“I measure the progress of a community by the degree of progress which women have achieved. – B R Ambedkar

More than a month has passed since the institutional murder of Payal Tadvi, a second-year MD student at Mumbai’s TN Topivala National Medical College (TNMC), hailing from the Tadvi Bhil Muslim community, a Scheduled Tribe. Tadvi’s case is the latest in the series of atrocities being perpetrated against Dalit, Bahujan and Tribal students in institutions of higher education across India.

Despite being the first such incident to gain nationwide attention post the advent of Modi 2.0, her death sadly failed to trigger nationwide protests, a la the wave of protests following the institutional murder of Rohith Vemula in January 2016. There are similarities on what ensued following the “institutional murder” (a term coined as part of the resistance movement) of Rohith Vemula and Payal Tadvi. In the case of the former, there were attempts to use technicality to try and establish that Rohith was not a Dalit—and, in the case of the latter, the so-called report sneakily confirms evidence of ragging but not the caste-related discrimination and humiliation.

The victim’s brother had stated that the perpetrators had the covert support of the hospital administration. This observation raises suspicion about the committee report denying the caste angle to it. To deny casteism, is by itself a casteist act.

Kerala too has had its history of tormenting Dalit Bahujans. Rajani S Anand had leapt to death from a building unable to cope with social exclusion and acute economic hardships in 2004. The case of Rajani S Anand in Kerala and Payal Tadvi in Mumbai reflect the plight of students hailing from an extremely marginalized background—the former had to discontinue her studies owing to her inability to pay the tuition fee.

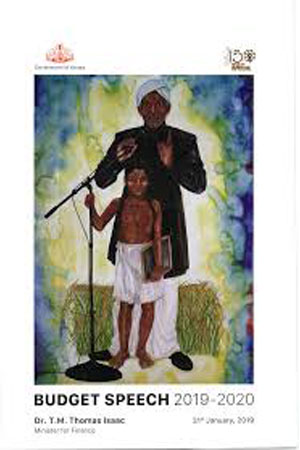

More than hundred years have passed since Panchami—the young dalit girl who accompanied Ayyankali after the historic school-entry struggle for the Dalits way back in the year 1914 in Travancore—epitomized emancipation. The story of Panchami is symbolic of the importance of women’s education in the social progress of a community and state. This year, a painting of Ayyankali leading Panchami to school adorned the Kerala State Budget cover, reinforcing the significance of the renaissance event. (This revolutionary act was witnessed almost half a century before the first African-American, six-year old Ruby Bridges, could desegregate the all-white William Frantz Elementary school in Louisiana, in the United States.)

More than hundred years have passed since Panchami—the young dalit girl who accompanied Ayyankali after the historic school-entry struggle for the Dalits way back in the year 1914 in Travancore—epitomized emancipation. The story of Panchami is symbolic of the importance of women’s education in the social progress of a community and state. This year, a painting of Ayyankali leading Panchami to school adorned the Kerala State Budget cover, reinforcing the significance of the renaissance event. (This revolutionary act was witnessed almost half a century before the first African-American, six-year old Ruby Bridges, could desegregate the all-white William Frantz Elementary school in Louisiana, in the United States.)

Panchami’s successful entry into the now Government UP School, Ooroottamblam, was achieved against tremendous backlash from the caste forces. It was blocked by upper castes and the school was razed to the ground. It had also led to caste revolts across the state of Travancore. Similar intimidation tactics are employed to put a cap on the endeavors of Dalit/Bahujan or Tribal students. Thus “Killing the Shambuka” is a phrase that reverberates from the mythical times to the contemporary.

Tadvi was an MBBS graduate from an extremely marginalized community and her death extinguishes a ray of hope. Since in this specific case, Tadvi is a woman and the perpetrators are women themselves, does raise some questions like:

(1) Has “annihilation of caste” ever become a feminist demand?

(2) Do contemporary feminist manifestos [like Why loiter?] have a subversive stand on caste other than identifying the violence in portraying working class, Muslim and Dalit men as sources of sexual danger?

Ambedkar had tremendous foresight in correlating women’s education with the annihilation of caste. He had resigned from Union Cabinet of Jawaharlal Nehru in protest against The Hindu Code Bill, an instrument which was inextricably crucial to women’s emancipation. He was of the opinion that, the education of women affected the annihilation of caste to a certain degree—since it can be argued that educated women tend to choose their life partners outside of their caste.

Ambedkar also felt that inter-caste weddings can annihilate caste—though there seems to be a gender disparity in these unlikely matrimonial alliances. This could be the reason why inter-caste relationships are opposed even by resorting to honor killings. Last year, in a clear case of honor killing, Kevin P Joseph, a Dalit Christian, was abducted and murdered by the relatives of his young wife, triggering statewide protests in its wake.

It will take a long time for such prejudice to wane from the mindsets of the people of India, whose brahmanical conditioning partitions the society vertically through a hierarchy. Women often become the “vectors” who transfer caste privilege from one generation to another—only education and organized protests can liberate us from the losses of many more Payal Tadvis.