Post the 2018 floods, Keralites see fishermen as superheroes without a cape. When the floods unpredictably hit the state, they didn’t hesitate to pull out their boats and rush to save lives. However, not many are aware of their hard lives. British artist Susan Beaulah’s paintings give a detailed account of their fast-changing lives. Her works emphasise on the marine phenomenon, Chakara, wherein fish converge in abundance in organically formed mudbanks. She is perhaps the first artist to paint Kerala’s fishers and Chakara exclusively.

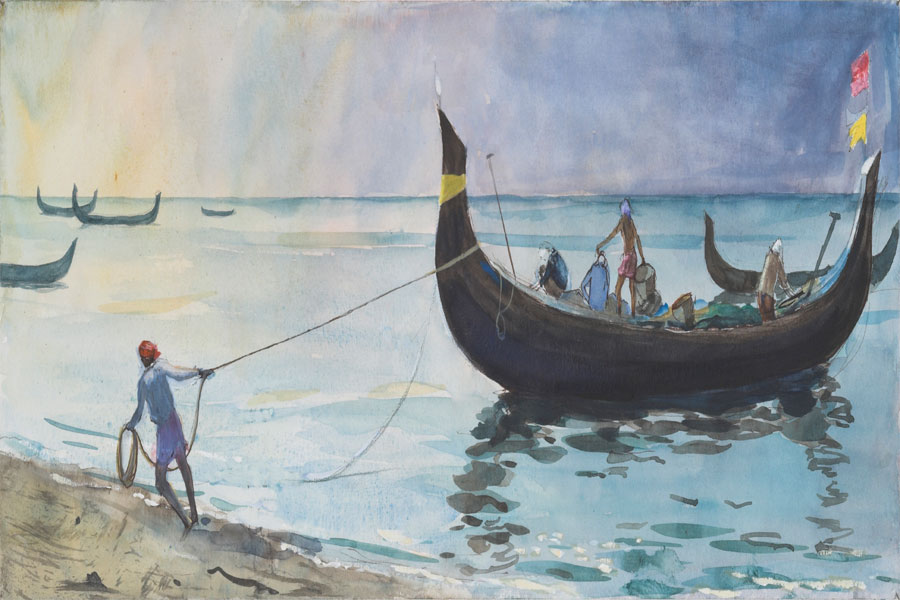

Having spent around a decade observing the fisherfolk in the coastal areas of Kerala, she knows a thing or two about them. She has captured their lives, mostly on the spot, on her canvas. The idea of painting fisherfolk hit Beaulah in 1990 during a residency in Kerala following her first painting trip to Rajasthan. “My idea was to paint women working in the fields, but then I saw a boat on the beach and was immediately captivated by its shape and elegance of line. It awoke in me a feeling of ancient times and of the Vikings invading the east coast of England over a 1000 years ago, using boats of remarkably similar design to those I was watching on this modern-day Kerala coast,” recalls Beaulah.

The vivid colours of lungis against the neutral colour of sand and the harmony of people working on the beaches and in the fields, at one with the landscape, caught her attention. “In the UK, figures in the landscape are of no interest to me as they appear to just pass through, detached and without that meaningful connection. I believe that a simple life, imbued with a sense of belonging is more real, has more integrity and is more beautiful to look at than a more commercially developed world.”

She returned to Kerala, in 2002, to paint those scenes that inspired her and realised those scenes were fading fast. She carefully chose a taxi driver who spoke excellent English, but he passed the job onto a colleague, Babu Bhaskaran, who had limited knowledge of English. “This man didn’t seem like the ideal companion at first. Later he told me he noticed my anger in the driver’s mirror of his old Ambassador!” However, over time, he picked up the language and became a great support. “Babu Bhaskaran and I then spent 10 days together searching the 600 kms of the Kerala coastline for boats to paint, but with very little success. We went further north till Mangalore in Karnataka. He proved a trusted and loyal assistant—and later friend—and never gave up when I asked him to travel the many, many small roads which led to the sea.”

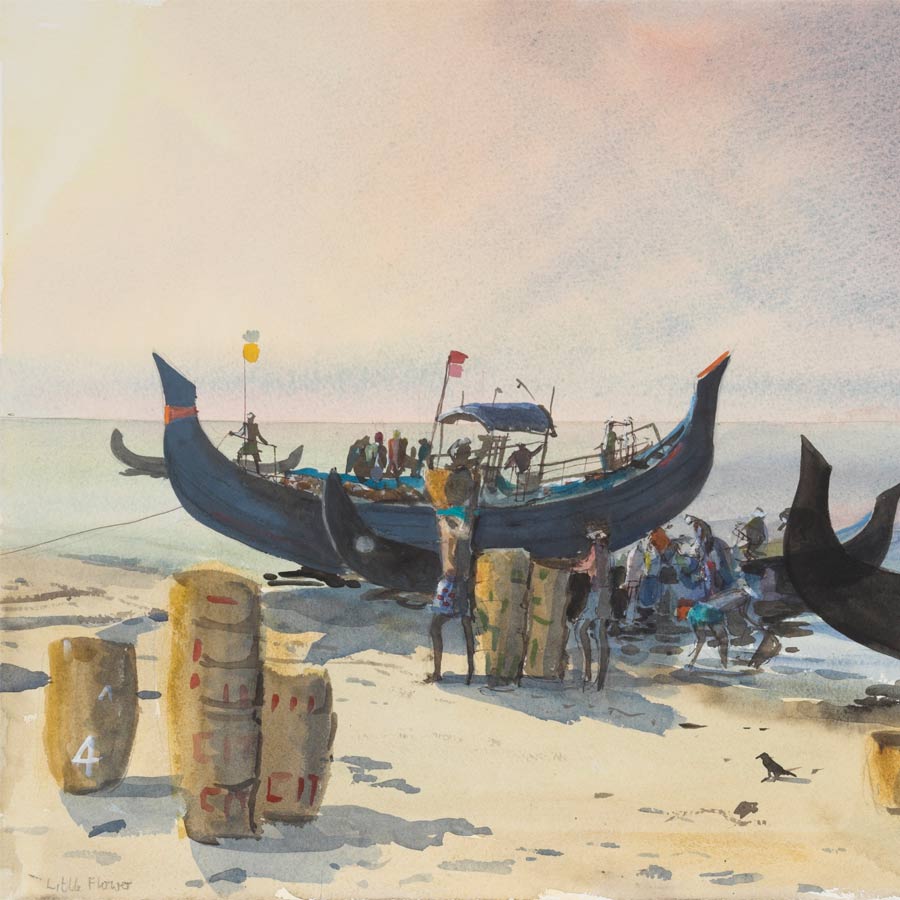

The search has never been easy. It was baffling and frustrating to find that villages which had been alive with fishing boats the previous season were now completely deserted. “When we did come across perfect subjects, the process was never easy. My first task was to find a shady place to sit in. We carried a beach umbrella, stool and easel which we set up amongst the squalor and stench that are characteristic of busy fishing beaches. It could be frightening—as a foreign woman—and I was always thankful for Babu’s loyal support: security man, driver, guide and artist’s assistant,” says Beaulah, who is often surrounded by fishermen while working. They would ask about her and, sometimes, make suggestions to her work. Beaulah says she was hence very conscious of every stroke that was done under a noisy audience’s scrutiny.

It was only after two years of this interaction that she first heard about Chakara. “Then things began to fall into place. The enormous scale of the adventure became apparent, and the elusive and mysterious nature of this phenomenon had me captivated,” she recalls. “No one can predict its bounty. It is a phenomenon which only happens here in Kerala and one place in South America.” Her paintings, about 100, carry the emotions Chakara brings to fishermen.

She does not hide her fear of losing this sight forever. “My observation, backed by the experts, is that with climate change and human intervention along the coast and backwaters, the Chakara is failing. It seems I have captured unique scenes which are now sadly lost to us—and would soon have become a forgotten thing of the past,” says Beaulah. “I would estimate that over 95 per cent of my painting is done on the spot, outdoors. I am not inspired by a flat-coloured-ink-on-paper photograph—I like real life. When painting the Chakara I worked almost exclusively from the shore.”

Her day would begin with a wake-up call at 5.30 am. “We would set off in the taxi to drive maybe 20 kms to the Chakara beach where I would walk about with a small sketchbook looking for a subject and then sketch out the idea. I would call Babu to help set up my easel and then choose a size of paper to reflect the scene I was about to paint,” says Beaulah.

Mostly, the subject would be rapidly moving figures of people at work. She would compose the work using a light-fast, thin artists pen. “Often, I would only have time to draw just a part of each figure and have to come back later to sketch in the rest. I would start to paint the background first, gradually working up the scene over 3 to 4 hours. If the subject was more landscape-based, I would start with all-over watercolour washes to capture the light and the atmosphere, allowing each colour wash to dry before applying the next. The inevitable crowd of boisterous onlookers always made demands— asking me to add the names of the boats, the colours of the flags, the lungis etc. I felt a need to balance what I wanted to paint with the need to appease the fishermen. After all, I needed their co-operation. Each painting became a symbiosis between the ideas and eye of the artist and those of the group. This interaction was as much as part of the finished painting as my original sketch had been.”

Beaulah uses watercolour as she feels it is an ideal medium for depicting water and light. “The luminosity of watercolour paints gives a quality to the painting which simulates the feeling of floating, of the fleeting light of sky on water, and the subtlety of the reflections. I developed a way of working at speed to capture the moving figures and boats coming onto the shore. The process always remained a huge challenge and this kept me interested,” explains the artist, a native of Yorkshire, England.

After graduating from Hull Regional College of Art, she worked as an art teacher in London, and became a full-time professional painter in 1988, with numerous commissions and exhibitions in the UK, Europe, the USA and India. “I recently returned to East Yorkshire from London, to live and work. In 2002, I started to spend every winter painting in Kerala. Closely observing the daily life around me, I have tried to create a unique record of a way of life which is fast disappearing,” says Beaulah, who believes in the power of visual storytelling. “I observe the natural world around me, ideas for paintings just come into my head.”

An exhibition of her works was recently held at the David Hall Art Gallery in Fort Kochi. She was overwhelmed by the positive response. “Everyone seemed genuinely open to and appreciative of my work which depicts such familiar every-day scenes, ones that they may well have taken for granted. I sensed an appreciation that a foreigner should find such delight and inspiration in their landscapes, people and culture. Their attitude to art is enlightened, curious and serious,” concludes Beaulah, dreaming of associating with the Kochi Muziris Biennale in 2020.