On most days, at 1 p.m., my colleague Mark Peters would come up from the circulation department on the ground floor to the editorial section on the first floor of our newspaper office in Kochi and beckon to me. Then we would go to the canteen to have lunch. And our conversations could be on politics, human relationships, marriage, history, psychology, media and women. Most of the time I listened, because Mark was a natural raconteur. Since both of us grew outside Kerala, there was an easy camaraderie.

Mark had this extraordinary gift of being friends with everybody in the office. From the boss to the peon and the security guards. And in Fort Kochi where he stayed, this Tuticorin-born Anglo Indian would talk with the stationery shop owner, the fisherman, the bus conductor, homestay owners and strangers.

Once when he went to the post office, he saw a foreigner. Mark introduced himself in his impeccable English. It turned out that the man was a top shot at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) at Washington. Many big guns would roam around Fort Kochi, revelling in their anonymity and the unique charm of the town. But if Mark came across them, be it man or woman, he would unlock their identity.

And then he would make a call… to me.

“Hi, I’ve got a good story for you,” he would say.

And he was right. It would always be an interesting person to meet and do a story.

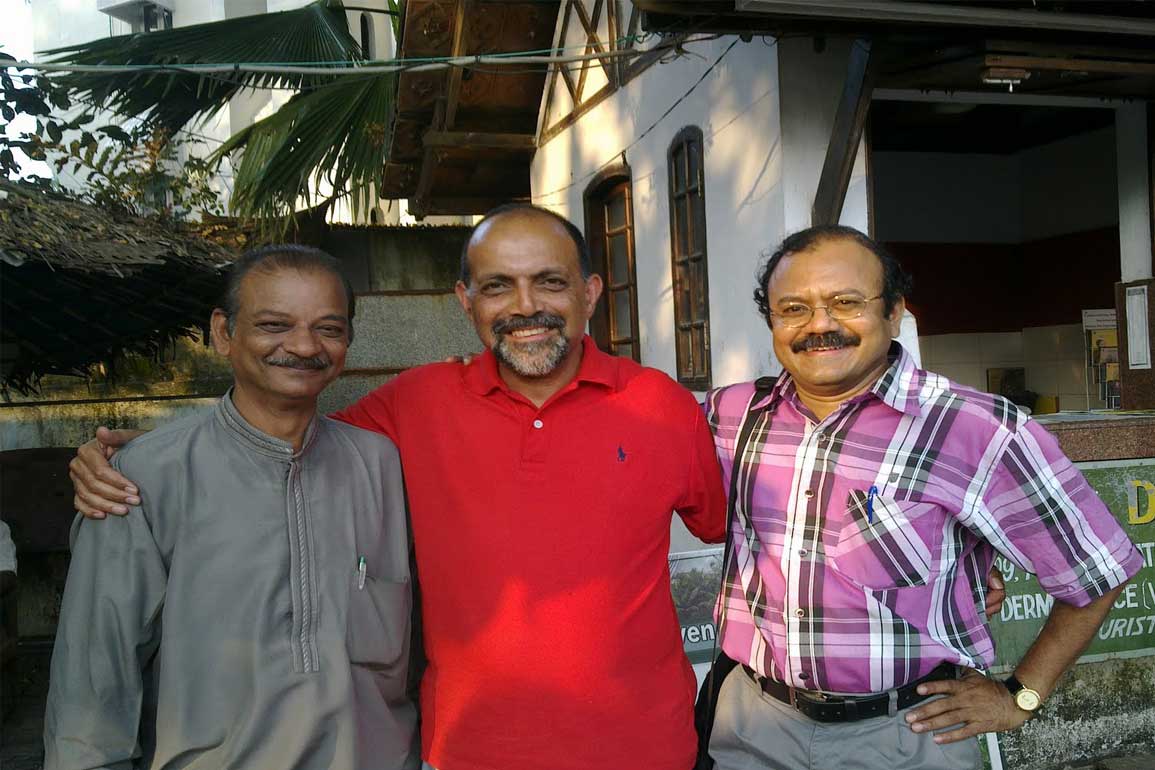

I remember Mark telling me, in December, 2011, of a South African journalist, Mansoor Jaffer, who had come to India, along with his wife, Kay, in search of his Indian roots in Maharashtra. But their first stop was Fort Kochi. And I met him and did a story. Kay took a picture of the three of us together and that is the only photo in which Mark and I are in the same frame.

Mark was a fount of story ideas and had an unerring instinct of what would make an interesting story. Once I told Mark he could have been such an excellent journalist. He smiled enigmatically.

Sometimes, a story idea would come accidentally to Mark. Once, near the headquarters of the Reserve Bank of India, at Kochi, he was crossing the busy road when a bus speeded up. So, he was stranded in the middle next to the female traffic warden. So, he started chatting with her.

When he came for lunch, he told me about Sajitha.

“It’s an excellent story,” he said.

“Are you sure?” I said.

“I am,” he said.

So I met her. And Mark turned out to be right. It was an interesting story. Sajitha told me of a man who had an epileptic fit on the road right in front of the traffic. Blood and water dribbled out of his mouth. She stopped the vehicles, with an upraised palm, and placed her watch on his palm. She remembered the touch of metal helped to control a fit. Then, with the help of bystanders, Sajitha put him in an autorickshaw and took him to the Lisie Hospital. By then, the man had become unconscious. She took his mobile, called a random number, and it turned out to be a friend. That friend informed the family members. Soon, they arrived at the hospital. One week later, the grateful man came to the crossing and presented Sajitha with a gift. “You saved my life,” he said, with a smile. When the article appeared, she received a lot of kudos. Sajitha thanked Mark for organising the coverage. And I thanked Mark for the idea.

Mark left the office in 2014. But we remained in touch. I would go across to Fort Kochi and have lunch or tea with him. Since the Kochi Muziris Biennale was held in Fort Kochi, as a feature writer, I went often to the venues. So, there was always a chance to meet Mark.

Then one day, one-and-a-half years ago, he called me and said, “I have grave news.”

“What is it?” I said.

“I have been diagnosed with colon cancer,” he said. “Stage 4.”

The moment I heard Stage 4, I became silent for a few moments. Stage 4 is too late. My father-in-law died of pancreatic cancer. He was in Stage 4 when it was discovered. Later, I spoke to a doctor who was a top-notch gastroenterologist. He said Stage 4 in the colon was bad news.

Mark went through several rounds of chemotherapy followed by exhaustion, loss of appetite and weight. But through all this, his voice and his thinking remained crystal clear. To raise his spirits, I would crack a raunchy joke. He laughed easily. It reminded him of delightful times—of Christmas lunches with his family and New Year’s Eve parties at the Anglo-Indian Club.

But the odds were stacked against him. For a while, the cancer was in remission. Then it returned with increased force.

Once when I called him, he said, “It’s all over the place …. lungs, liver.” Then his voice trailed off.

And in the past two months, Mark declined. He knew that he was going. And he felt sad that he could not see all his children: while one son remained in Fort Kochi, two sons and a daughter lived in Dubai.

His wife Evelyn told me that Mark would always ask when the lockdown would end, so he could see his children for the last time. Sadly, the lockdown did not end.

On the morning of May 18, I called Mark. He said, “Shevlin,” and couldn’t speak further. All I heard was laboured breathing. Evelyn took the phone and said, “Mark is unable to speak.”

At 8.30 p.m., Mark complained of breathlessness. Evelyn took him to Lisie Hospital. He was put on a ventilator. But the doctor warned her that Mark could not take in the oxygen much. He said he may live for a day or two. But it did not take that long. By 11.45 p.m., Mark breathed his last. My wonderful friend and a fount of ideas was no more.

Since it was not unexpected, it was not a shock. But a weight descended on my heart. I felt impoverished. The only thing that matters in life is relationships. All the rest, like fame, money, position and power are ephemeral. People remember how you behaved, not what you achieved.

At the cemetery, as I waited for the body to arrive, I overheard people say, “Mark was a gracious man.” “He was a wonderful friend of mine.” “Mark was always well-dressed, polite and with a smile on his face.”

Then the coffin arrived in an ambulance. Mourners held the hooks at the side and carried the coffin to the cemetery. The lid was removed. Mark had been swathed in white. He had white gloves with a black rosary between his fingers. A small wooden crucifix had been placed on his chest. And cream flower petals lay strewn along the length of the body. The priest said the prayers. There were fewer people around, because of the lockdown restrictions. There were trees in different areas. But where Mark was being buried, it was in the sunlight.

The coffin was laid to rest. Family members and friends threw in white flowers. It fell softly on the lid. And as the gravedigger filled up the grave with mud, Evelyn looked at her Dubai-based children, who were watching the event on a live stream, and said, “Daddy is gone…. forever.” Yes, Mark has gone physically but he will always remain in my heart. And in the hearts of those who loved him.

And as I was returning home, I thought to myself, ‘I won’t be surprised if Mark, somewhere in the Universe, will continue to pop story ideas in my subconscious when I am fast asleep at night.’