If only Leonardo da Vinci had the habit of signing his paintings, the world would have been less vexed. As the biggest retrospective of his works which opened in the Louvre, Paris, to mark the 500th birthday of Leonardo last month (on till March next year, so hurry up), there is continuing debate about the veracity of some of his paintings. The Louvre retrospective is the largest collection of the Italian maestro’s works which showcases 160 of his works—paintings, sketches, notes.

Leonardo died on May 2, 1519 at the age of 67 in a house provided by King Francis I. He was the court painter at the King’s palace. Among the things found in his room, after his death, was the rolled up Mona Lisa (portrait of Lisa Gherardini, wife of Florentine trader, Francesco del Giocondo), on which, he is said, to have worked on for several years. He had worked on it for 4 years in Milan but did not deliver it to the man who commissioned it. Instead, he carried it with him to France. The slowness with which Leonardo worked was proverbial and he further added layers, shades and more meanings.

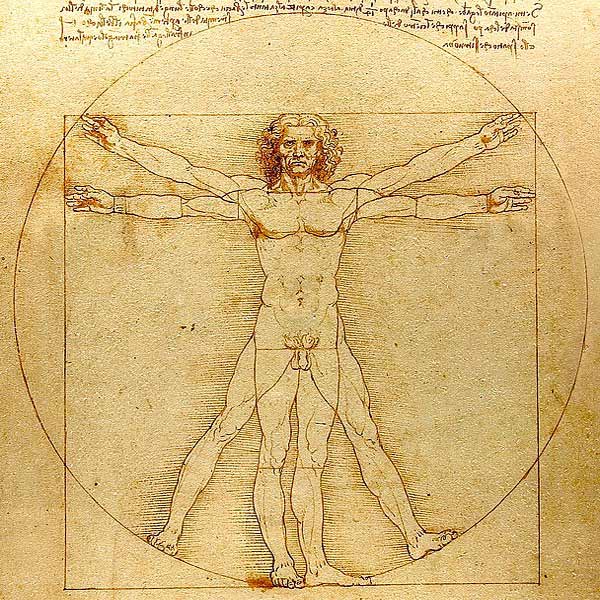

Leonardo made matters more difficult by always writing in mirror image and that too from, right to left. Although solving that isn’t much of a problem, but since he located himself in the hazy space between science and art, he neither afforded us an easy analysis of his works, nor left us any clues as to what he was searching for. What was he journeying for? Painting for him was a distraction from his larger obsession with irrigation projects, the meaning of the universe itself, the movement, motion of water (of which he left many sketches), his botanical drawings and the human anatomy on which he spent many hours dissecting bodies and then sketching the tendons, nerves and muscles and also such notions that a circle is made up of smaller squares.

In the Louvre exhibition, fully booked for the next month, there are 160 works including the Vitruvian Man which being extremely fragile got an Italian court sanction only days before the exhibition opened in October. There is a virtual reality tour of all his works which is as exhilarating as the real paintings on view. However, missing is Salvator Mundi (Saviour of the World) whose ownership is known but none of the Middle Eastern monarchs who either share the ownership or know about the $450 million painting did reply to the repeated requests of the show’s curators Vincent Delieuvin and Louis Frank.

Last reported, Mundi is believed to be kept inside the yacht of Saudi King Mohammed bin Salman who had put up the money. It was listed to be up for exhibition in Louvre Abu Dhabi last year, but there is no confirmation yet of the viewing. The other big Leonardo work, the Codex Leicester, which was his notebook, is now in the possession of Bill Gates. So, two of the world’s richest men have taken possession of two most invaluable works that the world may now not get to see.

What has come as sort of a blow to the Leonardo season is the unexpected attack launched last week on Mona Lisa by art critic Jason Farago who said in the New York Times that it is “handsome but only moderately interesting” and that the small painting is holding the Louvre to ransom with unmanageable crowds. “Content in the 20th century to be merely famous, she has become, in this age of mass tourism and digital narcissism, a black hole of anti-art which has turned the museum inside out,” Farago wrote. Drawn by Mona Lisa, 10 million visited the Louvre last year.

It is true that there is a sense of dejection or punctured expectation when viewing the Mona Lisa which has been given an entire room, as this writer felt while viewing it in June this year. But even for those who think it is anti-art there is enough of Leonardo’s paintings to be fascinated with.

The beautiful finger pointing to the heavens seen in Salvator Mundi is also seen in his St John the Baptist. Leonardo’s male figures including Christ as baby and as savior has an androgynous look. No wonder since Leonardo was sexually disinclined (according to Freud). The curly hair of baby Christ is clearly a copy of his long-time pupil Andrea Salai (Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno). Whatever your views, to be at Louvre to see The Vitruvian Man or Madonna of the Rocks or Saint John the Baptist is to see the mind and genius of the man who changed the world.

In 1550, Giorgio Vasari wrote of him thus: The greatest gifts are often seen, in the course of nature, rained by celestial influences on human creatures; and sometimes, in supernatural fashion, beauty, grace, and talent are united beyond measure in one single person, in a manner that to whatever such an one turns his attention, his every action is so divine, that, surpassing all other men, it makes itself clearly known as a thing bestowed by God (as it is), and not acquired by human art… In him was great bodily strength, joined to dexterity, with a spirit and courage ever royal and magnanimous; and the fame of his name so increased, that not only in his lifetime was he held in esteem, but his reputation became even greater among posterity after his death.