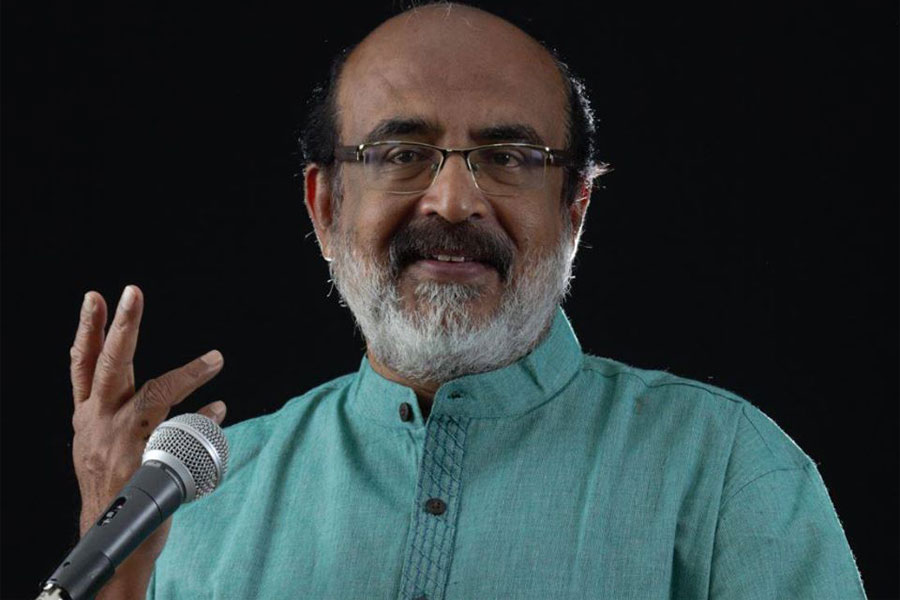

Finance Minister Thomas Isaac is under a triple lockdown. Like everyone else, he has been undergoing the effects of the national lockdown against Covid-19, enforced by the Modi government together with the state government, of which he is a part. The second lockdown is that of his treasury, which is running empty because there is no money coming in. The third and most crucial from a personal point of view is the lockdown on his role as finance minister.

In fact, even before the national lockdown against coronavirus was clamped down, Isaac has been largely unemployed as he has very little to do as finance minister. The scope of his intervention has been constrained by the limited nature of the resources at his command. His role has effectively been reduced to matching the bill for salary and pension payment for government employees with whatever is left in his treasury on a month to month basis. For want of anything more worthwhile to do, he has been engaging himself in Centre-bashing, attacking the stimulus packages of the Modi government and its policies towards the states.

Nearly all of what the Kerala government earns is spent on salaries and pensions. It is a different matter that such state welfare only covers 5 percent of the population. According to available data, Kerala has the highest per capita share of salaries and pension among all states. But the means for earning revenue are rather limited. Lottery and tax on liquor constitute two major revenue streams and the robustness of the treasury is inversely proportional to the moral degradation of the people. So the government feels good when people spend more on their booze and tend to gamble more, because it translates into more money in the state coffers.

But Covid-19 made all the calculations go awry. The lockdown ensured that there was nothing forthcoming from liquor and lottery as both activities had to be ceased. That in turn meant that Isaac had a real struggle to find money to pay salaries and pensions. The only option was to borrow, irrespective of the painfully high cost.

In April, he raised Rs 5,930 crore by selling state development bonds (SDLs) at exorbitantly high rates of 8.96 per cent, for which he faced flak from many quarters. Three bonds were auctioned with 10 years, 12 years and 15 years tenures respectively, each targeting Rs2,000 crore, at coupon rates of 7.91 per cent, 8.1 per cent and 8.96 per cent respectively. The rates were unusually high when compared to what other states managed to do—a neat 2 per cent lower.

This month, another Rs 1,000 crore worth of bonds were sold, but Isaac has had the satisfaction of striking a better deal this time: at coupon rates of 6.65 per cent and 5.09 per cent, similar to what the other state governments had sold their bonds at.

The state is now entitled to borrow only about Rs 6,500 crore more until November as per the arrangement made with the central government and RBI for 2020–21. But it is bound to hit another roadblock in the form of a ceiling of 3 per cent of the GDP that the Centre has set for it. That promises difficult days ahead for the Marxist finance minister, who often appears clad in bright-coloured kurtas, the trademark red being just one of the colours.

Isaac had to go red-faced when his version of what has come to be known popularly as the ‘salary challenge’ was shot down by the Kerala High Court. The ‘salary challenge’ was a term coined by Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan in the aftermath of the devastating floods of 2018, which called upon government employees to voluntarily forego one month’s salary as contribution to the Chief Minister’s Relief Fund.

With the fund dogged by allegations of misuse, the state government dropped the element of challenge from the plan for the Covid mobilisation and made it mandatory to deduct one month’s salary in six instalments. But much to the embarrassment of the state government, the court struck the order down as unconstitutional.

The state government had to then promulgate an ordinance to arm itself with the powers to defer up to 25 per cent of salaries of state government employees for six months during an emergency. This could yield up to Rs 25,000 crore for Isaac’s financial jugglery.

When trouble comes, it comes from all around. The heavy influx of Gulf returnees, most of them after losing their jobs due to lockdown in the wake of the heavy infection of Covid-19 in those countries, has added a new dimension to the problem at hand. This would mean that remittances, a vital driver of Kerala’s economy, would take a heavy hit. According to World Bank figures, Kerala receives Rs 1 trillion, which is estimated to fuel almost one-third of the Kerala’s gross state domestic product (GSDP). This is now expected to drop at least by 15 per cent due to the crisis. Also possible are large amounts of withdrawals from bank deposits held by NRIs, estimated at Rs 100,000 crore, further constraining the ability of the banks to support the state’s economy.

While on the one hand, the state government has to scale down its expectations on the remittance front, on the other, it has to weigh in the huge implications of some two lakh Gulf returnees joining the army of unemployed, tipping the social and economic balance of the state, which is already under strain. Under normal circumstances, the returnees could walk into the space left by migrant labour from north and east India, who have since returned to their home states, but their acquired new job profiles do not agree with the opportunities so created.

The state government has constituted an expert committee to assess the economic impact of Covid-19 pandemic on the state’s finances and suggest specific and significant additional revenue mobilisation measures to the help the state tide over the unprecedented challenges posed by the deadly virus.

The committee will seek to quantify the effect of additional expenditure obligations during the financial year 2020-21 on account of the recovery measures that must be initiated by the government. It will also make an assessment of the liquidity issues impacting the state’s treasury management.

The terms of reference of the committee include a detailed look at the loss to the own tax revenues (OTR) of the state in the immediate and short term and the likely projection of OTR collections for the financial year 2020-21. It will also analyse the impact of GST, Central transfers, especially tax devolution and non-tax revenue mobilisation of the state.

The state’s welfare economy masks the structural issues that mar the model of development being followed. Current expenditures like wages and salaries, subsidies and other transfers within the social and economic services have led to a consistent decline in the budgetary resources allotted for maintenance of capital assets and creation of new assets within such essential services.

Consequently, the state’s public finances suffer from continued high levels of fiscal and revenue deficits, low levels of public spending on capital works, utilisation of borrowed funds to finance revenue expenditure, mounting debt liabilities, higher interest payment burden and falling own revenue mobilisation efforts.

An analysis of composition of Kerala’s own tax revenue reveals that only a handful of tax handles contribute to public revenue mobilisation in any meaningful manner. These include sales tax/value added tax, state excise duties, motor vehicle tax, and stamps and registration fees. However, the huge drop in the share of state excise duties and stamps and registration fees in the own tax revenues over the years and in the recent past respectively has been causing serious concern. Further, there is negligible contribution by way of dividends and profits from state public sector enterprises and consistently falling contribution from economic and social services.

The government is in desperate need to reduce its salaries and pension burden and it has to generate more jobs in the private sector by creating an appropriate environment. Also, the practice of appointing large number of temporary staff, known by the name of contract employees, has to stop if the state is to make any headway with its fiscal regime. A recent review by Kerala State Finance Department found that around 30,000 excess posts have been created in various in various government departments, PSEs, corporations and 81 Boards, of which a majority are temporary employees.

The Pinaryai Vijayan government has not felt any inhibition on account of this precarious financial situation in its prodigal spending. Several instances of diversion of funds to buy luxury vehicles for ministers and officials and build glitzy bungalows for them have come to light. Crass cases of wasteful expenditures include hiring of high-cost lawyers to defend party workers accused of murder and other serious crimes.

Eyebrows were raised when the state government hired a special IT lawyer from Mumbai to appear in the case filed by Opposition Leader Ramesh Chennithala questioning the propriety of the state government entering into a deal with controversial US company Sprinklr for the analysis of data relating to coronavirus patients without the approval of the Cabinet or the knowledge of the law department.

Topping the list of shady deals is the controversial decision to hire a Pawan Hans helicopter for Rs 1.44 crore for 20 hours of flight time a month. The deal was justified in the name of disaster management missions and security operations. But there have been allegations of irregularities as a private company claimed that it had quoted a lower quote for the same aircraft.

The state government has also been accused to spending tax payers’ money to organise fancy global investors meetings, which produced nothing but hyperbole about the business-friendly environment in the state and no investments whatsoever.

Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan has been deflecting all criticism by fronting the success in the fight against Covid-19 and insisting that the growing intolerance of the Opposition parties is on account of their fear that people will credit the Left Democratic Front government for its achievements.