After my birth on September 17, 1926, my mother became very sick and her sister Mariakutty looked after me. This sister lost her husband very early in her marriage and had no children. Frankly, I have no recollection of those days until I started my schooling.

I had my primary education at the Kurumpanadam parish school, near Changanacherry. I have faded remembrances of those days, except to say that the headmaster at that time was one ‘Kakkallan Sir’—a strict man. Most of the students were scared of him. Then I remember Antony Sir. He was very quiet and friendly.

My high school studies were at St. Berchmans. After I passed out I joined the first batch of Sacred Heart College, Ernakulam in 1944. My sojourn at Thevara was short-lived, as I was expelled from the college for participating in a demonstration against Sir C P Ramaswamy Iyer, the then Diwan of Travancore, who was harassing the freedom fighters. He had come to Thevara to inaugurate an Anglo-Indian school. The hostel students decided this function had to be stopped to demonstrate their animosity towards the Diwan. The function was held near the Perumanur railway line. The meeting was disrupted when several students threw stones from vantage points of the railway track. Sir C P left in a hurry for Trivandrum.

Meanwhile, Dixon, the Diwan of Cochin, felt the action of the students was unpardonable and ordered the expulsion of the ‘culprits’. Thus, in the middle of the academic year, 12 students, including myself, were issued Transfer Certificates to seek admission in any other college. Because of this background, no colleges would have accepted our TC and so, a friend, Jacob Thelly, suggested that I go to Calcutta.

He told me I could meet ‘Shirman’, an airport security officer stationed at Calcutta, who had come to Cochin for a vacation. This meeting was helpful in many ways. He allowed me to travel with him when he returned to Calcutta. This was in the year 1947. We travelled in first-class and its luxury was a revelation. The day we arrived at Howrah station, curfew was in force. This was because of the communal riots prevailing in the city. Somehow, we managed to reach his residence and he accommodated me in the flat. I stayed with him for a few weeks until I managed to move out to a bachelor’s flat. I was 20 years old then.

Calcutta was a big city, especially for a young college student who had left Kerala for the first time. The size, the crowds, the buildings—it was a spectacular vision of the new world, the second biggest city in the British Empire. Soon, I got admission at Ashutosh College for B Com. Joining the college was easy. Earlier, I had made inquiries at St Xavier’s College and discovered that the hostel fees were high. So, I decided to stay outside and joined the night classes at Ashutosh College (6.30 to 9.30 pm), so that I could work during the day and study at night. At that time, contact with home was only through letters.

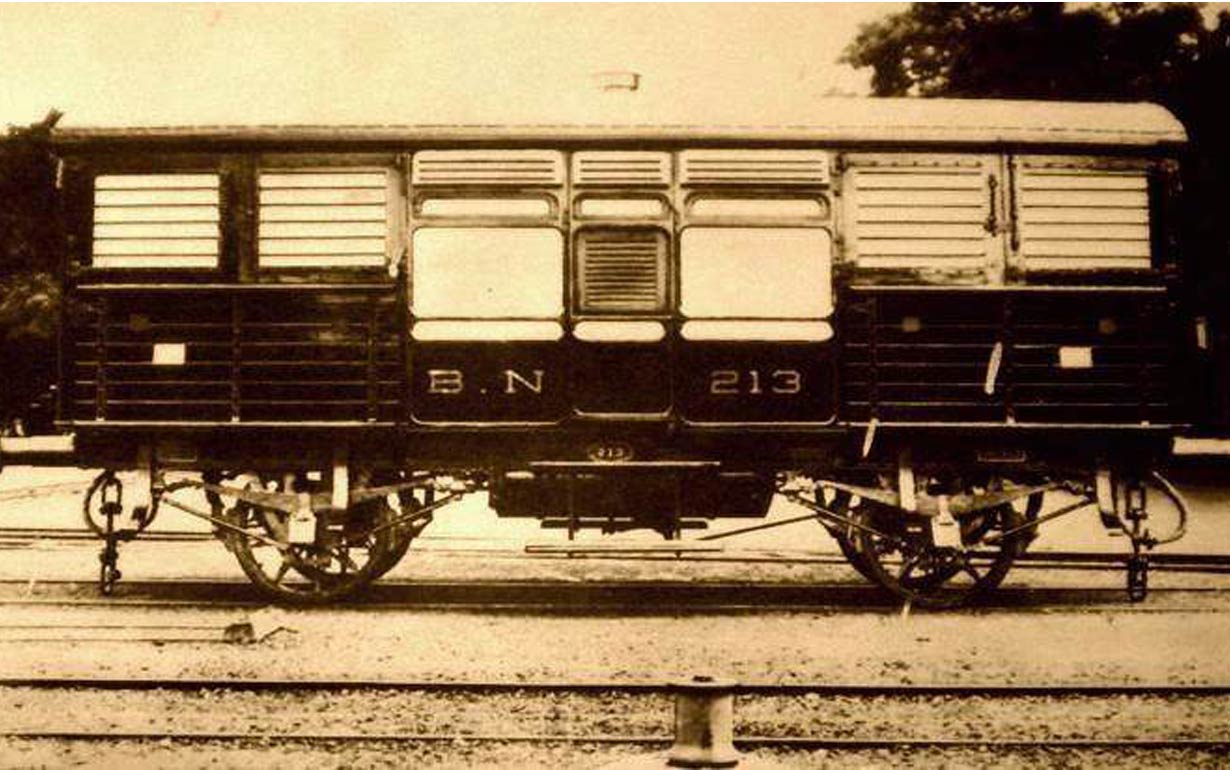

I was able to get a job also with convenient timings for office work and college. Within a year, I managed to get an opening with the Bengal Nagpur Railways at Garden Reach. This opened up further opportunities in studies, as the timings were most suitable. So, after my graduation, I joined the University Law College for LLB, which I completed in 1951. So, with the B Com LLB, I had further opportunities and an English company, Hoare Miller, appointed me in its sales department. I was lucky to have an understanding Englishman, Mr Ridley, as my boss. Slowly, life changed.

This job involved a lot of travel all over India and for twenty days of the month, I was travelling. I managed to get bulk orders for the company and was able to get distributorship for rubber latex from the Cochin-based Pierce Leslie and Company Ltd. This agency enabled the company to have a good turnover. I received an increase in remuneration, apart from a commission on sales. This continued for eight years and I had a car and driver allotted to me by the company.

All good things cannot last. The European management sold the company to a Marwari. Thus started the ordeal for the division I was heading and for me. My division was manufacturing mattresses, bus seats, cushions from coir fibre, as well as imported processed animal hair. Our division was the pioneer at that time. All operations were done manually, and more than 300 workers were employed at the factory on 35 Diamond Harbour Road. The new management allowed us to continue for over five years and then decided to close down. I was instructed to negotiate with the CPI union and given the option to quote liberal terms. The statutory provision for closure was half a month’s salary for each completed year of service. This was increased to two months for each completed year of service—four times the legal entitlement. The union accepted the terms and the factory was closed without any ‘bloodshed’. Within three months I was served with a termination notice, paying only what was agreed upon in the contract – three months salary as notice period on either side. At that time, as a covenanted officer, I was not allowed to join any union.

My marriage

I was told by my father, P J Sebastian, to go to Ernakulam to Justice Joseph Vithayathil’s house to meet a girl. My father accompanied me. At that time, there was a house blessing function and so, the meeting with the girl was a casual affair. We met in the presence of many.

Ritty was wearing a saree but to me, she was a small girl, not mature enough to be a wife. She was shy and we exchanged a few monosyllables. So, the parents decided that we are ‘made for each other’ and the marriage was fixed. It took place on December 30, 1954, at Holy Magi Church, Muvattupuzha and was blessed by Monsignor Nambiaparambil, in the presence of Ritty’s uncle, Fr Mathew Vadakel. The reception was at Vadakel House, where a ‘pandal’ was raised. There was a good crowd at the reception.

Settling down in Calcutta

I had to leave for Calcutta soon after the wedding to make arrangements to get a new flat and Ritty remained behind with my parents at their home in Nadekepaddam, (10 km from Changanacherry). In due course, I escorted Ritty to Calcutta. We stayed at 48 Diamond Harbour Road with my cousin Xavier Thomas and Susy.

We had a fairly large flat with three rooms and a covered verandah in the back, which we used as the dining room. We had a domestic help, Chacko, who had come from my parents’ home. This combined staying did not last long and Xavier took a flat closer to the St. Ignatius Church and moved out.

We always had someone from our family with us. Ritty’s brothers, Babu and Mathew Vadakel, my nephew, Sony Kurien, and brother-in-law, Dr. Joseph Thayil… all of them stayed with us one after the other. I lost my job when my children were still in school. The days were hard, as both had to be taken to school and collected in the afternoon. So, I bought a car, and a driver, who worked with me at Hoare Miller, joined me.

The loss of the job was a critical blow. However, with God’s blessings, we could start a small factory, situated at Liluah, Howrah, producing the same products we were making in Hoare Miller. We were able to pick up a few of the workers also and thus was born Comfort Mattress Manufacturing Company with the office at 56, Shakespeare Sarani. George Thomas, a former salesman of Hoare Miller, joined me. The office was very close to the residence. The schools were also nearby. We had all the former customers and it was not a ‘hard’ beginning, though there was a shortage of ‘capital’, especially to procure raw materials.

Within a year, the situation eased up, and from then onwards, there was no looking back. The visit to the factory from Park Circus was an ordeal, especially when there were traffic jams on Howrah Bridge. We had no other option but to continue till such time we decided to close the unit. We had agreed to hand over the factory to the workers on the condition that we will buy the entire production. This arrangement continued for a few years and eventually, we had to discontinue this.

Side by side with the factory activities, we had developed the sale of foam mattresses and rubber latex. The foam mattress agency was managed by George and I had the latex sales. This continued to develop well and those days were quite happy ones. I was able to buy cars according to the need of the times—we would visit Kerala once in 15 to 18 months. With my father’s demise in 1972, the situation changed. With Amma alone, I knew I could not continue in Calcutta for long. I felt the best way was for Ritty to return to Kerala. She left Calcutta in 1983.

Social work

During the first 25 years in Calcutta, I was attached to the St. Ignatius Church on Ekbalpore Road. On Sundays, I saw a group of people gathering at the Presbytery. Out of curiosity I made enquiries and was introduced to the work of the St. Vincent de Paul Society (SVP). This apostolate was run by laymen and women. The only qualification to become a member was the willingness to sacrifice some time in a week for your neighbour in need.

My association with the SVP now is more than 60 years. Joining the St Ignatius Conference in 1948 as an ordinary member, I could reach the top as National Vice President. This association and my experience over several years exposed me to the plight of the poor and the needy. I have seen life in all its aspects and understood the meaning of love and concern for the less fortunate.

Later, landmark decisions by the National Council had widened the participation, which has resulted in more members from all over India joining the Council. In my humble way, I did what I could, within the limits of my time and money, by continuing in the society as National Vice President for over 20 years and as President of the Central Council of Calcutta.

The turning points in my life

The decision to go to Calcutta, after the expulsion from Sacred Heart College, turned the tides of my life. Yet another turning point was the loss of the job with Hoare Miller and the challenging decision to continue in Calcutta and face the realities of life.

As for the question of whether I regret the decision of going to Calcutta, certainly not. In Calcutta, we roughed it up, enjoyed the fruits of our labour and had the mental satisfaction of achieving our daily bread without much outside help.Calcutta is a city with a very big heart, embracing the thousands pouring into the city daily. All of them loot the city without doing anything for the city in return – one-way traffic.

Philosophy of life

A simple man, without much expectations to achieve anything. Be humble and practise humility in all aspects. “The least among all of you is the greatest” (Luke 9:48)

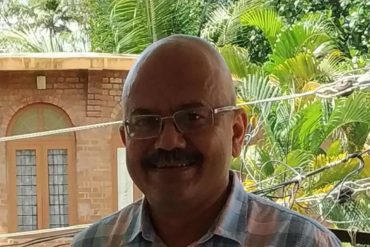

(Joseph Sebastian is now living a retired life in Kochi)

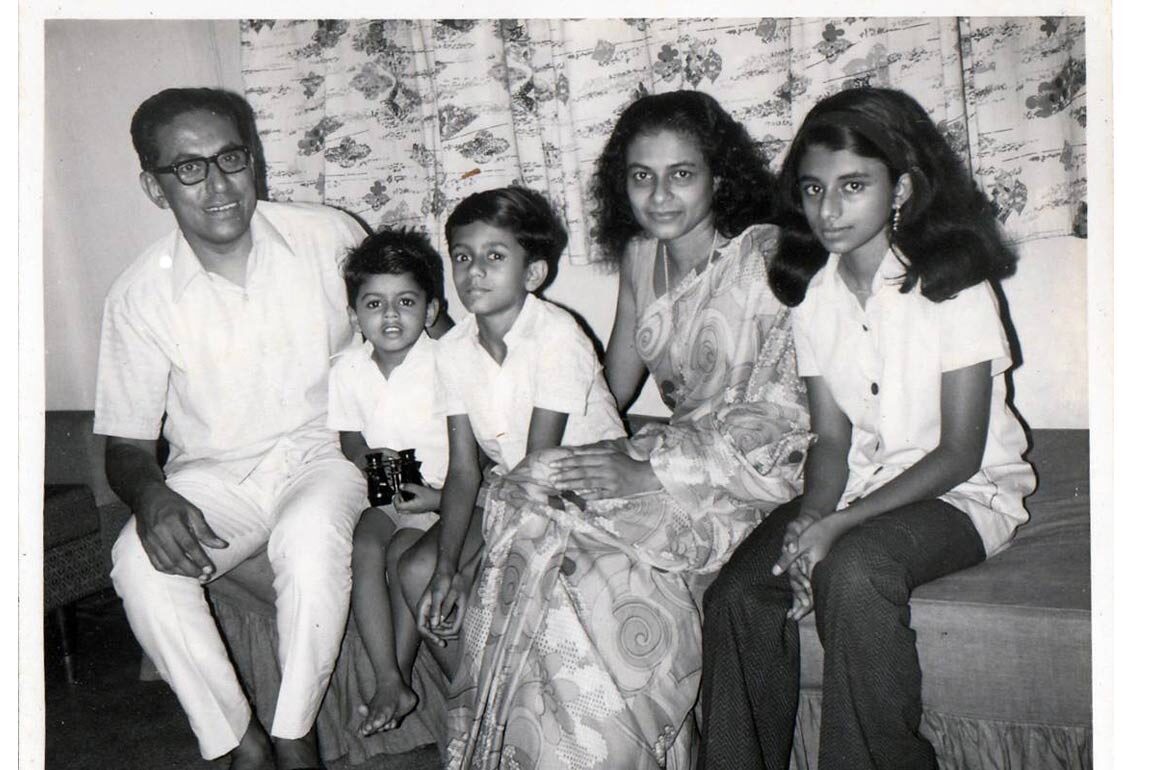

Cover image:Joseph Sebastian and his family in the 1970s