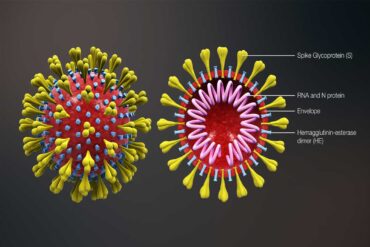

Those above sixty years of age are said to be particularly vulnerable to the coronavirus. So, the powers of the world have decided that the elderly should stay indoors and be safe. They shall go on living. No one asks: what for?

What if I do not want to go on living? Especially in a state that is tantamount to house detention. This, we are told, is for the good of the elderly. So, who decides what is good for them? Everyone other than the elderly. This is in keeping with the traditional notion that everything has to be decided, though not everything to be provided, for old people by those who are not old. Only those who are not old know what is good for those who are old.

A barely-concealed insult underlies this solicitude for the welfare of the elderly. It is assumed that for the elderly life is no more than mere existence, bare survival from day-to-day. Freedom of movement is irrelevant to them. The need to relate to the external world is superfluous. So also, companionship with others in their predicament. Three meals a day. A room in the house. The rest of the household busy with multitudinous preoccupations. In a world erected on busyness, where no one has time for anyone else. Stay cooped up in your room. Be safe. Go on living.

A few curious things are overlooked in this process. First, the elderly thus shut up in their homes still stay exposed. Other members of the household are moving in and out. They could bring the bug home. The reason this obvious thing is not considered is the assumption—not stated as such—that the elderly will stay ‘socially distanced’ from the rest of the family. So, a chasm develops between two generations: a corona-version of generation gap. The elderly need to be cut-off from their loved ones for their own sake.

One has to be monumentally ignorant about the plight of the elderly to assume that this is a favour done to them. Old age is the human condition in which all material frills of existence fall away and the core of life surfaces with its own needs. The fact that they are not met does not mean that they don’t exist. Foremost among such needs is the need to relate; especially to children. But children, like the elderly, are extra-vulnerable. So, they need to be especially protected from the elderly, who need to be protected from the rest of the family members. If this state is perpetrated, one thing becomes assuredly predictable: the elderly may survive the corona pandemic, but they will wither away for want of human nourishment. The blunt truth is that this is an atrocity on the elderly. It issues from cavalier callousness towards their plight.

The second strange thing is this: it is assumed that the elderly want to go on living. Really? I belong to this herd, if you like. Let me say this emphatically for myself. I would rather die than live in such a state for any period of time. I am a domesticated animal. I love the serenity of my home. My wife lends me such companionship as she can. I live mostly confined to a small corner of my house, comprising my bed-cum-study. But I need fresh air. I need to go and work in my small patch of a garden for a spell of time every day. This symbiotic relationship with nature is vital for me. The larger external world too is a necessity for me. Freedom of mobility is vital and indispensable, even if I am not smitten with wanderlust. Ask anyone who has any sense about it: movement is the essence of life. Short of this, the distinction between a living person and a living corpse tends to become notional.

Thirdly, there is a world of difference between voluntary self-quarantining and enforced home-confinement. The latter is coercive. What is coercive is oppressive. The good intention, if any, imputed to this arrangement is real only for those who theorize on it. It is hidden from those who perceive themselves as it fortuitous victims. The misappropriation of the unilateral right to decide what is good for me by agencies alien to me is unacceptable.

It is presumptuous on the part of any government—even of the Kerala government, which is the best in this respect in India—to assume that it can mitigate the oppression in which the elderly would be forced to live under such circumstances. No service agency can conjure up even illusory companionship. No articulation of good intention can substitute for a sense of existential vitality. No assurances can make up for lost mobility.

The COVID-19 pandemic confronts the elderly with the famine of alienation: alienation within one’s own home. Ironically, this famine will be felt less by the elderly who are living alone as couples or singly as widows or widowers. But it will sting the elderly living in homes, by erecting an iron curtain between them and the rest of the household, which is necessary if this home-confinement is to make any sense.

What matters to me at this stage of my life is not how long I live, but how vitally and meaningfully. The prevailing assumption that elderly need only to bide their time until death is a lie. Life still gurgles in the elderly. They crave to be active. To contribute. To be. A vegetative existence is unbearable. I see no sense in the prolongation of life in such a state.

I urge all concerned to re-think this situation, and to grant the elderly the same extent of freedom to decide for themselves that all else enjoy. The state has no duty, or right, to prolong my life. That is entirely my call. The affliction that stares the elderly in the face is the prospect of having to live—who knows for how long—as de facto prisoners in their own homes.

This is unacceptable. Avoidable. If it is deemed indispensable, then the most humane thing the state can do is to legalize euthanasia at the earliest.