With seven murders of cadres belonging to the Communist Party of India (Maoist) in three incidents in as many years, the Communist Party of India (Marxist)-led Left Democratic Front (LDF) government in Kerala is setting a dubious record of annihilation of political opponents that states like Chhattisgarh and erstwhile Andhra Pradesh, known for police actions to wipe out the Naxalite menace, have for long practiced.

But there is a crucial difference in the nature of the menace: the terror belt that covers the vast tribal regions in east and central India have witnessed many attacks on the part of the Maoists against the forces of the state, which took the form of a long-standing contest for power and control between the two. But in Kerala, the Maoists have never launched any such attacks on the state forces and, in fact, they have maintained through their public statements that they were involved only in political campaigns and no militant actions.

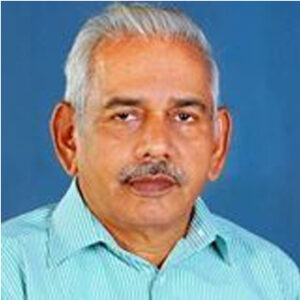

It is a fact that Naxalite groups have been active in the tribal regions in the northern parts of Kerala, especially the forest belt from Wayanad to Palakkad where all the three recent incidents have taken place. All encounters have been carried out by the members of Thunderbolt force of the Kerala police, set up during the regime of the previous United Democratic Front (UDF) government. Surprisingly, the present LDF government under Chief Minister, Pinarayi Vijayan, appears to have decided to continue the same policies of repression without any review of the violent nature of the incidents and the public condemnation of them.

This is surprising because it clearly departs from the consistent stand maintained by the earlier Left governments, which maintained that political rivals would be encountered not through police action but through negotiations and public campaigns. This was the policy the CPI (M)-controlled governments had upheld from 1967 when the Naxalite groups became active in Kerala and were involved in a number of incidents including attacks on police stations.

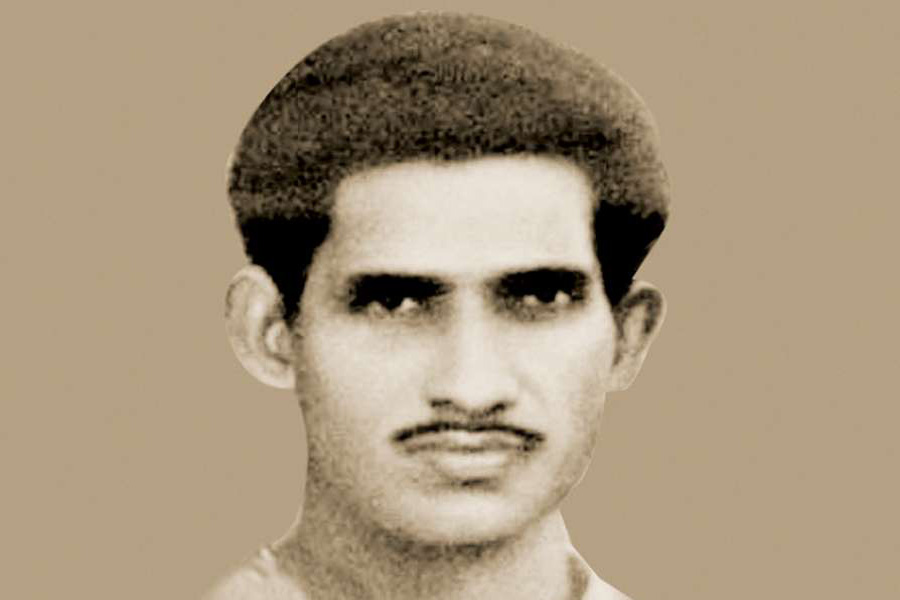

The first incidents involving Naxalites took place in the Wayanad forests in the late sixties, and it was on February 18, 1970, the first major ‘encounter death’ took place. The police reported that A Verghese, leader of the Naxalite group operating in the Thrissilery-Thirunelli forests in North Wayanad, was shot dead in an “encounter” with police in the forest.

It was the Deshabhimani daily and the CPI (M) state leadership that first rejected the government claims, asserting that it was a cold-blooded murder of a political activist. Home Minister C H Muhammad Koya had a tough time defending the police action and what came to his rescue at the time was a report in the CPI (ML) publication, Liberation, which claimed that “Comrade Varghese was shot dead in a heroic battle” with the police.

But almost three decades later, in 1998, the truth came out when Ramachandran Nair, a policeman, who was in the team that tracked down Varghese, made a confession that it was he who had shot dead Varghese from a point blank range, under orders from K Lakshmana, officer in charge of the operations. Nair was ready to face trial and receive the punishment for the crime, but he died in the course of the CBI probe and later Lakshmana was found guilty and was convicted for the same.

During the 1975-77 Emergency period, there were a number of incidents of police excesses, including the murder of engineering student P Rajan, who met with his death during police interrogation at the notorious police terror camp at Kakkayam. Congress leader K Karunakaran, who was in charge of home portfolio during the Emergency regime, was forced to resign as chief minister following Kerala High Court’s adverse comments about Rajan’s death in police custody.

It was again Deshabhimani and the CPI (M) that was at the forefront of the campaign to secure the democratic rights of political prisoners incarcerated during the Emergency. A series of investigative reports by Appukkutttan Vallikkunnu, then a reporter for the newspaper at Kozhikode, highlighted the extreme cruelty and highhandedness practiced by the police on political prisoners at Kakkayam and other secret camps where Naxalites were held without trial and subjected to torture.

Chief Minister C Achutha Menon, a veteran Communist Party of India (CPI) leader who led the CPI-Congress-Muslim League coalition government at the time had to face much criticism for the police excesses during the emergency regime. But to the credit of Achutha Menon, it must be remembered that it was he who stood firm against the implementation of the draconian legislation called Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) in Kerala at the time. He held his ground against the Congress colleagues in the cabinet, including the all-powerful Home Minister K Karunakaran, who was for imposing MISA in Kerala to enforce discipline and public order in the state, as was done in other parts of the country.

The same tradition of keeping the police on a tight leash in its dealings with political activists and public agitations continued during the periods of the later Communist governments led by E K Nayanar and V S Achuthanandan. It is true that there were unfortunate incidents of police excesses during those years, but these were aberrations.

When the present Left government under Pinarayi Vijayan came to power in 2016, the same policy had been pursued initially, going by the actions taken by the government. For example, the government had decided to review a large number of cases registered under Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) by the earlier UDF government, with dozens of youngsters being put in jail without bail in various parts of the state. Many such cases were withdrawn as they were found to be charged on flimsy grounds, the victims mostly being Muslim youngsters who were arrested for political protests with no violence involved. The application of UAPA in such cases was a wanton misuse of administrative powers, the government concluded at the time of the review.

And yet, the same government has used the same draconian legislation against a large number of political activists, the latest victims being two students who are members of the Students Federation of India (SFI) and hailing from families connected to the CPI (M). The Inspector General of Police (North Zone) Ashok Yadav who made inquiries about the arrests has asserted that the UAPA provisions against the students could not be revoked—giving an indication of the government’s resolve to use excessive powers against political activists.

The encounter of the four Maoists at Agali and the subsequent arrest of the two Marxist student activists in Kozhikode on a day when the chief minister himself was in the city indicate the change in the government’s attitude towards its political opponents.

In this new approach, what is being witnessed is the transformation of a Left government into something more like the Karunakaran regime that relied on the Police to enforce its policies. Karunakaran ruled the state with an iron hand in a different age when the plethora of violent agitations and public protests had tested the patience of a society desperate for some order and peace. But that is not the case today when democratic actions have gone to the grassroots and even the most subaltern sections have found their voice.

From the way even the CPI (M) cadres have responded to recent developments, it would appear that soon, differences on the repressive policies pursued by the government would come into the open even within the ruling party. A statement from politburo member M A Baby, who has been largely keeping out of the state affairs, castigating the police action might be the beginning of a more serious opposition from within the ruling party.

Alliance partner CPI has found its voice this time, and its assertiveness in rejecting the police claims might help garner public resistance to the repressive policies of the Pinarayi regime. For the CPI, the present position could help it regain the public trust it had lost when party secretary, Kanam Rajendran, went to the extent of castigating his own comrades for taking out a protest march against police excesses in Ernakulam recently.

For Pinarayi Vijayan, it is a new incarnation as an administrator. Does it suit him? A popular lore that can be traced to his home grounds is about a young man called Vijayan from the remote village of Pinarayi going to meet comrade A Varghese, who was once the office secretary of CPI (M) Kannur District Committee, in the late sixties. Varghese had already taken up arms when the young man inspired by the legends of Che Guevara and Telengana comrades wanted to follow him in the revolutionary path. But Varghese dismissed him, urging him to focus on his studies and political work.

Such a man has now become the epitome of use of sheer force against political opponents in a state which had elected the communists to rule them at a time when all over the world they were being hunted by the police. Now it is an irony of history that communists are being gunned down point blank, many of them women and aged people who are not able to fight back, in a peaceful state under a communist regime.