“When was the last time you saw such a headline?” R Rajagopal, editor of The Telegraph, asked a hall full of college students last month. “Let us see how the headline works here: first the sledgehammer blow. Then the tug at the heartstrings.”

As part of his guest address at St Berchmans College, Changanassery in Kerala, Rajagopal circulated copies of the front page of the last edition The Warroad Pioneer, the 121-year-old community paper of Minnesota that closed down recently, and asked the students to roll the headline off their tongues: Final Edition/How Lucky To Have Known Something So Hard To Say Goodbye To.

“No pronoun. No names at all. No places. No figures.… Great headlines transcend clerical details. They soar beyond time and geography,” announced the editor.

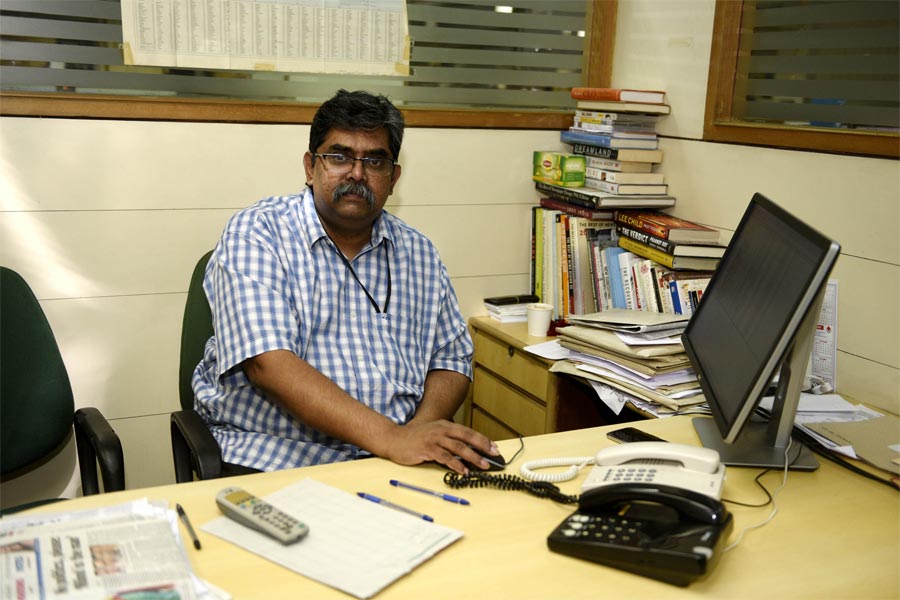

There could have been no better journalist than Rajagopal to lecture the students on headlines. It is the front-page headlines that have kept The Telegraph, the Kolkata-based daily that he helms, in the news. With most of mainstream media, especially television, giving in to toe the government line, The Telegraph is among the few to stand up to power and continues in its own spirited and irreverent way to question the government. Though published and circulated largely in the eastern part of the country, the paper’s digitised front pages and online news are eagerly awaited across the country, especially when there’s any major event or incident. The catchy, clever and sometimes shocking banner and screaming headlines are admired for their wit and courage.

Rajagopal was in the news recently for his exchange with Babul Supriyo, the Bharatiya Janata Party leader and union minister of state for environment, who had called him up seeking an “amicable apology” for an unflattering coverage of the September 19 fracas at Jadavpur University involving him and the students. The bone of contention was the screaming headline, “Babull at JU”. It was a pun on the idiom “bull in a china shop” and Supriyo was reportedly offended by it. Rajagopal told the minister that it could mean anyone since the line below spoke of “untamed protestors”. Rajagopal’s retort to Supriyo—“I am not a gentleman. I am a journalist”—was much quoted by the liberal press, which hailed him as a hero for keeping the resistance going.

Rajagopal is hardly happy. “A journalist should never make news,” he says at the beginning of the interview. “A journalist should report news and never become the news. Whenever it happens (unless it is about some big achievement) it means something is wrong with journalism.” Crediting the limelight to an unfortunate situation arising because most journalists do not do what they ought to, he feels there’s nothing to be proud of. “I have done nothing extraordinary; I am just doing my job.”

Rajagopal has been “just doing” his job for 30 years now. Having begun with the Malayalam daily Venad Pathrika in 1989, the 51-year-old editor worked with The Economic Times and Business Standard—where he often ended up doing political pages which was “unglamorous work” in pink papers—before joining The Telegraph in 1996. He captained the news operations at The Telegraph for more than a decade before he took over as editor in 2016.

The Thiruvananthapuram lad has lived in Delhi and Mumbai, but it is Kolkata—or Calcutta, as he calls the city in The Telegraph style—that he fell in love with because it is a “lot like Kerala”.

In an exclusive interview, Rajagopal speaks to The Kochi Post on journalism in the times of Babul Supriyo, The Telegraph’s front pages and, yes, the “Aunty-National” headline, why Kolkata is like Kerala and why you should not, or rather should, become a journalist:

Is this the first time in your 30-year career you got a call from a minister asking you to “amicably apologise”?

Yes. Nobody ever demanded an apology like that. We used to get calls from ministers and senior officers earlier too, mostly complaining about mistakes. It is not that we were always right. When we were wrong and they right, we have accepted their point and issued apologies. It is the standard practice; a minister doesn’t have to call. No one needs to call. A letter or email will do. If any mistake is brought to our notice, we take note. This case was different. The very language (“F***ing sold out.”) he used was uncalled for. Looks like it’s becoming normal now (to treat journalists like that).

Is this reflective of the state of media and press freedom in our country?

Yes, it is. It is now a cliché to say: “In the Emergency, they (journalists) were asked to bend and they crawled.” Now, they are doing so without even being asked. During the Emergency, there was a direct attack on civil rights and personal liberty. This is far worse. We just caved in without anyone having to lift a finger.

Is it too difficult to stand up to the government? What is the pressure like?

If you take a critical look at our work, something which some senior journalists have also pointed out, it is not that we are breaking too many stories. We are just holding up a mirror and reporting what we see and hear around us. It is not that we are digging out some hidden things. We are stating the obvious facts. Even so, we have to be constantly on our guard. We spend more time in fact-checking nowadays; fortunately, there are videos available. So, the earlier ploy of being “misquoted” or “quoted out of context” does not work anymore. But the fear of making a mistake is constant. Earlier, if we made a mistake, then we could make a correction and issue an apology. Nowadays, a single mistake can cost you heavily. So, what we used to check ten times earlier, we do 20 times now.

Why do you think journalists are afraid to stand up to the government? Far from opposing, they (mainly television media) do PR for the government.

I think most do it because they think this is what people want. Some of them claim to have the largest viewership. It’s like the movies, they want to give what they think the people want. If the ratings are authentic, it would appear that large sections of our country now like what is being dished out as news. It is as if our primordial instincts have been unleashed. I hope that it will run its course.

So, the buck stops with the readers and viewers?

Yes. The readers and viewers will have to decide what kind of media they want in this country.

Your front-page headlines and layouts are talk of the town. Every time there’s a major event or incident, The Telegraph front-page is most awaited. How do you produce them?

There’s a team (behind the frontpages). We work together. I listen to what everyone has to say. In the case of “Babull At JU” (Sept 20, 2019) there was a shortlist of seven headlines.

Speaking to People TV last year, you said “Aunty National” was one of your best headlines. Why is it so?

Yes, it was. It was a very good pun and very aptly conveyed the story.

It also attracted a lot of controversy, many found it sexist.

People said that we were profiling Smriti Irani by calling her “aunty”. That was not our idea. Context is very important here. It was during the middle of the JNU fracas, students were being beaten up on court premises and were sent to lock-ups; they were being picked up and arrested. All kinds of atrocities were happening on students. They are our future. In the middle of all this, the minister who is in charge of education stands up in Parliament to give a very nationalistic, jingoistic speech. She even said something like she will cut off her head (in her exchange with Mayawati). She was projecting herself as some kind of a big mother of nationalism. And she said that the slogan-shouting students were no children, suggesting that they had been mobilised against the State. Therefore, the headline. It (to make a sexist comment) was not our intention at all.

Do you have any personal favourite front-pages?

It’s difficult to choose. Every night when I put the paper to bed, I treat it like my final edition. We try to give our 100 per cent all the time.

Looking back, is there any headline or a front-page layout that you wish you had done differently.

Many. Like bad jokes, some headlines are too contrived or convoluted. Very few understand what they mean, which is unpardonable. If our readers cannot understand what we are trying to say, there is something wrong with the way we are saying it. We are trying to be more restrained these days, only for the sake of clarity. I remember once we said NASHUN. Some read it as Nashoon, Nass-Hun, Nash-UN, all of which are utter gibberish. It was my mistake. What we had meant was that while crying “Nation, Nation” the government was in fact shunning all responsibilities for a variety of transgressions that were listed below. Hence NASHUN, punning on the words “nation” and “shun”. Even now, I realise how complicated it was and how unfair it was to our readers. To my private delight, a Malayalam publication got the pun and wrote a small story on the headline.

Some critics say you tend to editorialise. Do you agree?

Say someone is lynched. When we say such a thing should not have happened, I think it is part of reporting. There’s a thin line between reporting and editorialising here. However, I must point out that we take care to avoid editorialisation in our news reports. We cover news, from multiple angles, reporting facts from the ground as they are. The culprit is the headline. I think newspapers should be given that leeway. Having said that, I do believe in taking a stand and our front-page headlines convey that.

Is that because you are opposed to the “rut of neutrality”?

Yes. Earlier it (neutrality) was a cherished value. But not anymore. We cannot afford to stay neutral in the current atmosphere. I personally believe neutrality is not something we should be aspiring for right now.

Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee is not known to be a champion of free speech? How is it bringing out a newspaper right under her nose?

I have never received a call from her or her people to put any kind of pressure on me. Before the 2016 Assembly elections, the newspaper I work for had taken a very aggressive position against many policies of the Mamata government and it is true that some politicians and citizens had filed cases against us. I don’t think there is anything wrong in aggrieved persons approaching courts. But look what is happening now, especially with the open letter to the PM.

There is a perception among a few that you go soft on Mamata Banerjee while being so vehemently opposed to Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

No, this is not true. Those who think we do not criticise her enough should check our coverage of her in the run up to the 2016 Assembly elections. We write against her whenever she gives an opportunity.

In your lecture to college students you said that the news gets compromised because it comes cheap, and that cover prices of newspapers should go up in order to make news more independent? Do you think Indian readers are ready to pay for news?

Some papers in south India have already raised their cover prices. It will be a controversial issue in India because we have a lot of poor people. It has to be done in a structured manner. What I feel is that there should be a conversation regarding it. So far nobody is talking about it, possibly, for the fear of circulation dropping. If this is the case it only shows how vulnerable journalism is.

There was a time when people would generally say that ABP (publishers of The Telegraph) was sarkari (punning on the Sarkars who own the company), meaning no one lost their jobs, just like in the government. But the company in 2017 shocked everyone with massive, across-the-board job cuts; some sacked employees even complained of raw deals.

It was a question of keeping the newspaper viable. The extreme decision (to terminate about 700 jobs) was taken when the company realised that it could not afford to bring out the paper without cutting costs. A newspaper that cannot stand on its own feet can never question anyone beyond a point.

Care was taken to give the best possible (severance) deal to the staff. I will be belittling my former colleagues if I say I could understand their pain and sense of betrayal. It will be of little consolation to them but I had personally chosen the names of journalists from the newspaper I work for and I tried as much as possible to list those who would find it less difficult to leave the city and find new jobs elsewhere. I can do little but to apologise to each and every one for my personal failure to protect their jobs.

The Telegraph and ABP News are both owned by ABP Pvt Ltd. However, the Hindi news channel is in complete contrast to the English newspaper. Last year, there were even some high-profile exits like those of Punya Prasun Bajpai, Milind Khandekar and Abhisar Sharma. Bajpai complained about the lack of editorial freedom. How do you coexist? How much editorial freedom do you enjoy to be able to do what they could not?

Television is a completely different subsidiary. Based in Delhi, ABP News is not only physically removed from us by the distance (The Telegraph is headquartered in Kolkata) but editorially also we are completely different entities. I don’t have a ready answer for that; all I can say is till date I have not faced any kind of interference in my work from the management side.

Publishers and managements often get the blame but rarely any credit when they stand by the journalism carried out by journalists. I could not have edited the paper the way I have without the support of the management.

These days, I constantly remind myself of an exchange between Ben Bradlee and Katharine Graham in the movie, The Post.

Bradlee: If we don’t hold them accountable, who will?

Graham: We can’t hold them accountable if we don’t have a newspaper.

Do you worry for the future? How long do you think you can buck the trend and continue to question the government? What is your biggest challenge?

Yes. I do worry. Every waking hour. The question of how long is immaterial because that is the fundamental job of a newspaper… I think we can do our job as long as we have the support of the readers. The way the wind is blowing, at times I worry our readers may also start doubting our work. They are not isolated; they spend their time watching primetime news. Apart from responsible readership, I also wish our judiciary were more proactive and swifter in upholding media freedom.

Should anyone become a journalist now?

No. (Laughs) I told my daughter not to become a journalist, but she is studying to become one now. This is a demanding profession; first you put in a lot of hard work and then it’s a thankless job with no social life. And, like I told the minister, this is not a job for gentlemen.

My colleagues tell me they dread speaking to me because unlike many others in leadership roles, conversations with me almost always leave them in deeper despair than when they entered my cabin. I do not speak much but if someone asks me something, I try not to mislead them, especially if they are young. I tell them to decide their goals first. If the goal is to be part of a newspaper or be a journalist, no matter what, be one by all means. But then you should also be aware of the consequences. Do not treat journalism like an unhappy marriage. Enjoy the ride. Otherwise, jump ship before it moves too far out in the high seas.

And there’s no money either. Is there any motivation for it at all?

On a serious note, journalism is not just a job. It’s more than that. There is an element of service to it. You may take up a job for money but you may not be happy. In earlier times, people did not join the profession for money, it was not a well-paying job at all. It is in the post-liberalised era that advertisement rates shot up and the salaries of journalists in some, big media houses saw a massive rise. Those days are now over. The current model, unless you sell yourself completely to the government and get support through government advertisements, will not be able to sustain those kinds of salaries.

Your own career started on a humble note with a small Malayalam daily, Venad Pathrika. What kind of influence did it have on you?

I started out at Venad Pathrika in 1989. I was 21 then. Edited by Janardhanan Nair, the paper is now in its 30th year. I was a reporter there but was expected to do everything—it was a small paper, we had to report, edit and sometimes we also had to help with the printing. One of the priceless lessons I learnt then was to write fast—it was an eveninger and the paper had to be printed by 2 pm daily—and also to cope with the condescension of established mastheads. Often, the morning dailies published the same news that the evening papers would have already published 14 hours earlier with so little time in their hand. Yet, the so-called mainstream journalists used to strut around like royalty. The lessons I learnt then helped me treat every newspaper, and now websites, with professional respect. I also learnt to cover the Assembly and crime while I was with Pathrika.

Who or what have been your inspirations?

The legendary CP Kuruvilla (long-term deputy editor with The Business Standard) from Kottayam. He was a complete newsman. A coincidence but not strange: Most of those who taught me journalism are from Kottayam: K C John, Thomas Oommen, Kuruvilla….I learnt the ropes of journalism working under Kuruvilla and Deepayan Chatterjee. It was from them that I learnt how to write headlines. I consider Kuruvilla to be the most courageous journalist I have ever met. I wish he was around now.

I also follow the British and US papers closely; my personal favourite is the New York Times. Few can match its standards.

Why did you choose to live in Calcutta?

In 1991, while I was being trained in Delhi (with The Economic Times), I was told to report for work in Bangalore, a city I did not like. I had never been to Calcutta, and a vacancy popped up in the city just the day before I was supposed to leave for Bangalore. I volunteered and, since then, I have been in love with Calcutta. I had briefly left the city to work in Delhi and Bombay but returned to Calcutta at the first opportunity. I tell my friends in Kerala that one reason (to like the city) is that I can see the sun long before they can every day. I think the real reason is neither my family nor I have ever felt an outsider here. And of course, no one here tells me what I can eat or cannot eat. It’s just like Kerala on that count.

What would be your advice to budding journalists?

Get your facts right. Read, read and read. And write something, anything, even a few lines will do, every day.

![By Stephan Gillmeier [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://kochipost.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Wilde_huendin_am_stillen.jpg)