Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery, first published by The New Yorker on June 26, 1948 describes almost clinically the dehumanized mob behavior while a lynching happens. Though I read the short story decades ago, the horror of it has been tattooed permanently somewhere on my mind, so much so that every time I view a video of an honorable mob of gau rakshaks lynching someone for eating beef or smuggling cows—a few seconds into it—my mind veers to that short story. It’s perhaps my way of trying to comprehend the beast.

Set in an all-white, small town North America, the story unfolds around an annual event called the lottery which happens in the village square on June 27. The children come first, their pockets bulging with stones and they collect more into a heap. The men and women follow, adding up to around 300 of them.

It’s quite a democratic process, the rules are read out and everyone takes a fair chance. “There was a great deal of fussing to be done before Mr. Summers declared the lottery open. There were the lists to make up–of heads of families, heads of households in each family, members of each household in each family. There was the proper swearing-in of Mr. Summers by the postmaster, as the official of the lottery.”

In the first round, a member of each family must draw a slip of paper from the black box and the one who picks the slip with the black spot—his/her family enters the final round. The master of the Lottery hurries them: “Guess we better get this over with…so we can go back to work.” Bill Hutchinson picks the marked slip and his wife Tessie, who was excited about the event till then, objects, “It’s not fair,” she says. But no one is listening as the next process is in place and now each member of the Hutchinson family must pick a new slip and Tessie draws the slip with the black spot. As the crowd rushes to stone Tessie, her little son is handed a stone too.

If one can make any distinctions between different kinds of lynchings, then this one is different from the lynchings by our honorable gau rakshaks or the lynchings of African Americans in North America in the last century—it’s a fertility rite that the folks in that fictional town believed would fetch them a bumper crop. But the mobs, their actions and their ambitions are similar in their cold brutality. In 1969, The Lottery was adapted into a short film, which strangely comes with a disclaimer—“The following is fiction”—as if viewers would think otherwise, and in 1996, a full-length feature film that goes by the same name was released.

The etymology of the word ‘lynch’ that we toss about, each time gau rakshaks bludgeon a man to death with sticks, is a western import that can be traced to two men in 18th century North America: Charles Lynch and William Lynch. It’s assumed that one of these two men, or perhaps both of them, lent their name to the act. They headed extra judicial courts during the American Revolution, rounded up loyalists to the British throne and had them lynched.This came to be widely referred to as the Lynch Laws and the word ‘lynch’ with its violent connotations entered mainstream vocabulary.

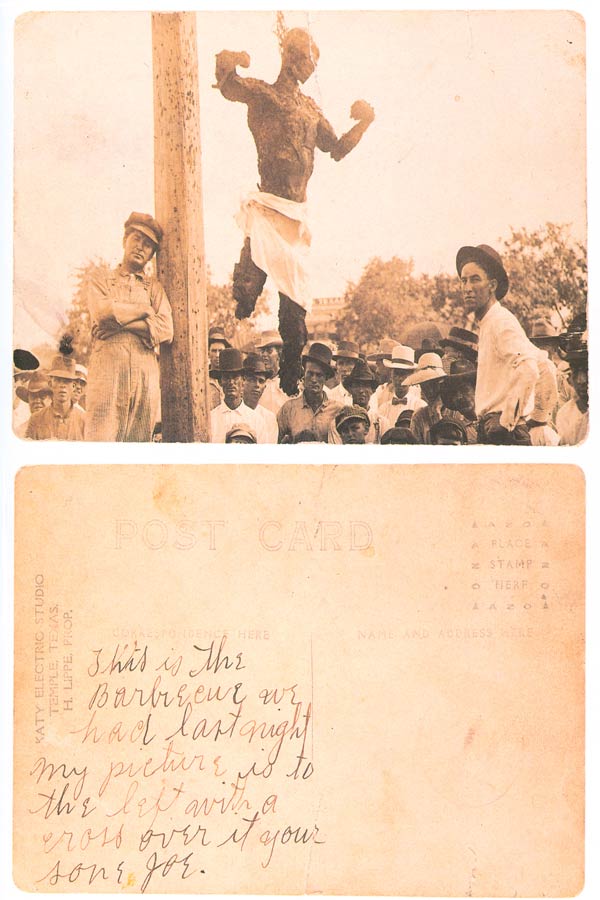

But, it was in the fag end of the 19th century and well into the first half of the next century that this particular form of butchery bloodied the supremacist landscape of America. As African-Americans came out of slavery and began to enjoy their civil rights, nearly 4000 of them were lynched by racist mobs in a span of 50 years.

Besides the videos on social media and an odd documentary, there is little serious study on mob behavior of our honorable gau rakshaks in India. Artistic and creative work that shock our imagination and force us to remember is miniscule—none actually. We must turn to sociologists and psycho analysts to understand the character of these lynch mobs and the banality of evil.

According to Sigmund Freud, the mob is a different species which knows neither shame nor fear and acts quite differently from the individual self. Drawing from Gustave Le Bon’s The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind, Freud explains, that in the mass (read mob/crowd) the uniqueness of the individual disappears as he joins the crowd and, by the sheer force of its numbers a “sentiment of invincible power” overwhelms him. And this, according to Freud, allows him to yield to instincts which he would have normally kept under restraint, “he will be less disposed to check himself from the consideration that, a crowd being anonymous and in consequence irresponsible….”

Interestingly, the gau rakshak mob too adopts a herd mentality and Ashis Nandy, writing in India Today, points out that the brutality is even more extreme when “the ‘other’ is interjected within you, as a part of yourself, an intimate enemy, whom you are also fighting. You feel constantly contaminated by them, almost a form of possession that you have to exorcise. Because of that inner push, these lynchings are doubly aggressive.”

Though the first lynching, under the present government, that of Mohammed Aklaq (for purportedly storing beef in the refrigerator) happened in 2015, there is no clear data as to how many people have been lynched since then—for the national crimes records bureau statistics clubs all death by crime under one head. A Business Standard report gives you a fair idea on how cumbersome it’s for NGO India Spend to gather information on lynching in the name of cows. With lack of government data, they rely heavily on media reports. They have pegged the number of cow-related lynchings from 2014 to 2017 at 28. And others documenting the lynchings have bumped up the figures to 47 till date.

The recent acquittal of six accused in the lynching of Pehlu Khan (lynched while transporting cows) by a Rajasthan court, in spite of ocular evidence and a dying declaration, has shocked the nation as much as the crime. With the police conveniently fudging records on lynch mobs, courts shrugging off cases citing lack of evidence, state governments unwilling to enact anti-lynching laws, and bellicose television channels controlling the narrative—all obliquely justifying the actions of the gau rakshaks, it’s up to civil society, artists, singers and filmmakers to counter that narrative and seize the space. And it needs to be done now. In the last four years post Aklaq, no major film, song or art work has been done on this macabre theme.

Here we can draw inspiration from African-American literature and cinema which has tried to record the lynchings during the turn of the last century. Both documentary and feature films capture well the crimes of that dark period. The films were being made even as the haunting spectacle of lynchings dotted America.Though there were a couple of films on lynching by white directors at the beginning of 20th century, Within our Gates, a 1919 silent film, directed by Oscar Micheaux, is the first by an African-American which dealt with lynchings and racial tensions. It was preceded by a play called Rachel written by Angelina Weld Grimke, a biracial woman.

The theme caught the popular imagination—poetry, literature and music emanated from it. Strange Fruit, written as poem by writer-teacher Abel Meeropol in 1937, after he saw a photograph of a lynching, has seen different renditions of it by over three dozen singers down the years. First sung in the jazz style by Billie Holiday in 1939, singers like Nina Simone, Sting etc. lent their voice to it and was set to reggae by the pop group UB 40 in 1985.

“The bulgin’ eyes and the twisted mouth/ scent of magnolias sweet and fresh/ Then the sudden smell of burnin’ flesh” could easily be transposed on to the Indian landscape “bloodied bodies and broken bones/ scent of sour mangoes and sweet/ howls of horror and eyeless hollowed heads” but we hear no songs reigning our air waves forcing us out of our apathy.

Here and there, are solitary brave voices like Shabika Abbas Naqvi, a performative protest artist, who poetically gives voice to her fears. Shariqa Nida’s evocative poem in a blog giotelengana goes thus:

And now it seems that lynching speaks,

More than most speeches do,

About the country’s future and security,

And of people’s rights and privileges too.

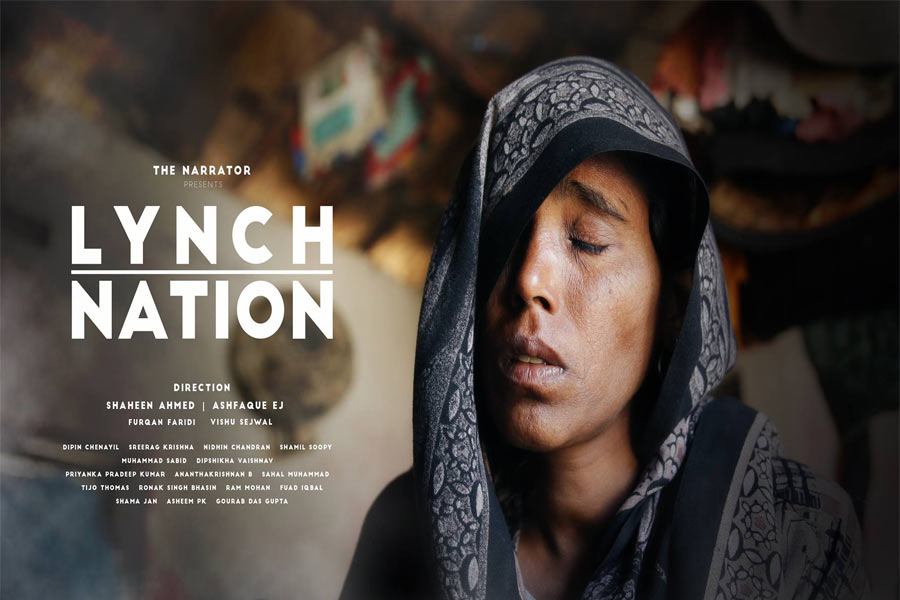

The documentary Lynch Nation directed by Shaheen Ahmed and Ashfaque E J of the lynching of Muslims and Dalits is aired only at select private screenings since it has no CBFC certification. What’s strange is that the government wants to pull even the trailer of Lynch Nation off YouTube, according to a report in The Print. The Guardian documentary, beyond the long arm of the Indian government, shows the lack of remorse among the cow protectors and attempts to normalize lynching, “this is not violence,” says one of them and, the BJP leader, Gyandev Ahuja, at a rally calls for the beheading of heathens.

The documentary Lynch Nation directed by Shaheen Ahmed and Ashfaque E J of the lynching of Muslims and Dalits is aired only at select private screenings since it has no CBFC certification. What’s strange is that the government wants to pull even the trailer of Lynch Nation off YouTube, according to a report in The Print. The Guardian documentary, beyond the long arm of the Indian government, shows the lack of remorse among the cow protectors and attempts to normalize lynching, “this is not violence,” says one of them and, the BJP leader, Gyandev Ahuja, at a rally calls for the beheading of heathens.

This barbaric purification rite which seems to have the sanction of political parties is a way of religious and social control to keep the Dalits, Muslims and other minorities in check. It is no longer enough to write forgettable letters to the PM—our artists and writers should not fail us in this lynching hour: our air waves, our cinemas, our artscapes should fill with stories of these grisly crimes till their horrors seep into our cells and memory and take residence there stirring our conscience to bring it to a halt.

What Albert Camus writes in Reflections On The Guillotine is relevant to lynching too: The survival of such a primitive rite has been made possible among us only by the thoughtlessness or ignorance of the public, which reacts only with the ceremonial phrases that have been drilled into it. When the imagination sleeps, words are emptied of their meaning: a deaf population absent-mindedly registers the condemnation of man.”And like he suggests, perhaps if people touch the implements of cruelty and are made aware of the agonizingly slow death that takes hours and sometimes days, “then public imagination, suddenly awakened,” and nauseous, will reject this violent blot on their conscience. After all, as our leaders say: it’s not in our culture to kill.

Cover Image: Buffaloes at Pehlu Khan’s home in Mewat; Pic: Anand Kochukudy