It was a gut-wrenching sight when Malayalam Television stations flashed poignant scenes of the landslide at Kottakkunnu in northern Malappuram district, where the body of a two-year-old boy was recovered clinging to his dead mother. When the landslide struck and mud and debris entombed their home last Friday, 22-year-old Geethu had tried to shield her toddler by tightly embracing him. Rescue workers struggled to separate the entwined bodies.

The accident occurred while Geethu’s husband Sharad was diverting the small stream that was gushing into his backyard. Sharad had a providential escape but his wife and child were not so lucky and his mother Sarojini is still missing.

The rescue operations face severe hurdles in Wayanad and Malappuram as rain continues to bombard areas susceptible to landslides. Central forces and the National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) on rescue operations in landslide-hit areas are finding it challenging to unearth people buried under the debris and tons of mud. While landslides, mud slips and flash floods continue to cause enormous amount of misery in the hill areas, reports from coastal regions give the picture of a turbulent sea gnawing away at the human settlements. The general impression of Kerala as a totally safe zone is turning into a fable now.

Though the intensity of rains have reduced in the last two days, climate-change induced floods has thrown life out of gear in the hills and mid ranges. According to available statistics, the death toll is now at an alarming 97 and likely to mount, and 2, 50,638 people have been rendered homeless. And 58 people continue to remain missing in landslide-hit areas of Kavalappara in Malappuram district and Puthumala in Wayanad. In these areas, adverse weather conditions continue to hamper rescue and rehabilitation works.

Exactly a year after what was said to be the worst flood in a century, the same pattern is emerging, terrifyingly the new norm—the South West Monsoon was tepid in June followed by scanty rainfalls till July end, with intense rainfall in August. The poor Monsoon in June and July had affected both drinking water distribution and agricultural activities and Kerala assumed it was heading for a drought after the deluge in 2018. However, August threw up a completely different picture, mirroring the weather pattern of 2018, with continuous rains and flash floods bursting banks of major rivers wreaking havoc.

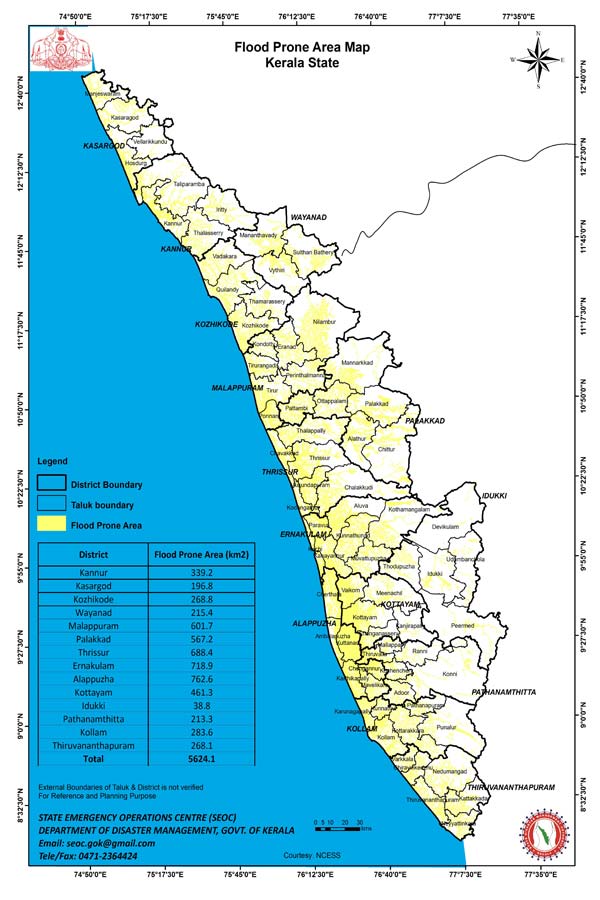

Kerala now finds itself in the Zone 3 of the Hazard map prepared by the Union government. According to experts, 9 percent of the entire state is highly prone to landslides. Rampant reclamation of paddy fields and wetlands accompanied by large scale operation of granite quarries in environmentally fragile areas are contributing factors, further aggravated by climate change. Though the state government ordered closure of some 850 quarries and mines in the state temporarily and warned against illegal construction in environmentally fragile lands, experts say the larger issue of climate change should be addressed by the state on a war footing.

Kerala now finds itself in the Zone 3 of the Hazard map prepared by the Union government. According to experts, 9 percent of the entire state is highly prone to landslides. Rampant reclamation of paddy fields and wetlands accompanied by large scale operation of granite quarries in environmentally fragile areas are contributing factors, further aggravated by climate change. Though the state government ordered closure of some 850 quarries and mines in the state temporarily and warned against illegal construction in environmentally fragile lands, experts say the larger issue of climate change should be addressed by the state on a war footing.

The repeat of last year’s fury on its first anniversary reiterates that climate change is no an old wives’ tale but is clearly upon us. For Kerala, it is time to think urgently of measures for future preparedness and mitigation. Future monsoons would be more devastating in all likelihood. Climate experts say the mood, character and form of rains have changed drastically in the last two years. Eight districts in the state had witnessed eighty landslides between Friday and Sunday alone.

The prevailing situation points to the lack of a scientific flood and disaster management system. The steps taken since the last flood to avert further calamities seem to have evoked no positive outcome. While 1206 relief camps are accommodating over 2, 12,000 people across the state, the rest of the flood victims are struggling hard to rebuild their lives by staying in rented accommodations and houses of relatives.

After the deluge last year, Kerala government and its research agencies had predicted that there would not be a repeat of the disaster in another 100 years. They termed it a once-in-a-century phenomenon. Nobody raised the issue of climate change in the debates that followed the 2018 deluge.

In the previous year, there were allegations of the meteorological department not alerting the state government in advance about the quantum of rainfall that fell during the period. It has been claimed that the government had delayed opening the shutters of dams in the state as a result. This time around, though most of the dams are half empty, flash floods caused landslips in areas far from dams and rivers.

Climate experts have now predicted that floods would recur at five-year intervals instead of the historical once in a 100 year phenomenon. Having faced two successive floods in two years, Kerala should be prepared to face more catastrophic deluges in the coming years.

Are we ready?