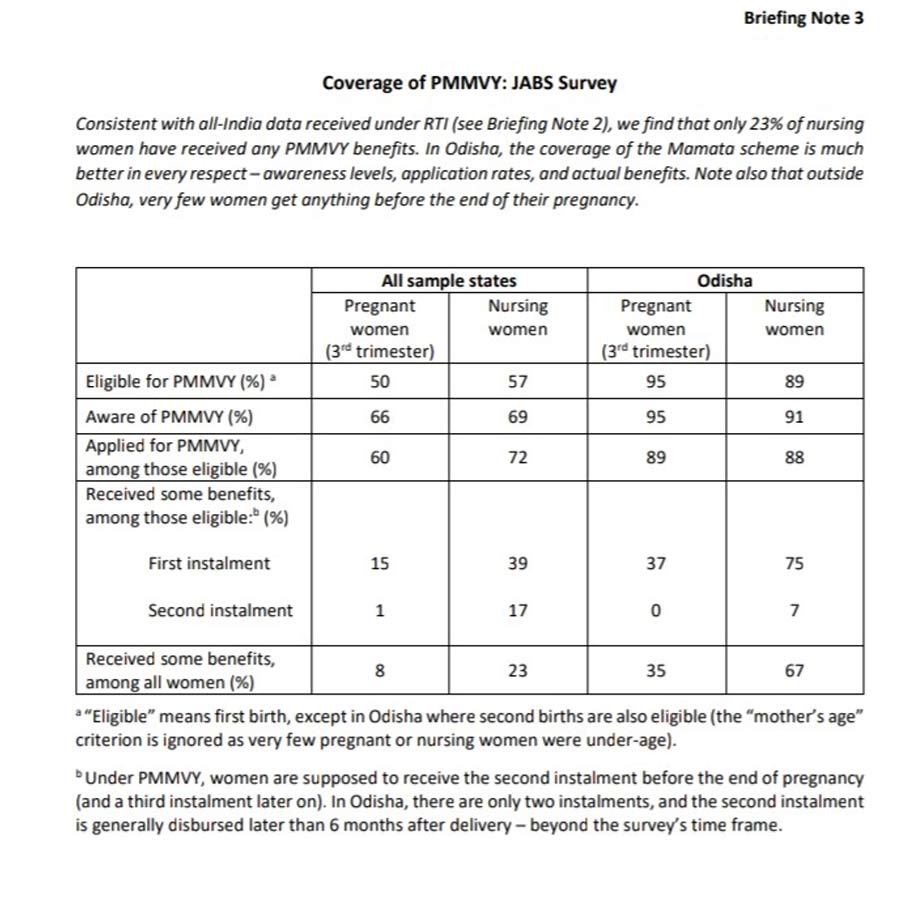

The Jaccha-Baccha survey (JABS), of pregnant and nursing women in rural India by student volunteers, coordinated by economists Jean Dreze, Reetika Khera and Anmol Somanchi, in June 2019 and released today found that expectant mothers in six states where the survey was held—Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh—were underweight (as low as 40 kg) even by the end of their pregnancy. One of the key findings of the JABS Survey was that the much-touted Pradhan Mantri Mathru Vandana Yojna (PMMVY) was restricting the maternity benefits to just one child per woman. Shockingly, the government’s own data shows that less than a fourth of eligible expectant women have received the benefits.

On December 31, 2016, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that women would be entitled to maternity benefits of Rs 6000 each after delivery. A budget allocation of Rs 2,700 crore was made in Union budget 2017-18 for the purpose. However, to cover 90 percent of all deliveries, on an assumption of a birth rate of 20 per thousand, Rs 15,000 crore would be necessary. Moreover, while drafting rules for the distribution of this maternity benefit, the Centre restricted it to just the “first live birth” and reduced the amount to Rs 5000.

Under the National Food Security Act 2013, all women are entitled to a maternity benefit of Rs 6000 for the birth of a child, unless they avail benefits as organized sector employees. The PMMVY was introduced in 2017 to implement this provision of the 2013 Act. In violation of the NFSA Act, the PMMVY restricted the benefit to just one child per woman.

Besides, the expectant mothers had to deal with the Aadhaar hassles. Over 20 per cent of respondents were unable to read; on an average, the women had been schooled only for eight years. To avail the benefits, these semi-literate women are expected to fill a form for each of the three installments of the princely sum—the form itself comes to 23 pages.

They are also expected to produce the mother-child protection card, Aadhaar card, husband’s Aadhaar card and bank passbook to avail the benefits. Many women are unaware of their entitlement, and many are left at the mercy of the local anganwadi workers. Applications filled online are often times rejected, and the reason for rejection remains a mystery.

The PMMVY expects the woman to also produce her husband’s Aadhaar card—many women could not produce these, many husbands had no Aadhaar and some were not married to the father of the child. Typos or misspelling in the Aadhaar or wrong dates of birth were all reasons for rejection too. In many cases, the anganwadi worker and the bank official too could not figure out the reason for the rejection.

The PMMVY expects the woman to also produce her husband’s Aadhaar card—many women could not produce these, many husbands had no Aadhaar and some were not married to the father of the child. Typos or misspelling in the Aadhaar or wrong dates of birth were all reasons for rejection too. In many cases, the anganwadi worker and the bank official too could not figure out the reason for the rejection.

The survey showed that pregnancy and childbirth was additional burden on rural women in these states with little support—many women, already underweight, did not even know whether they had gained weight with pregnancy. On an average, a low BMI woman is expected to put on over 13 kg during the course of pregnancy; in the six states where the survey was held, the average weight gain was only seven kg; in UP, it was four. And some women, at the end of the pregnancy, did not weigh even 40 kg. Eight percent of respondents were so weak that they suffered convulsions during pregnancy.

Student volunteers had conducted the survey at an average of about 10 anganwadis in two blocks of the same district of six states. They found, that on average, a family spends Rs 6,500 on each delivery, although these services are meant to be free at public hospitals. In many states, the minimum wage per day is about Rs 200—and the expense incurred on one delivery could be as high as a whole month’s earnings.

Student volunteers had conducted the survey at an average of about 10 anganwadis in two blocks of the same district of six states. They found, that on average, a family spends Rs 6,500 on each delivery, although these services are meant to be free at public hospitals. In many states, the minimum wage per day is about Rs 200—and the expense incurred on one delivery could be as high as a whole month’s earnings.

Women were also largely unaware of the need for additional rest and nutrition at the time of pregnancy and lactation. Many said that they had no one in the house to take over routine housework and were forced to keep working until the time of delivery. 63 per cent of women in the survey had worked until delivery. Many did not have even an older child to rely on for help.

However, there are also signs of positive change—the 108 ambulance service is widely used, pregnant and nursing women in Odisha get eggs as take-home ration, which can go a long way in correcting any nutritional deficiencies. Some women are also being fed a cooked meal at the local anganwadi, as provided for under the NFSA.

Himachal Pradesh stood out as being way ahead in ensuring better conditions for women and children; even Odisha, which for long was clubbed with BIMARU states, was making steady progress. ICDS services, the provision of eggs in anganwadis (and to pregnant women) and good coverage of insurance was making a big difference in Odisha, which also had its own scheme for pregnant and nursing mothers, called Mamata, that covered two children.

In Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, however, the situation is grim. In UP, the students conducting the survey found all anganwadis shut at the time of the survey.