Forty-five years have passed since India and Pakistan fought a regular war, not counting the bitter and bloody conflict on the icy heights of Kargil which stands on a separate footing by virtue of its geographical setting. Most of those who are crying for war in the wake of the attack on the Uri army base are people who are too young to know about the situation at that time. They will presumably be happy to hear that similar slogans were heard then too. Mercifully, the war cries of those days were not too shrill or too loud as news channels and Goswamis and social media and cyber sepoys were not around.

The chain of developments that culminated in the war of December 1971 began at the beginning of that year with the elections held by Pakistan President Gen. Yahya Khan to transfer power to a civilian government yielding an unexpected verdict. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s Awami League secured a clear majority in the National Assembly by making a near-total sweep of the East wing seats. Pakistan People’s Party’s Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto was unwilling to concede the Prime Ministership to him and Yahya Khan lacked the courage to put national interests above the West wing’s.

Kashmiri dissidents dragged India into the developing imbroglio by hijacking an Indian Airlines plane on a Srinagar-Jammu flight to Lahore. The hijackers freed all aboard the plane unharmed. Later they blew it up. In retaliation, India denied Pakistani aircraft permission to overfly. As a result, Pakistani planes flying from one wing to the other had to go via Colombo. This severely limited Pakistan’s ability to send reinforcements to the East wing when the army crackdown of March 25 provoked a guerrilla campaign.

Some 10 million people from East Pakistan poured in as refugees, imposing a heavy burden on India. The way Indira Gandhi’s government handled the crisis holds valuable lessons for the Narendra Modi government which is trying to boost the morale of the people, particularly its jingoist supporters, with bluff and bluster.

Years later then army chief Gen. S. H. F. J. Manekshaw revealed that as early as April 1971 Mrs. Gandhi discussed with him the question of an Indian military intervention. He told her he needed time to make preparations for a successful military campaign. She granted his request. As the military prepared to confront Pakistan she launched a diplomatic offensive. India and the Soviet Union signed a friendship treaty which said in the event of an attack or threat to either country, the two shall immediately enter into mutual consultations to remove such threat and take appropriate effective measures to ensure peace and security. The Americans were not pleased with it.

Indira Gandhi’s visit to Washington in November to apprise President Nixon of the serious situation India faced with the massive refugee influx was a disaster. A declassified US document contains the transcript of a White House discussion of the time in which Nixon refers to her as a bitch and Henry Kissinger says Indians are bastards.

Curiously while India had all the reasons for staring a war, it was Pakistan that took the initiative. It was being bled by the guerrilla war and apparently thought it best to bring matters to a head. On December 3, Pakistan’s air force bombed a dozen military airfields along India’s western border, from Avantipora in Kashmir to Jamnagar in Gujarat. The bombing did not cause much damage as India, anticipating a pre-emptive strike, had moved its aircraft to bunkers. India struck back immediately. Borrowing the terms the New York Times used to report the start of the US Civil War, one can say: the ball started, war began.

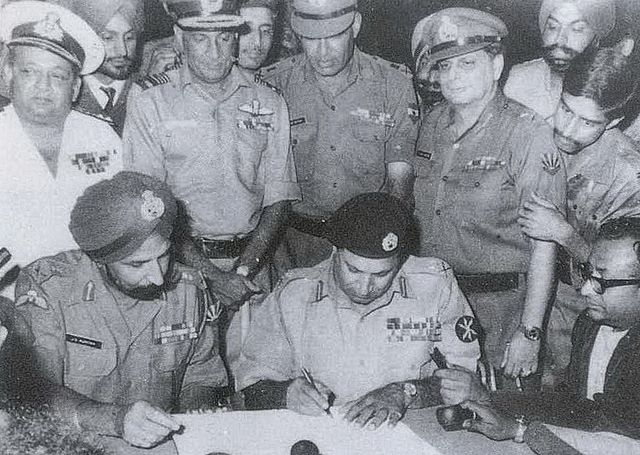

The Indo-Soviet agreement deterred China, which had raised a scare of dismemberment of Assam a decade earlier, from intervening in the 1971 war. But the USA was ready for a gamble. Nixon ordered a task force led by USS Enterprise, then the world’s largest aircraft carrier, into the Bay of Bengal with orders to target the Indian military. It entered the Bay on December 15, too late to avert Pakistan’s surrender at Dhaka the next day. At the end of the war, India had on its hands 93,000 Pakistani prisoners of war. The hostilities lasted just 13 days.

The 1965 war, which was touched off by Pakistani soldiers sneaking into the Kashmir valley to engineer an insurrection, had dragged on for 17 days. That is the maximum time the two countries could get to fight a conventional war in the conditions prevailing in those days. Within that period, two things were certain to happen. One was that international pressure on the two countries for a cease-fire would become impossible to resist. The other was that ammunition stocks would fall to so low a level as to compel the two sides to end the hostilities.

The changes of the last 45 years have not enlarged this time-frame to an appreciable degree. No sensible leadership on either side will, therefore, start a conventional war unless it feels confident that its immediate military goals can be achieved in a fortnight’s time. Since the 1970s another factor is also at work: the balance of terror resulting from the stockpiling of nuclear arms by both the countries.

Ground conditions favoured India in both the wars. The local people had alerted Indian authorities about the entry of Pakistani agents provocateurs in Kashmir in 1965. Kashmiris did not care to use the opportunity Pakistan had provided them to revolt. Dashing Pakistan’s hope that the military engagement would be confined to the valley, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri sanctioned crossing of the international border. In 1971 people in the East wing were totally alienated from the Pakistani establishment and they welcomed the Indian troops as liberators.

It was a challenging time for the media. As relations between the two countries deteriorated, contacts had shrunk. Diplomatic relations were cut off. Communication facilities too were snapped, making it impossible for people across the border to even exchange letters by post. International news agencies were the only sources of information on developments in Pakistan which were of immediate and direct interest to India, and what they provided was too skimpy. United News of India (UNI), the news agency with which I was associated at that time, was able to keep up a steady flow of information on Pakistan in that critical period by adopting unconventional methods. That is a story that deserves to be told separately.

BRP Bhaskar is a senior journalist and human rights activist. He is also a winner of Swadeshabhimani Kesari Award instituted by the Government of Kerala.

Cover Image Courtesy: Indian Navy [CC BY 2.5], via Wikimedia Commons