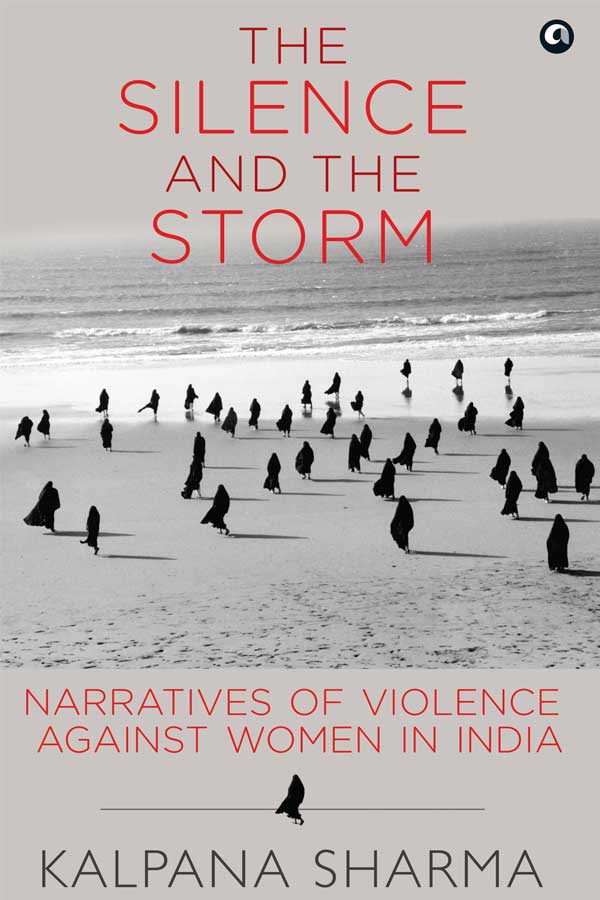

If on the basis of the testimony of the survivor, the perpetrators of the crime are caught, then the other part of the trauma begins. An illustration of this is what has come to be known as the Shakti Mills rape case. On 22 August 2013, less than a year after the furore that followed the gang rape in Delhi, and after the Verma Committee report led to a change in the rape law, a twenty-two-year-old photojournalist and her colleague were accosted by a group of men when they went to take pictures of an abandoned textile mill in Central Mumbai, a stone’s throw away from a busy railway station. The woman was gang-raped while her colleague was beaten up.

Luckily for her, even though traumatized—the rapists filmed the act—she had her wits about her. After the rapists walked with her and her colleague to the nearby Mahalakshmi railway station, where they issued dire threats that if they were to report the incident to the police, the videos of the rape would be released on social media, the woman decided to go immediately to the nearest hospital to get a medical examination. Changes in the law after 2013 established that any hospital, private or public, would have to attend to a rape survivor, report to the police and conduct a medical examination. Earlier, only public hospitals could do this.

The fact that she was a journalist, that her seniors came immediately to her aid as did other journalists, helped ensure that the police did not delay in moving on the case. The five men were soon arrested and charged. The case was heard in a fast track court and judgment delivered within six months.

It just so happened that when the news of this rape surfaced, another woman, an eighteen-year-old telephone operator, went to the police and reported that she had been raped by the same men months earlier in the same spot. As a result, the police charged three of the men, Vijay Jadhav, Kasim Bengali, and Salim Ansari under Section 376E of the Indian Penal Code that recommends the death penalty for repeat offenders. The three men were handed this sentence by the court. The fourth man, Siraj Khan, was given a life sentence as he was not involved in the earlier rape. And the fifth, a minor, was sent to a correctional facility. Although the three men awarded the death sentence appealed against it, on 3 June 2019, the Bombay High Court upheld the death sentence.

What the public did not know was the trauma this brave young woman, who knew the law, and took the necessary steps to seek justice, had to face. For one, even though the law clearly lays down that no hint of the survivor’s identity ought to be given, the media would not relent. The leading newspaper in Mumbai, the Times of India, sent reporters to the residential colony where the girl lived. They spoke to the neighbours and to the watchmen, neither of whom knew that a girl from the building had been raped. But once the media arrived, it did not take long for them to guess the identity of the survivor. Thus, the media directly colluded in outing her.

Worse still, a reporter from another newspaper climbed sixteen floors of a private hospital, where the woman was being treated, to try and get into her room to interview her. She was stopped by the police guarding the floor. What was the necessity of this kind of intrusion into the survivor’s privacy?

This has been the tragedy of the Indian media in the twenty first century. It fails repeatedly to be sensitive to the problems that rape survivors face after they have been sexually assaulted and brutalized. In the case of the Delhi gang rape, media houses realized they could not name the woman. But they still wanted to pursue the story. Constantly describing her as ‘the twenty-three-year-old woman’ or something similar was tedious. So instead, some media houses gave her a fictitious name, something she had not asked for and for which her approval was never sought. So Nirbhaya, a name that has stuck, was decided by the Times of India while Damini and some other names also floated around.

It is surprising that few questioned the decision to give a fictitious name to a living human being without seeking her permission. Or dropping it and using her real name after she died when her parents went public with it. Till today, it is unclear whether her real name can be used. So the media sticks to the pseudonym, Nirbhaya, and the government too has adopted it to launch a scheme for rape survivors. I prefer not to use a fictitious name. I would have preferred to use her real name, especially as her parents are on record revealing it and pointing out that their daughter had not committed a crime, hence why should her identity be hidden. But the law on this remains unclear; the Supreme Court has reiterated that the identity of a rape survivor should not be revealed even if she dies after the crime.

In the Shakti Mills case, the story did not remain in the news, partly because the survivor recovered from her trauma and injuries and pursued the case. There were no candlelight vigils stretching out over weeks. And the law had already been changed. Yet, despite the change in the law, the systemic problems in pursuing a case of sexual assault remained unchanged, as the survivor of the Shakti Mills rape case soon realized.

Take the identity parade, for instance. In television serials and films you are made to believe that the survivor stands behind a glass panel where she can see the line-up of the potential perpetrators of the crime but none of them can see her. She is then asked which person committed the crime. And she identifies the person on the basis of a number that each person in the line-up holds up. In India, the routine of the mandatory Test Identification Parade, when the perpetrators of a crime are unknown to the survivor, is atrocious. Here is how it is described by a close colleague of the Shakti Mills gang-rape survivor. (The names used are not of the people involved):

“The following day, on Friday, September 4, both Megha and Deepak are called in for a Test Identification Parade (TIP), where they have to pick out the accused from a line-up of similar-looking men. They are both nervous, but putting on a brave face. The police make Megha wear a burqa to avoid the cameras outside, but inside the room where the suspects will be called in by turn, she is required to take it off. A tehsildar and two more personnel bear witness to the process. Here is the routine of the identification parade that Megha is told to follow. There are separate line-ups of seven men, and the survivor has to pick the accused by touching him on the arm. She then has to go to a corner of the room, and announce loudly what the suspect did to her. And this is what Megha does on September 4, in a room full of men that include her attackers, without any women officers present to aid her. She touches the men on the arm to identify them, and then says, ‘Isne mera balatkaar kiya.’ (He sexually assaulted me). She repeats this four times over.”

The problems of the survivor do not end after she has identified the culprits. She must then face the court, and still hide her identity from an intrusive media. Cameras are everywhere outside a trial court even though the proceedings within the court room are in camera. Usually, the police do little or nothing to ensure that the survivor can enter the court without being seen by these prying eyes.

In the Shakti Mills case, a non-governmental organization, Majlis, extended support to the woman and made sure that she was guided into the courthouse through a route that would evade the media. The woman colleague, who wrote the piece quoted above, ‘That Hashtag Was My Colleague’, writes, as an insider, about the media feeding frenzy.

She recounts the many and deliberate violations of the law by practically all sections of the media that were committed during the course of the investigation of this crime: In print and television newsrooms, journalists are required not just to report personal tragedies, but to hunt for exclusives, and look for ‘human angles’ by hounding relatives and friends of those affected. Crossing the line is not only encouraged, it is mandatory.

Excerpted with permission from The Silence and The Storm by Kalpana Sharma; Published by Aleph Book Company.