In recent years, there has been an alarming spike in mob lynching incidents across the country. Most of the violence is directed against minority communities, creating a sense of insecurity and fear among them. In the backdrop of violence, hatred and bigotry, do we need to revisit our laws? Is there a need for a cohesive, clearly-defined law against lynching?

Cow vigilante violence involving mob attacks in the name of protecting cows targeting has risen since 2014. Most states in India have banned cattle slaughter. Taking the law into their own hands, these cow vigilante groups, claiming to protect cattle, have been responsible for several lynching deaths. Acts like former Union Minister of State Jayant Sinha’s garlanding of the Ramgarh lynching case accused seems to have emboldened and encouraged them.

According to a Human Rights Watch report, more than 100 cow vigilante attacks occurred in India in the last three years; “44 Indians, 36 of them Muslims, were killed and 280 injured” in these attacks, adds the report.

There is no codified law against lynching in India as such presently. The Supreme Court in July 2018 directed Parliament to draw up anti-lynching laws but the Modi government has passed the buck to state governments shrugging off all responsibility citing it was a state subject.

Manipur was the first state to come up with some bold initiatives. It passed a law against lynching that covers many forms of hate crimes: “any act or series of acts of violence or aiding, abetting such act/acts thereof, whether spontaneous or planned, by a mob on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth, language, dietary practices, sexual orientation, political affiliation, ethnicity or any other related grounds”. This law also penalizes dereliction of duty by public officials who fail to protect vulnerable sections.

Madhya Pradesh is the next state in India to introduce a law against lynching. The state Cabinet has proposed an amendment to the existing law against cow slaughter to deal with the recent spike in lynching incidents. The amendment will equip the existing law (Agricultural Cattle Preservation Act) with provisions to combat and contain mob violence. This includes a jail term of a year to five years along with a fine.

On 5 August, 2019, the Rajasthan Legislative Assembly passed a bill providing for life imprisonment and a fine of up to Rupees 5 lakh to convicts involved in mob lynching leading to the victim’s death. Strangely, the legislation has come under attack from the opposition Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) in the state as “minority appeasement”, perhaps betraying the patronage extended by the affiliates of the Hindu nationalist party towards these cow protection groups.

On 12 July, 2019, the Uttar Pradesh State Law Commission submitted a draft bill recommending up to life imprisonment for mob lynching crimes. The Commission stressed that the current laws are not adequate to curb cases of lynching and that there needs to be more stringent action.

But the question arises, “Will laws against lynching help? Or do we just need stricter implementation of existing laws? Is hate and bigotry being normalised?”

There are diverse views among the lawyers’ community on whether there should be a separate law on lynching. Gaurav Pathak, an advocate practicing in the Supreme Court said, “Lynching is a murder any which way and requires the highest form of punishment. What difference will a new law make? Do we need a new law?” He added that there was an urgent need for sensitization and more policing. People should be made aware of the law. Death penalty is the highest punishment and should be enough of a deterrent.

Anas Tanwir, a Supreme Court advocate, was part of the team that drafted the anti-lynching law—MASUKA (Manav Suraksha Kanoon). Tanwir said that the law was drafted almost two years ago. “There is definitely a need for a new anti-lynching law. Manipur, UP and Rajasthan used our template when they drafted their anti-lynching bills.”

He added that in the anti-lynching case in the Supreme Court, the court, in its judgment, issued certain guidelines for the impending law on mob lynching. The guidelines were divided into three categories: preventive, investigative and rehabilitation of the victim. Tanwir said that he feared the Centre may not come up with an anti-lynching law.

Archana Pathak Dave, advocate, Supreme Court, also stressed that a separate law on lynching was required seeing the upsurge in the incidents of mob lynching. It had become a separate crime altogether and had not been defined in the Indian Penal Code (IPC). She added that law and order was a state subject and each state where such incidents occurred had to tackle them.

There has been an alarming rise in the number of incidents of cow vigilantism since the BJP came to power in 2014. The frequency and severity of cow vigilante violence has been unprecedented. Human Rights Watch attributed the surge to the recent rise in Hindu nationalism in India. Leading attacks throughout the country, extremist Hindu groups have targeted Muslim and Dalit communities. Dalit groups are also vulnerable to such attacks as they carry out the work of disposing cattle carcasses and skins.

Cow protection vigilante groups have mushroomed in hundreds, perhaps thousands of towns and villages in northern India. There were an estimated 200 such groups in Delhi-National Capital Region (NCR) alone. Some of the larger groups had up to 5,000 members. The gangs consist of volunteers, mostly young people, many of whom are jobless. Often the youth are motivated emotionally by showing graphic videos of animals getting tortured. The vigilantes often have a widespread network of informers who alert them to supposed incidents of cow slaughter. They also rely on social media of late.

Considering that mob lynching is a pan-Indian occurrence, it is high time that State governments took measures to curb this horrendous crime. There is an urgent need for a separate, effective law to check this growing menace. If states frame stringent laws against mob lynching, the menace of cow vigilantism will also be checked to some extent.

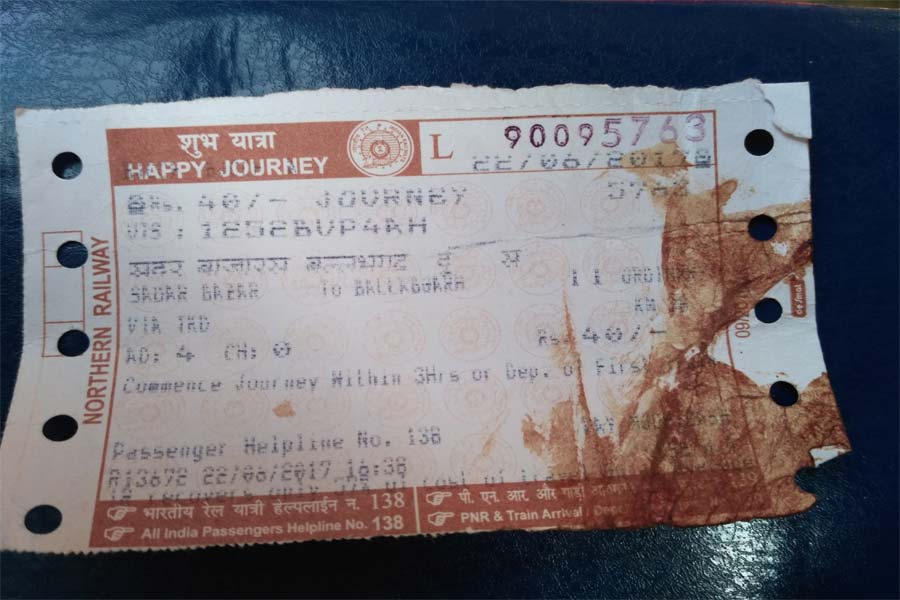

Cover picture: Junaid’s blood-stained train ticket on his fateful journey; Pic credit: Anand Kochukudy