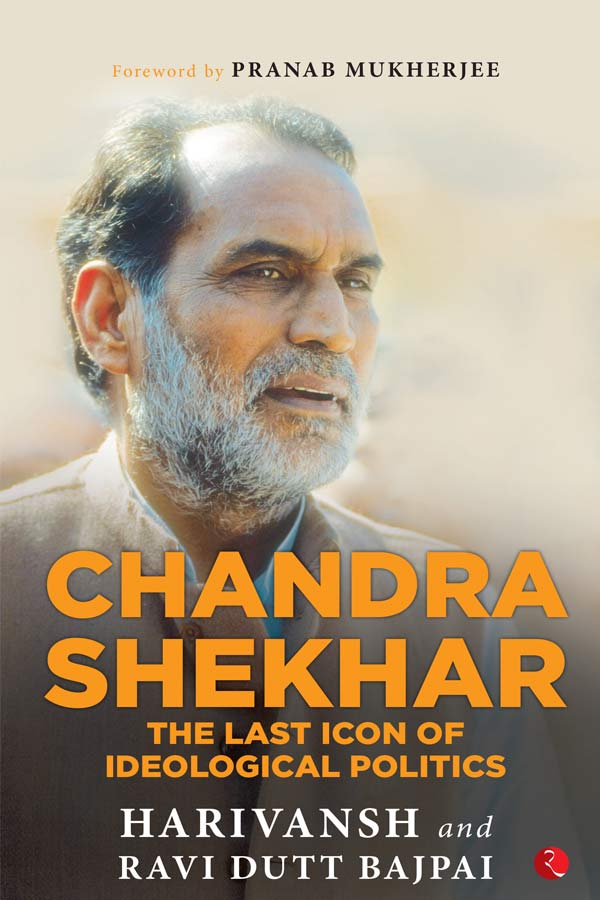

Chandra Shekhar, India’s last socialist icon, steadfastly held to his political convictions in a career spanning over five decades. As socialist politics metamorphosed into identity politics in the post-Mandal nineties, and gradually degenerated into family-run enterprises, Chandra Shekhar: The Last Icon of Ideological Politics written by Harivansh Narayan Singh (co-authored with Ravi Dutt Bajpai), Chandra Shekhar’s former media adviser and journalist, and now, Deputy Chairman of the Rajya Sabha, is a relevant read.

Harivansh Narayan Singh observed Chandra Shekhar from close quarters and this is reflected in some of his minute observations. Apart from his own interactions with the socialist stalwart from 1978, the author has relied on extensive conversations with Om Prakash Srivastava, Chandra Shekhar’s friend of over half century, and Zindagi Kaa Kaarawan, Chandra Shekhar’s biographical sketch (by Ram Bahadur Rai and Suresh Sharma) to write the book. The author’s admiration for Chandra Shekhar is clearly reflected in this biography but it does not dissolve into a hagiography

The seven chapters reveal many hitherto unknown facts and facets of a man who didn’t really get his due in Indian politics. The high point of his career was becoming Prime Minister for seven months but it would be grossly unfair to judge him by that short tenure.

Chandra Shekhar was the face of opposition through the eighties till the emergence of ‘Raja of Manda’, V P Singh, in the wake of the Bofors scandal. But long before that, Chandra Shekhar played a major part in shaping the Congress’ socialist slant in the late sixties. And he was often the lone dissenting voice to take on Indira Gandhi from within the Congress at the peak of her popularity.

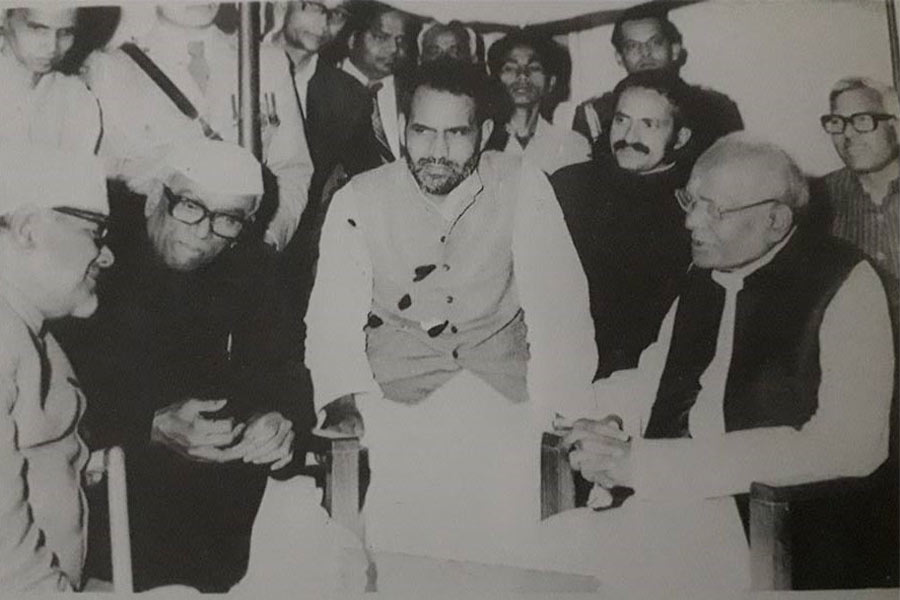

Leading the Young Turks—Mohan Dharia, Krishan Kant and Ram Dhan being the prominent others—Chandra Shekhar was the most popular leader after Indira Gandhi post the split in the Congress party. He was also the most sought after leader for campaigning (apart from Gandhi) in the run-up to the elections in 1971.

The palace intrigues and durbar culture that engulfed the Congress post 1971 soon led to the Chandra Shekhar becoming persona non grata. His efforts to mediate between Jayaprakash Narayan (JP) and Indira Gandhi to end the stand-off after JP’s call for Total Revolution or Sampoorna Kranti on the eve of the emergency have been detailed.

Having acted as a corrective force in a party afflicted by the cult of personality in the early seventies, Chandra Shekhar, a loyal Congressman, found himself behind bars along with leading lights of the opposition on the night the Emergency was declared in 1975. Apart from fellow socialist and trade unionist George Fernandes, Chandra Shekhar was the lone political prisoner to undergo solitary confinement for the duration of the Emergency. Although Indira Gandhi did try to patch up with him and sought Chandra Shekhar’s audience once the Emergency was lifted, there was no going back to the Congress for Chandra Shekhar.

In the Janata-coalition government that came to power in the aftermath of that election, Chandra Shekhar willingly gave up his claim to a Cabinet ministerial role that he was offered in favour of his fellow-Young Turk Mohan Dharia. That was just one instance of Chandra Shekhar’s deep commitment and loyalty towards his friends which is a recurring theme in the book. A rare occurrence in an opportunistic political world—Chandra Shekhar was also upright and forthright, not prone to hypocrisy like the commonplace politicians. Sometimes his straight talk stunned even seasoned politicians like Ram Manohar Lohia and Indira Gandhi.

And this diamond in the rough was definitely not a favourite of the Lutyens’ media. His humble beginnings and rustic looks only added to the prejudice. In fact, he was often given a raw deal by the media unlike their favourable treatment of Rajiv Gandhi and later, V P Singh. Although he did not get a fancy education like many of his political peers, Chandra Shekhar never allowed that to come in the way of his performance as a parliamentarian; he was known for making well-researched and nuanced speeches in the Rajya Sabha, in a pre-Information Technology age.

Chandra Shekhar’s political journey began in 1952 when he began to work as a foot soldier of the Praja Socialist Party (PSP). Post the 1954 split in PSP engineered by Ram Manohar Lohia, Chandra Shekhar remained with the faction led by Acharya Narendra Deva and worked hard on the ground to help his party perform better than the Lohia faction, eventually leading to the PSP’s N D Tiwari becoming the Leader of Opposition in the Uttar Pradesh assembly in 1957.

Chandra Shekhar joined the Indian National Congress in exceptional circumstances. He took a stand against the expulsion of socialist stalwart Ashok Mehta from the PSP in 1963. Mehta had formulated a theory—‘Compulsions of the Backward Economy’—which suggested that opposition parties should cooperate with the government on critical issues to accelerate growth in developing countries. In short, Mehta advocated PSP’s cooperation with the Congress, prompting Nehru to offer Mehta the deputy chairmanship of the Planning Commission—leading to Mehta’s expulsion from the PSP.

At the national executive of the PSP, Chandra Shekhar declared: “You terminate the membership of Ashok Mehta, and I shall terminate my membership from the national executive”. This led to Chandra Shekhar’s own expulsion from the PSP for his open support for Mehta and he joined the Congress after six months.

Chandra Shekhar’s belief that socialism could decelerate poverty was steadfast. He also took a principled stand against the favouring of certain powerful industrial houses (Birlas in particular) in granting licences. He played a vital part in Congress adopting a Left tilt in the aftermath of the 1967 elections that eventually led to its split in 1969. In fact, in his first interaction with Indira Gandhi, Chandra Shekhar expressed his desire to steer Congress to adopt a socialist path. Chandra Shekhar was also the founder-editor of Young Indian journal.

Chandra Shekhar’s inherent faith in socialism was probably a by-product of his humble origins. He even held the belief that one couldn’t really understand the problems of the poor at a molecular level if one hadn’t experienced poverty first hand or from close quarters.

Chandra Shekhar never flaunted his background or attempted to seek votes on that account like some contemporary politicians do; nor did his origins develop in him an inferiority complex. He was confident in his abilities and through his voracious reading, he had trained himself to effortlessly rub shoulders with the who’s who of Indian politics. Chandra Shekhar transcended his circumstances to emerge as a mass leader. Despite hailing from a ‘forward caste’, he represented the interests of the backward class.

After undertaking a nation-wide padayatra lasting six months in 1983, Chandra Shekhar had clearly emerged as the face of the opposition to Indira Gandhi. But, in the changed circumstances following Gandhi’s assassination a year later, all the gains he had made in the interim fizzled out as people voted for the Congress in an emotionally-surcharged atmosphere. Although some well-wishers advised Chandra Shekhar to quit active politics and adopt a JP-like position in the 1980s, Chandra Shekhar reckoned that he was too young to quit active politics in his 50s without ever getting an opportunity to hold a political office.

When he finally held a political office—as Prime Minister in November 1990 with Congress’ support, it was the culmination of a long-held ambition, albeit in unusual circumstances. Although some political pundits regard Chandra Shekhar as a power-hungry politician, his decision to form a ramshackle government with the breakaway Janata Dal (Socialist) has to be seen in the context of a man who was denied the chair time and time again.

Chandra Shekhar led the Janata Party as President for a decade from 1977 till he eventually quit in favour of the young Ajit Singh, who promptly ditched his mentor. V P Singh’s sudden rise to prominence and his carefully manufactured image as a paragon of virtue irked Chandra Shekhar. And when V P Singh hatched a conspiracy with Devi Lal and Arun Nehru to avoid a contest with Chandra Shekhar to the parliamentary party leader’s position post the general election in 1989, it further exacerbated the bitterness.

The author has reduced the 1980s to one big chapter which doesn’t do justice to the politically tumultuous decade as he misses out on a lot of relevant information with regard to Chandra Shekhar—covered in the autobiographies of I K Gujral (Matters of Discretion) and M L Fotedar (The Chinar Leaves), for instance. Apart from that, the author has documented well the life of the socialist icon.

Chandra Shekhar continued to be an active politician and parliamentarian till his death at the age of 80 in 2007 and unlike the socialist politicians of today, he never initiated his son into active politics. He was a liberal and a socialist; and, if Congress hadn’t been afflicted by personality cult and dynastic politics in the early 1970s, Chandra Shekhar would have succeeded Indira Gandhi as the leader of the Indian National Congress.