Bearing in mind Dr Ambedkar and Mahatma Gandhi’s views, I would like to elaborate on how to eradicate caste system in contemporary India. Before I delve deeper into this topic, a matter of great importance is to analyse the kind of approach that should be taken towards caste eradication. We have a vast collection of anti-caste writings in Malayalam as well as in other languages. Historically, one finds that great efforts were made to eradicate caste system since colonial times at various levels and places. Though such efforts and experiences were collected and recorded, the hard-hitting reality is that caste still plays a significant role in our society.

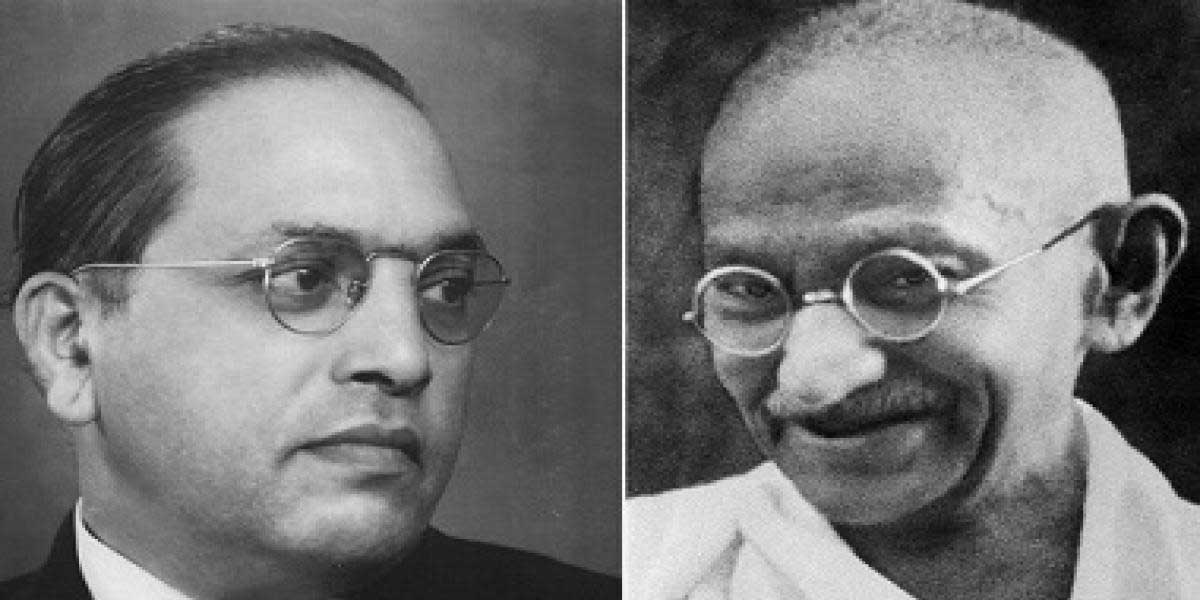

We have to be cautious in our approach towards this subject as we have to set aside preconceived notions that a particular stream of thought in history is the accurate one and the rest are all erroneous. Hence my approach towards this subject will be primarily to inspect the viewpoints of B R Ambedkar, Mahatma Gandhi and Ram Manohar Lohia regarding the social reality of the caste system and the logical conclusions they reached in this matter. Only from such an examination can we have a right approach towards caste annihilation.

Caste system was an important matter which influenced our thoughts both politically and socially in India from early 19th century itself. There was an important school of thought which recognized caste system as a social reality. Their view was that caste is not merely an attitude of people but is a physical and social reality outside the human mind. A person cannot decide whether to be inside or outside the caste system.

In such a school of thought which has many streams, there is one that argues that caste system determines the fundamental nature of the Indian society. According to them, as far as the Indian society is concerned, caste is considered as an all permeating system which determines our socio-economic, political and moral life. One of the most important arguments of this school of thought is that it’s only through progressive changes in the caste system can India achieve considerable social progress. Reformers like Jyothrao Phule said that caste system needs a major overhaul in order to bring about social reform in Indian society.

Another school of thought, largely of scholars, was gradually emerging in the 19th century who believed that the caste system was not that significant during the phase when India was in the process of transforming into a modern nation. According to them nationalism, citizenship and political sovereignty is of more significance and hence radical reforms in politics should take precedence over social reforms. We have to primarily understand that even in contemporary India, argumentative positions of both these schools of thought are creating a great impact on our socio- political beliefs. If we do not segregate these arguments in our analysis, we might misinterpret caste annihilation as an agenda only driven by a particular group belonging to the so-called lower strata of our society.

As a foreword, I would like to say that we should recognize the fact that Mahatma Gandhi and B R Ambedkar represent two very significant schools of thought in relation to caste system in history of India. The leader of Indian Socialist movement Ram Manohar Lohia too formulated another unique view on the caste system and put forward a plan of action for a social movement before us based on scientific awareness.

I would like to mainly emphasise in this talk on the historicity of the logical conclusion reached by Mahatma Gandhi and B R Ambedkar on caste and caste annihilation.

Mahatma Gandhi has played the most prominent role in the social and political history of modern India. Mahatma Gandhi is perceived critically by many today. A strong subtext of Dalit criticism of Gandhi also exists. The pivot of such criticisms lies in the critique that Gandhi was against the political rights of many sections including the Dalits. This is in the context of events of 1932… I do not accept such a criticism. I feel while viewing things in the context of annihilation of caste, we should examine Gandhi’s arguments in a broader perspective.

There are many myths prevailing in our society with regard to Gandhi. The belief that Gandhi has written his well-known book Hind Swaraj with the intent of taking an alternative position within the Indian society is wrong. Most debaters forget that the roots of the Hind Swaraj lie elsewhere. Anyone who reads Hind Swaraj can comprehend that the ideas of Hind Swaraj sprang from the premise of alternate positions in European society while Gandhi was living in Europe.

In Hindu Swaraj, among the books recommended by him to be read by all of us, there is only one book by an Indian author. The rest were all written by European authors. I am citing this example to say that all ideas of Gandhi including Hind Swaraj were “Indian” is actually a myth. He has openly admitted in Hind Swaraj that Tolstoy was his spiritual guru. He never accepted any Indian as his spiritual guru. In fact Hind Swaraj idolises alienated European values, which while staying within a violent European environment, fought against atrocities, stood for vegetarianism and non-violence and, celebrated simple living.

Gandhi’s grandfather was the prime minister to the King in Kathiawar. As per one of his biographers, Gandhi who came from a family closely associated with rulers, never lived in any of the Indian villages. There is no objective evidence that Gandhi had any experience of life in rural India particularly, before the book Hind Swaraj was written. I would like to indicate that in our approach towards Gandhi we should realise that the belief that Gandhi’s root was primarily Indian and that he was advocating Indian ideology and he established an Indianised concept quite early in his life is historically untrue. We can have better clarity on Gandhian concepts only if adopt a historically true approach.

We can find a long list of Gandhian scholars both in India and around the world. Few among them have pinpointed the many contradictions in Gandhi’s stance (perspective) right from the beginning till the end. Gandhi has always maintained that there were no contradictions in his stance. Gandhi has further said that if he has come out with different opinions on a particular subject, it’s the final view point which has to be taken into consideration as his and not the previous ones.

I don’t see any fault in this. On the other hand what I am trying to say is that Gandhi’s viewpoints kept changing. The static notion that Gandhi was a complete philosopher who had intuitional knowledge is actually incorrect. We can better understand this when we go through Gandhian literature.

We should have a dual approach towards Gandhi’s viewpoints on caste system which he had expressed in the early stages. As an individual, Gandhi did try to cut across the barriers of caste system. In his book, My Experiments with Truth, he says that at an early age of twelve itself he had embarked upon this. If we can believe him, one of the stories recounted in his book is that he refused to purify himself after being asked to do so by his parents for touching a untouchable manual scavenger who had come home to clean the toilet. We can see that throughout his life on many occasions he has tried to cut across caste barriers but on certain other occasions he has acted in a casteist manner too.

It’s a matter of significance that when it was a taboo for Hindus to cross the seas, Gandhi left the country for Europe by ship. He embarked on his journey braving challenges including excommunication from his own community. Thus as an individual he cut across the barriers created by caste. At the same time when his eldest son wanted to marry outside the community Gandhi discouraged it and the marriage was cancelled. Later Gandhi, who belongs to the Vaishya community, gets his younger son married to a Brahmin girl. He was also witness to a Brahmin boy’s marriage to a Dalit girl who was residing in his ashram. I am citing all these events to indicate that when we analyse this particular aspect, we should avoid the approach that Gandhi remained consistent in his perspectives on the caste system from the beginning till the end.

It’s quite significant that Gandhi has made some correspondence on caste system with Ambedkar in which he has made a few statements. He said that, “Caste and religion are not inter-related. Caste is a ritual and its origin is not known to me. I don’t need to know that to quench my spiritual thirst. This was one statement he made on the caste system. We should analyse the term “spiritual thirst” in detail. Someone asked Gandhi, “You fought for our freedom facing so many difficulties? You were at the forefront of our freedom struggle? What is your view on that statement?

Gandhi’s reply was that one should never say that he got us freedom with great difficulty. His life would have been the same even if India never got freedom. Gandhi openly declares in his book, My Experiments with truth, that his only duty was towards the spiritual call coming from inside his soul and he need to do justice only to that…

This explains why he said that caste and religion is not inter-related and also that he doesn’t need to know the source from which the caste system originated. He says that these are irrelevant as far as his spiritual thirst is concerned. Gandhi interpreted caste system not as a historically evolved social institution but as an aftermath of human moral disintegration.

Based on his interpretation that caste system was the outcome of human moral disintegration, Gandhi emphatically says that opposing caste oppression is human moral responsibility. Naturally, the logical conclusion that Gandhi reaches through this interpretation is that caste discrimination is not the issue of rights of one who is discriminated but that of the moral privilege of the ones who discriminate.

Gandhi comprehended caste system as a problem which has to be morally resolved by the upper caste. This understanding hinders Gandhi from forming an opinion on how to tackle caste discrimination and eradicate it. As a matter of fact, Gandhi reaches the logical conclusion that ideally if caste discrimination is eradicated, the division of classes based on caste will be an exemplary model for the whole world.

Gandhi accepted only varna (class) not caste. As far as India is concerned, both caste and class worked in the same way. Gandhi’s view that such a socially divisive order is a model for the whole world disallows him to understand caste system historically. This view also leads him to reach the logical conclusion in a narrower sense that caste system is just a moral issue.

If we study Gandhian literature we will be unable to find the word caste annihilation. Gandhi’s approach towards caste system would not have naturally led to the word caste annihilation. Instead, beyond thinking that the discrimination in an inter-caste relationships needs to be ended and the need to democratise the same, one cannot find any observation in Gandhian literature that caste system is a destructive social institution.

Another important matter that he states is that a Hindu cannot exist without believing in caste and varna. A person who does not accept varna cannot be a Hindu. He questions how a Muslim who rejects Quran can consider himself a Muslim and how can a Christian who rejects The Bible consider himself a Christian? He also wondered if terms like caste and varna are interchangeable and if varna is an integral part that defines Hindu-ness. If so, then how can a person who rejects caste and varna call himself a Hindu? These statements reveal that the caste and varna system which exists as the basis of the Hindu society was never renounced by Gandhi. For the very same reason, Gandhi’s conceptual universe never thought about caste annihilation.

Speaking on the benefits of the caste system, he goes on to say that it is essential to continue with the tradition of family occupation. He justifies this by saying that by continuing with the family occupation, upholding the tradition of son taking up his father’s occupation and continuing with the tradition through generations will enhance their labour skills.

In an article which Gandhi wrote in 1936, he says that in India, scavengers who clean toilets and carry faecal matter is a large community which has great knowledge about faeces. By saying that scavengers have great scientific and meticulous knowledge of faecal matter, Gandhi had exalted the occupation of scavenging. In fact, this exaltation of scavenging is a problematic outcome of not perceiving caste as an oppressive institution which came into being historically. The inability to perceive caste system in such a manner is not a problem related to his spiritual hunger.

For the very same reason, Gandhi was never as much concerned much about the freedom struggle as he was about his spiritual awakening. There is no doubt that Gandhi’s universe was that of a man who was compassionate and humanitarian. In order to test the tenacity of his celibacy (Brahmacharya), Gandhi lay naked along with his young female companions. While, Gandhi has every right to test his virtue of celibacy, he never gave a thought to the state of mind of the girls. And consent would mean nothing when Gandhi’s stature and his position in the society were taken into account. He perceived the world as a testing ground of his life.

India’s freedom struggle led by Indian National Congress was also a testing ground for Gandhi. When he was getting ready for such experiments he doesn’t give in to those who tried to stop him. We should keep in mind that Gandhi had his own schemes to make imperative changes in a society dominated by caste system.

I have no doubt regarding Gandhi’s sincerity to eradicate caste discrimination and also in his attempts to end the atrocities against the untouchables. History does not demand just sincerity. History demands in-depth vision along with sincerity. History requires a comprehensive perception. In the absence of such a historical in-depth perception, caste annihilation or a casteless society was not a need as far as Gandhi was concerned.

In India, the words “caste annihilation” and “casteless society” were first coined by Dr Ambedkar and his school of thought. As I had earlier mentioned, there was another school of thought which formed during the period of Indian freedom struggle. The most significant hypothesis that is commonly shared unanimously amongst us is that the Indian nation came into being as a result of the anti-British struggles. But we should understand the fact that it’s not just these anti-British struggles, but also the struggles for rights and for a more democratic society by various sections of the society which resulted in the birth of democratic India. It’s when we fail to understand the political vision and wisdom gained from these struggles for internal democracy that all the great Indian social reformers get erased from the memory of history. They get reduced to a group of people who stood up for only a certain section of the society and thereby we arrive at the wrong assumption that the Indian nation was the imagination of only the so-called nationalists.

Dr Ambedkar stood firm in this stream of widespread protests which stood for internal democracy. He published a seminar paper while exploring the Indian castes in 1916. He explains the fundamental concept of caste system in India, its genesis, nature and conventions in his paper.

According to the concepts of the scholars until then, one of the fundamental virtues of caste system was occupation. Occupation is based on the caste one belongs to. This is one concept. The concept of purity was another one. These two were the most significant concepts which led to the notion of purity and impurity which makes an individual good or bad in the eyes of society. This is the fundamental basis of caste segregation and discrimination of the society. Annie Besant who is the jeevathma and paramathma of the Theosophical society argues in her lengthy article that people who came from the lower caste communities take food which has stench and hence they have a repulsive odour which naturally became the reason for keeping them away. We have to see that even Annie Besant nurtured such strange thoughts.

Dr Ambedkar puts forward his arguments opposing both these concepts. It was he who first explained that caste division was not segregation of occupations but the segregation of workers. It was Ambedkar who also said that the Indian caste system is not about division of the workers based on occupation but all about hierarchical segregation of people. If we say that caste system is segregation based on one’s occupation then when occupation changes caste also should change. Contemporary India recognises the fact that no matter which occupation you engage in, even if one changes it, whether one likes it or not, caste is not going to leave him or her. This is the reality before us. Therefore our social experiences itself rejects the theory that occupation is the prime reason why casteism came into being.

Ambedkar specifies that the workers are segregated and arranged in various orders but not based on their occupation. By refusing to share food with an untouchable at the dining table, we are committing a social crime. It’s not due to an issue with the sense of taste but an internal moral consciousness that stops one from sharing the food with him. Hence it is a social crime and not an individual crime. When a child is born he is imparted with this lesson at his home and school, by his fellow-classmates, friends, brother, sister, mother, church and the priests which makes him withdraw his hand from the food served. This revulsion is a social conditioning. It has no connection with hygiene.

Ambedkar went abroad and got himself highly educated but on his return he is humiliated by a Brahmin who had not even cleared his fifth grade exam. He refuses to give even a glass of water to Ambedkar. Casteism is not the outcome of being hygienic or unhygienic. It is not the outcome of being educated or uneducated. Ambedkar disagrees with both these important theories. According to him there was another significant reason why casteism came into being. By virtue of Anthropology, he proclaimed that casteism was the outcome of enforcing the system of marrying within one’s own tribe, endogamy, over a system of marrying outside your tribe, exogamy…

It’s Dr Ambedkar who first said that caste system is the first social institution in history which has its roots not in relations of production but in relations of reproduction. Ambedkar found that practice of Sati was the outcome of precautionary measures taken by the society when it transits into a custom of practicing endogamous marriages. We know that sati was the customary practice of immolating the wife on her husband’s funeral pyre. According to a Sanatan Hindu it’s the act of wife immolating herself by jumping into the funeral pyre of her husband. In case she refuses to do so, she will be forcefully thrown into the pyre. This was the job of the Hindu. On being questioned on how such a strange custom became prevalent in India, Ambedkar’s logical response was that one should hold the caste system responsible for this. If a caste has to survive the ratio between men and women should be equal. When a man dies, a woman becomes surplus. This surplus woman is a threat to the survival of that particular caste because there is a possibility of her either marrying from outside her caste or else she might lure an eligible man of marriageable age from the same caste into marriage. She is a threat at any cost. There are only two ways by which this threat can be curbed. One way is to burn her to death on her husband’s funeral pyre. The other way is to coerce her into widowhood.

Ambedkar finds that the real roots of these practices lie in the caste system which is well aligned through endogamous marriages. While defining the nature of caste system he says that we should look not just into the economic relations but also into the reproductive relations. He defines caste system as a social institution which influences all kind of transactions within the society.

Manu in Manusmriti is not the inventor of casteism. Ambedkar observed that Manu just compiled the rules of casteism. Therefore Ambedkar never had the misunderstanding that the sole culprits behind creating casteism was the Brahmin community. Ambedkar also points out that despite the existence of inequalities in all the societies around the world, it’s only within the Indian society that we can find such extensive literature which justifies inequality. Only caste system has a narrative network and a theoretical foundation provided by thousands of books and legends which maintains the purity of caste almost completely. There is no socially divisive system anywhere in the world other than the caste system of our society which enjoys such a theoretical backing.

Ambedkar finds that the foundation of Indian morality lies in the religious philosophy and awareness that justifies these atrocities. He also accurately explains that the moral awareness of an Indian is structurally graded with respect to the caste system.

I would like to touch upon few arguments that Ambedkar puts forward in his theory of caste annihilation. In his book Annihilation of Caste, there are around twenty analyses regarding the survival of caste system and its methods of operation. We must understand that the process of social reforms was understood in two ways in India. One among them is that the concept of social experiment in the 19th century was actually reforming the family system. One of the schools of thought believed that social reforms would remove the taboos in the caste system. For example, overcoming the rule that women should not be educated by sending them to school or, challenging the rule that one should not cross the seas. The act of violating caste-related taboos within the caste system was perceived as social reform by one of the prominent schools of thought among Indian social reformers.

Another school of thought was that social reform movement is about reforming the society as a whole. W C Banerjee, who was the president of Indian National Congress, believed that political reform was imminent in India. An excerpt from one of his speeches as quoted by Ambedkar is as follows: “I cannot tolerate those who believe that we are not in a position to have political reforms unless our social condition is reformed. I do not see any correlation between the two.” The predominant theory was that social reform should be within the caste itself. W C Banerjee said that even if we do not do any of this, we are still in a position to have political reforms.

In response to this, Ambedkar hypothetically throws a few questions at him. Some of the questions was as follows: When you do not allow crores of Indians to use the public road how do you qualify for political authority? When you do not allow entry of millions of Indian into schools, how do you qualify for political authority? Therefore social reform is not just the violation of caste-related taboos within the caste system but in empowering the people by creating basic rights for those who are deprived of it. This was the school of thought that believed that social reform is in ensuring the right to use of public spaces to those who were deprived of it.

Throughout history we can observe that there were consistent clashes between these schools of thought, one of which argued that social reform is in violating the caste-related taboos within the caste itself whereas the other believed that social reform is in rewriting the fundamental social structure of the Indian society. B R Ambedkar represented the school of thought which believed in a complete overhaul of the Indian society.

Later, when castes are supposed to be in retreat, becoming irrelevant and disappearing, when classes are becoming more relevant, he says to the socialists that problems of casteism cannot be solved by establishing economic justice. Ambedkar says this in 1936. The essence of the problems created by casteism is not because of economic inequality but lack of dignity. As long as one’s moral consciousness refuses to accept the other person as dignified as you are, he cannot do anything about it. Ambedkar’s critique against the socialists was that by believing that economic justice was the only solution, they failed to understand the reality of caste system. He also warns them that even if they succeed in the revolution against caste system, the very next day itself they would have to address the issues of casteism all over again. An important fact to be noted is that casteism is not an issue related to poverty. Those who belong to a backward caste may be poor but the crux of the matter is not poverty.

I do not understand what poverty has to do with mocking someone like K R Narayanan based on his caste. I know of a joke that people laughed at when he visited Kottayam. Kerala is a place where there are social miscreants who laughed at K R Narayan saying that while he was about to hoist the flag at Red Fort on the 15th of August, it’s quite likely that he mistakes the flag post to be a coconut tree and might start climbing it. In other words, according to them, K.R Narayan’s hereditary occupation was climbing the coconut tree and that can never change. Even if it was a global citizen like K R Narayan, who left Kerala in his early years for Delhi, went to Oxford for his higher studies and after returning became a Union Minister, got married to Usha who was a foreigner.

This is the falsehood that caste system teaches us. There is a proverb in Malayalam, “paravande makan pattalathil poyath pole” which can be translated as “like how a paravan’s son goes to join the army” which means that no matter where paravan’s son goes or even if he becomes the president, it’s of no use. This has to be seen as our immoral philosophy. We have already decided that what’s bred in the bone will come out in the flesh. The issue with casteism is that we are highly influenced by a morality which is both anti-social and inhumane.

This is not an issue related to poverty. If it was a poverty related issue it should affect only the poor. It’s not only affecting the poor but also the rich. Jagjivan Ram was the deputy prime minister of India. He once unveiled a statue at Varanasi. As soon as he left, a Brahmin who hadn’t even cleared his second-grade exam conducted a purification ceremony at the venue.

Thus, after elaborating on the working of the caste system on various levels, Ambedkar reached the conclusion that inter-caste marriages is one of the solutions to eradicate caste system. According to him, only a society which takes form after the mixing of blood can successfully come out of casteist thoughts. While he agrees with inter-caste marriages, he also raises the question why such a practice is not so prevalent. Ambedkar’s answer to that question was that Hindu religion grants its believers a religious consciousness which does not allow the practice of inter-caste marriages. Man continues to carry the awareness that one should not marry from another caste as it’s prohibited by his religion. Ambedkar does not define Hindu religion as a prophetic religion. He does not believe that Hindu religion has any factor which liberates man. He says that Hindu religion is a religion of prohibitions. It’s a religion of rules. These rules are detrimental to social mobility and progress. He also concludes that we can remove the belief in caste system only by completely discarding Hindu philosophies and mythologies.

While reaching the above conclusion, he also answers the question as to why we are unable to annihilate caste system using such a method. His response to the question was that the Brahmin community whom the Indian society views as intellectuals has no interest in it and are also actively working against it. He points out that the same community is in the forefront when it comes to fighting for economic and political justice. Ambedkar also raises the subversive question as to why the Brahmin community does not take initiative in the fight for caste annihilation. This is a very significant matter.

Someone who is travelling by train cannot stick to the rule of untouchability. This was part of a great revolution that happened in India. Buses and trains are social reformers. Once you enter them you cannot help getting squashed in the crowd. You want to ask untouchables to move twenty four feet away but the bus itself is only twenty four feet long. Hence it’s impossible.

So far I have been talking about the horizontal structure of the caste system. One of the most significant limitations of caste-related discourses is the horizontal structure of caste system. Caste system has a horizontal constitution. Despite being arranged in vertical order, every caste is structurally horizontal. In the case of the castes of Kerala like Ezhava and Nair, it works on a horizontal structure. The significance of this horizontal structure is that it provides a protective cover to every individual.

We should know that the utility value of caste has increased tremendously in the contemporary times. In debates on reservation, people argue that it’s reservation that helps caste system survive. I have a counter question to ask. Why do people who do not enjoy reservations carry their caste with them? In this area of horizontal structuring, individuals enjoy a huge protective cover. Prima facie he depends on his caste. The most significant reasons why caste system still survives in our society is because of this horizontal composition. This applies both to the lower and upper strata of the society.

The truth is that it has been more empowered by institutionalising it. When it’s said that Keralites are immigrants, I would study society only on the basis of caste-wise data. The Syrian Christian community from the district of Kottayam in Kerala is the one which migrated mostly to other countries. They are from the same district where I hail from. The reason for their migration was mainly because they were well-informed about those countries like Australia and England. The modus operandi of a Syrian Christian is community-wise, when he lands in Mumbai, Delhi or Bahrain. This is applicable to all communities. The issue that I face when I travel to Europe is that since there are no people belonging to the scheduled caste, I cannot depend on anyone there. To this end, we should be aware that we are discussing the topic of caste annihilation when the utility value of caste is rising. We cannot perceive this as a matter which can be sorted out just by the organized strength of those from the lower strata of the society. You are fighting against superstitions. I believe that this should be your prime responsibility.

Ambedkar believed that the purpose of caste annihilation is to create a modern human, bypassing all the superstitions that have been prevailing in India. This is not something which we can achieve in a short span of time. We have to accept the reality that caste annihilation does not mean that caste will not exist. This is actually because of the utility value of caste which is horizontal in structure. If we have to reduce this utility value we have to draw society towards democracy which respects and gives dignity to individuals through the ideas of liberty, equality and fraternity. Arundhati Roy recently wrote an introduction to Annihilation of Caste. I have some difference of opinion with her but I would like to share with you the conclusion reached by many including her.

She wrote: “Can caste be annihilated? Not unless we show the courage to rearrange the stars in our firmament…not unless those who call themselves revolutionaries develop a radical critique of Brahminism, not unless those who understand Brahmanism sharpen their critique of capitalism and not unless we read Baba Saheb Ambedkar.”

Reading Ambedkar is a revolutionary act as far as India is concerned. I do not believe that Ambedkar is the last word on everything, but I believe that he is certainly a new window to the study of our society. While thinking about caste annihilation, we are obliged to take into consideration the views of all the three: Ambedkar, Gandhi and Lohia. But it is the ideas of Ambedkar that throws light in our activities towards achieving the task of annihilating caste

This speech was delivered at a Freethinker’s meet in Thiruvananthapuram on April 23, 2017. Translated from Malayalam by Deepa Raj