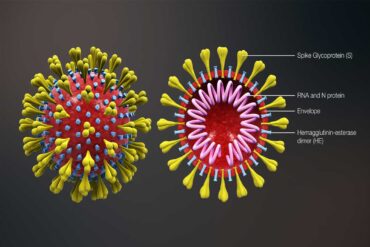

The ongoing Covid-19 pandemic caused by the corona virus has seen humanity skate on thin ice, with thousands falling ill and dying globally since December 2019. This crisis has had the world of letters discover a new term ‘Covidian’ which refers to the pandemic. I shall use that term for convenience sake, provided the high-priests of the literary world do not banish me to sackcloth and ashes.

Nations around the world, including India has upped their ante, staving off the pandemic shaping up to match the disastrous Spanish Flu, in terms of morbidity. The latter which lasted from the spring of 1918 until early summer of 1919 had infected 500 million—a third of world’s population at that time, and claimed 17 to 50 million, making it one of the deadliest pandemics in human history.

As Covid-19 rages on, has non-Covidian diseases and those suffering from them been neglected? Has the lockdown and restrictions posed by that inevitable measure resorted to by India adversely affected non-Covidian disease entities?

In India, from the outset when Covid-19 had begun to show evidence of breaking loose, treatment of the pandemic and efforts to limit its damages have been captained by the government. Public sector facilities had taken over the reins of that great responsibility of gargantuan proportions right from the very start. That is exactly why the southern Indian state of Kerala, blessed with a buoyant healthcare dispensation mechanism in the public sector had, at a time managed to flatten the viral curve, making Kerala the global flagbearer of the great human endeavor to tame the virus. To chain it, in fact. Before the global accolades died down and the bouquets the state received withered away, the viral curve stuck out its demoniac head once again due to the homecoming of the state’s citizens from other nations and Indian states.

As the country’s public sector grappled with the viral onslaught, the private sector took up the responsibility of tending to those suffering from non-Covidian ailments, especially lifestyle diseases like hypertension, and diabetes, and end-stage organ failure, and malignancy, all of which demand dedicated follow-up care, and adjuvant modalities like chemotherapy and radiation.

The private sector stood up to this demand with aplomb. Complicated procedures like organ transplantation and multiorgan resection for end-stage solid organ failure and malignancy respectively have been undertaken in the operating theatres of healthcare facilities in the private sector, which did not shy away from treating those involved in trauma. This came about with a great deal of personal sacrifice by healthcare workers at the time of the lockdown, where commuting to work had become an ordeal, for want of public transport and restriction clamped on movement. Not to say that the private sector had washed hands off controlling the pandemic, it chipped in too by offering facilities for viral testing and quarantining suspected cases. The disease itself had exposed healthcare providers across healthcare facilities to the danger of infection until it was made mandatory to test for the virus before patients underwent procedures within hospitals.

The lockdown had also reduced patient numbers approaching hospitals for non-emergency health needs, resulting in drastic fall in revenues especially in the private sector, leading to layoffs and drastic pay cuts. Two undesirable turnouts when healthcare workers continue to fight a dreaded pandemic with back to their walls, often without adequate PPEs to protect them.

That non-Covidian diseases have been adequately taken care of by the private sector has not come about cheaply. Treatment expenses have skyrocketed. Healthcare workers don expensive protective PPEs, and patients undergoing routine procedures need to be first tested for the virus, entailing higher treatment costs on patients.