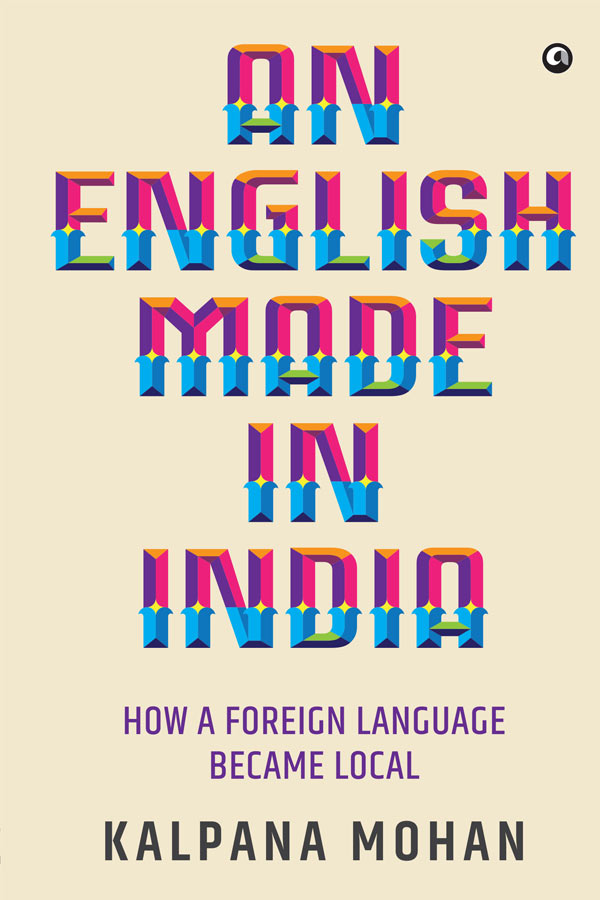

Three thousand kilometres southwest of Dalhousie Hilltop School, at the opposite end of the country, I discovered that in some families in India, the English language had been taught for over 200 years, for political reasons, almost as a matter of necessity. Inside the old royal family of Travancore, Her Highness Princess Pooyam Thirunal Gouri Parvathi Bayi had grown up hearing English spoken around her all the time. Consequently, when she began to learn it formally, it was almost effortless, as natural as paying obeisance to Lord Padmanabha, a representation of the supreme deity Vishnu.

Every member of the royal family of the erstwhile Travancore kingdom was a dasa, a slave, to the god with the rare ‘right-turning’ conch. Even when Princess Gouri Parvathi Bayi travelled to other parts of the world, reminders of home popped up, in the most unexpected places. On a visit to the Isle of Wight, she had just entered the Durbar Room in the Osborne House where Queen Victoria had breathed her last when the princess felt that something in that place was calling out to her. Sure enough, among the displays was a gift to the queen from her family—an ivory carving of Lord Padmanabha.

Likewise, on another visit to the Windsor Castle, she noticed a throne among the exhibits, and told her friend that there was something about it that spoke to her. They walked around to the back of the chair and, there, engraved on it was the emblem of the Travancore royal family, Lord Padmanabha’s conch. When she went back to her palace in the old city of Thiruvananthapuram, the princess discovered that in 1851 the throne had in fact been gifted by her ancestor, the Travancore maharaja, to his pen pal Queen Victoria, for the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in London’s Hyde Park.

The conch seemed to be an extension of the princess herself. It was a feeling both inexplicable and unalterable, beckoning her, at the most unexpected times in her life. Deep inside the ancient Sri Padmanabhaswamy Temple in Thiruvananthapuram, reclining under the hood of the serpent Adisesha lies Lord Padmanabha, Vishnu, whom Hindus worship as the Preserver of the Universe. According to legend, when a hermit blew into his conch during meditation, a snake crept out of it, and directed that he should be worshipped as Naga devata. Built on that sacred ground that was once a forest, the temple has stood sentinel to the fortunes of the Travancore kingdom—one of the oldest dynasties in India whose recorded history dates from 870 bce. Stories about the temple also flourished.

In 1870, a British missionary Reverend Samuel Mateer wrote about a deep well inside the temple ‘into which immense riches are thrown year by year; and in another place, in a hollow covered by a stone, a great golden lamp, which was lit over 120 years ago and still continues burning.’

Even before I landed in this city, I’d heard about the temple’s magnificent seven-storey gopuram (tower) and the fabled Arattu procession that takes place in April and October every year. What is unique about this procession is that it shuts down the city’s international airport for five hours so the deity, the king and the people of the city can walk down the 3-kilometre runway to the waters at Shankumugham Beach. There they immerse themselves, deity and dasa, in a ritual bathing in the Indian Ocean. Meteer’s writings about life in Travancore denounced many of its ancient practices. Yet underscoring his writings was a sense of awe for the enigma of the place that he (and perhaps no one) would ever comprehend.

I’d landed at the Thiruvananthapuram airport early in the evening during a terrible downpour. In the pelting rain, it wasn’t clear where the sky began and the ocean ended. Rain lashed the ground in inch-thick ropes and the umbrellas in Kerala were built to handle them, resembling little black tents with curved industrial strength handles. As my taxi crawled out of the airport, I realized how close the runway was to the waters of the Indian Ocean. Fishermen’s boats lined the sands, reminding me of the events that unfolded in a novella, Chemmeen, that was centred around this southwestern coast. ‘When the first fisherman fought with the waves and currents of the sea, single-handed, on a piece of wood on the other side of the horizon, his wife sat looking westward to the sea and prayed with all her soul for his safety.’ When the woman on the shore was chaste, the goddess of the sea, Katalamma, never failed to deliver her husband back to land, despite the treacherous whirlpools, sharks and storms.

Driving in that devastating rain, I understood why Princess Gouri looked for portents during her travels. Royals and commoners weren’t exempt from tragedy and faith was the only thing that gave people hope. Princess Gouri lost her father in an air crash in Kullu when she was twenty-nine. In 1944, the princess was just three when she lost her six-year-old brother to a rheumatic heart condition. In a strange way, her life crossed mine, too, at the time. My parents were married the year of her brother’s death and my father always told me that the sound of drums was missing at his wedding because the state of Travancore was in mourning. I went to meet the princess at her residence on the grounds of Kowdiar Palace to glean a little more about her education, especially about her English lessons in the early part of the twentieth century.

A conch frieze decorated the front door of her home. The doorbell by the front door was fused onto a base limned as a conch. It adorned light switches. I counted sixteen conches in each window grille at the bungalow. The royal vehicle had the conch emblazoned on the fender. Like all those of her lineage, the princess too believed that the ‘valampuri shankha’ assured fame, longevity and prosperity and as she spoke to me about her feelings in the presence of the sinistral conch, I listened, finding it hard to maintain my scepticism.

The princess spoke perfect English, as did her mother and her grandmother before her, and as did most educated Indians who had grown up in homes where English was also a familiar tongue. But Parvathi Bayi spoke with a certain flourish and colour, too, and with a wryness that came from an eye for irony, and with the sort of precision that I’d only heard from those who were educated in the early to mid-twentieth century, many of whom had been taught by Englishmen or by Anglo-Indians or by Indians who wielded the language as well as their imperial masters.

There’s a caveat, however. The second the princess uttered some words which ended in specific sounds—‘hall’, or ‘soon’, or ‘people’—the pixie dust sloughed off her cotton kasavu sari. In a blink of an eye, the princess morphed into a commoner like me whose father could not afford to give his child a convent school education. All I heard was her strident affirmations and her weighty and hardened ‘l’ and ‘n’, which she enunciated, like most Malayalis—and all my maternal cousins who, like me, had also been born in Travancore—with the curl of her tongue against the posterior roof of her mouth.

Sitting in the bungalow adjacent to Kowdiar Palace, I discovered that, at seventy-five, Princess Parvathi couldn’t be bothered about the trivialities of accent and style. Unlike the kingdoms in the north of India, the Travancore royalty had never valued opulence or artifice, eating out of banana leaves while seated on the floor just like the common folk did. In any case, she said, how on earth did it matter that she spoke with an Indian accent or that the English that Indians spoke often showed the petticoats of its origins? ‘Don’t the French have an accent when they speak English?’ she asked. ‘And the Germans?’ The princess was right. She had put my common mind in its place and admonished me, in a sense, just as my husband often did.

* * *

When she was about five years old, right around the time India gained independence, Princess Gouri played hostess to eighteen-year-old Pamela Mountbatten, the daughter of Lord Louis Mountbatten, the last viceroy of British India and the first governor general of independent India. Lord Mountbatten and his family were headed for the Periyar Game Sanctuary (now part of the Periyar Wildlife Sanctuary) in the Western Ghats and they had stopped to greet the Travancore royals 3,000 feet up in the hills at Peermade. As per etiquette, Lord Mountbatten sat at her uncle’s table and Lady Edwina at her mother’s table while the little princess had been assigned to take charge of Pamela. She had been coached to ask Pamela what she wanted to drink. ‘Would you like coffee or tea?’ she asked. Since Pamela responded with ‘tea’—and that being a foregone conclusion—the princess had been primed to ask the subsequent question. ‘Would you like milk or lemon with that?’ At the end of the tea and the mingling, Lord Mountbatten was so taken with how well-spoken the five-year-old princess was that she was whisked away for a photograph with him, a picture that the princess could not locate as I sat with her at her guest house at Kowdiar Palace.

But in her descriptions was a revelation of how children of the Travancore royal family were groomed early for formal, diplomatic functions. As was customary in the state of her birth, the princess began learning to write the Malayalam script by scrawling with her finger on sand so that she never lost touch with the earth. The priest held her finger and made her write out the words ‘Hari Sree Ganapathaye Namaha Avignamasthu…’ invoking Lord Ganesha to remove all obstacles in her progress to education and the Goddess of Learning, Saraswati, to pave the way.

One year after she began learning Malayalam, at about four years of age, the princess was initiated into the English alphabet, although she was already speaking the language fluently by then. Early on, the princess was perplexed by the unpredictability of English. ‘Cut. Put. But. They’re written the same way but pronounced differently,’ she would say to her English tutor, Mrs Myrtle Pereira, who turned up at the palace for her lessons every day. ‘That’s the way it is, child,’ Mrs Pereira said, suggesting that the best way to master the language was to accept its inconsistencies, memorize them and move on. The princess had asked a thoughtful question to which the response was labyrinthine.

Excerpted with Permission from the book An English Made in India, How A Foreign Language became Local; Published by Aleph Book Company

Cover Image: Kowdiar Palace, Thiruvananthapuram; Credit: Wikimedia Commons