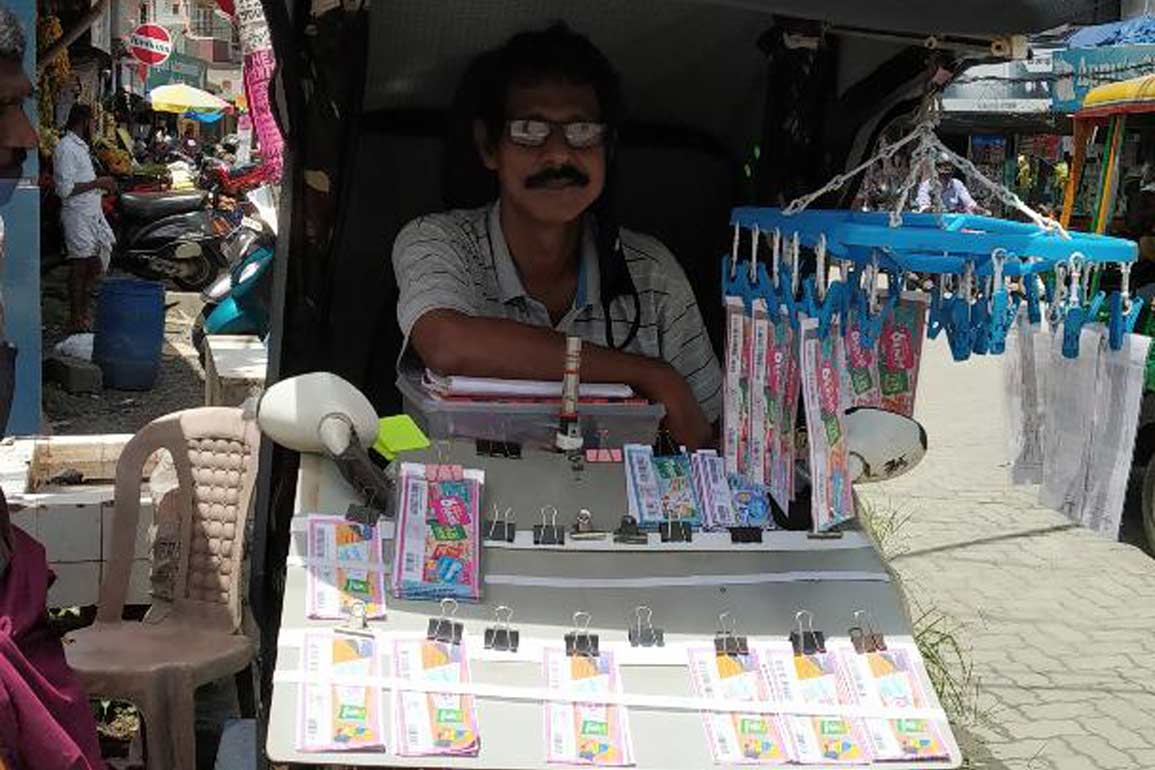

On most mornings, I stop at a cart that sells green coconuts at Palarivattom Junction in Kochi, so I can have its cooling water. Less than two feet away, there is a three-wheeler with a hood. A man with his paralysed legs placed on two pedals in front of him sells lottery tickets. I have rarely spoken to him except to buy tickets a few times.

One afternoon, when I went to have the water, the lottery-seller was not there. It seemed so unusual that I asked the coconut seller what had happened.

“Oh, Anto goes home in the afternoons, and returns in the evening,” he said. Then he told me about Anto’s life. I had assumed Anto had been afflicted with polio from his birth but that was not true.

So, one afternoon, I went to Anto’s house to hear his story.

On March 26, 1999, Anto had been called to unload advertising boards from a van at a godown in Edapally. Only he and the driver were present. Because of the weight of the boards, the vehicle could not go up an incline near the godown. So, it was parked on the slope. The driver got down to open the shutter at the back, as Anto stood to one side. Unfortunately, the vehicle started rolling back. The driver jumped out of the way, but the van toppled sideways and fell on Anto.

He started screaming. Several bystanders rushed up and with a collective shouting and exhalations of breath, and using their shoulders and hands, they pushed the vehicle back on its wheels. Anto was taken in an autorickshaw to the Ernakulam Medical Centre. There, the doctor told him that his spine had been broken. An operation was done, to join the cords, so that Anto could at least sit up.

But nothing else could be done. Anto lost movement of his legs and all physical awareness from his waist downwards. Thereafter, he did physiotherapy for several months. Thanks to the third party insurance of the vehicle, he had got a payment of Rs 2 lakh. He tried to walk, using a walker. But there was not much of an improvement. Anto felt depressed. He gave up and spent a few years lying on his bed. But, by then, he was staring at a financial crisis.

One day, a friend suggested to Anto that he could earn money by selling lottery tickets. His two daughters pushed the wheelchair to the main road, on Thammanan, one kilometre away. “I sold tickets for one year,” says Anto. Then a reporter of The New Indian Express noticed Anto while riding past on his bike. Later, he published a feature on the paraplegic in 2011. Consequently, The Hotel and Bar Association gave Anto a donation of Rs 40,000. The Cochin Corporation followed it up by providing a scooter. Thereafter, Anto went to the main junction at Palarivattom in 2012 and started selling tickets.

He has been there ever since.

Anto gets up at 5 am and after a cup of tea, he gets ready and reaches the junction at 6 am. At 10 am, one of his daughters brings breakfast in a tiffin box. At 3.30 pm, he rides back home and has lunch. Then at 5 pm, he returns to the junction and works till 10.30 pm. That’s 15 hours at the junction every day. And there are no holidays. On average, Anto sells 200 tickets a day. “But now there are many sellers, so the numbers are going down,” he says. “Another problem is that the minimum rate of a ticket has gone up from Rs 30 to Rs 40. So, sales have gone down. And because of the coronavirus, it has become much worse.”

Anto is honest enough to say that nobody has won a bumper lottery prize from his stand. But there have been many winners of a lower denomination, from Rs 100 to Rs 5000. From unsold tickets, Anto has sometimes won Rs 500 or so.

Many people buy tickets, but the buyers are mostly males. “There are a few who when they see that I am handicapped who buy a ticket out of sympathy,” says Anto.

It is not an easy job. Sometimes, buyers will scrape away part of the number. They can change the number zero into a three. The number six can be made into an eight. Then they will show it to Anto and say they have won a prize. “They do it so well, it is difficult to spot the fraud,” says Anto. “I end up paying them the money. But at the lottery office, they will tell me I have been tricked.”

Some customers will come in the night and say they have a bus or train to catch. And they will hurry Anto to pay the money. Nowadays, Anto scans the number with his mobile and checks it with the lottery office by sending it on WhatsApp.

Some people have taken loans from Anto. One day, a middle-aged man said, “My car has a puncture. I have to change the tube, but I don’t have any money.” Anto had seen him around the junction and so he gave him Rs 500. After that, he never saw the man again. Another man came and said his mother was in the hospital and he needed some money to pay for the bill. So Anto gave it to him, but he vanished after that.

But Anto is at his post all the time. He says that the summers and the monsoons are difficult. In the summer, because of the heat, it can become unbearable. “I don’t have a fan,” he says. “The charge of the vehicle’s battery will go down if I connect it to the fan. And when it rains, I don’t move. I stay right there.”

To lessen the pressure on his back, he sits on a tube. Because of long hours, sores develop at the back of his legs. Anto stays at a house that he has built by taking a bank loan.

Anto married Daisy in 1992. His elder daughter, Delshy, 25, who has a Masters in Business Administration degree, works in an office. His other daughter, Delmy, 23, took a bank loan and is doing a finance course in Berlin, but is stuck in the German city because of the lockdown.

Daisy says that Anto likes to work a lot. “He always felt happy working,” she says. “Anto had been depressed for many years, but selling lottery tickets keeps him occupied.”

Asked whether he is angry with God over his misfortune, Anto says, “This is fate. Accidents happen.”