The suits filed by the state governments of Kerala and Chhattisgarh in the Supreme Court, challenging the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the National Investigations Agency (NIA) Act respectively, appear to be too ambitious to produce the results that they desire.

In any case, both petitions are more in the nature of political posturing by the ruling parties that lead the government in both the states rather than a legal challenge.

A three-member bench of the Supreme Court has already taken up for hearing 130 petitions challenging CAA on the plea that it violates the fundamental rights of the citizens enshrined in the Constitution. The Kerala petition is different from these in that it challenges the power of Parliament to enact the controversial law. The Chhattisgarh government’s suit also challenges the power of the central government, though in a different field. Both petitions have been moved under the provisions of Article 131 of the Constitution, which deals with centre-state disputes.

On first sight, there is nothing wrong with both petitions as there have been several instances in the past when the central government had been challenged under Article 131. So, there should not be a problem with the maintainability of the suits. But it is perhaps for the first time that a challenge has been raised against the power of parliament to enact laws, though it does not seem to be destined to achieve success.

Such instances in the past mostly involved subjects where the state government concerned had a reason to get agitated about their impact on the state per se and therefore had locus standi. But the prayers in both suites exceed their domain as the issues raised are more national in nature rather than provincial.

In simple terms, the crux of the Chhattisgarh argument is that the NIA Act creates a ‘national’ police, which under the division of powers between the centre and the states is a state subject. However, post-Independence experience with issues such as terrorism has shown that there may be situations where solutions lie beyond the responsibility of any state or group of states, warranting effective central intervention. In such cases, the role of the centre becomes unquestionable.

There is no immediate provocation for the Congress government in Chhattisgarh to move the court other than to build up pressure on the Modi government in the wake of the widespread agitation against the new citizenship law. Fighting terror is as much a concern for the state as it is for the centre, and a conflict of interests in this respect can only be seen as political.

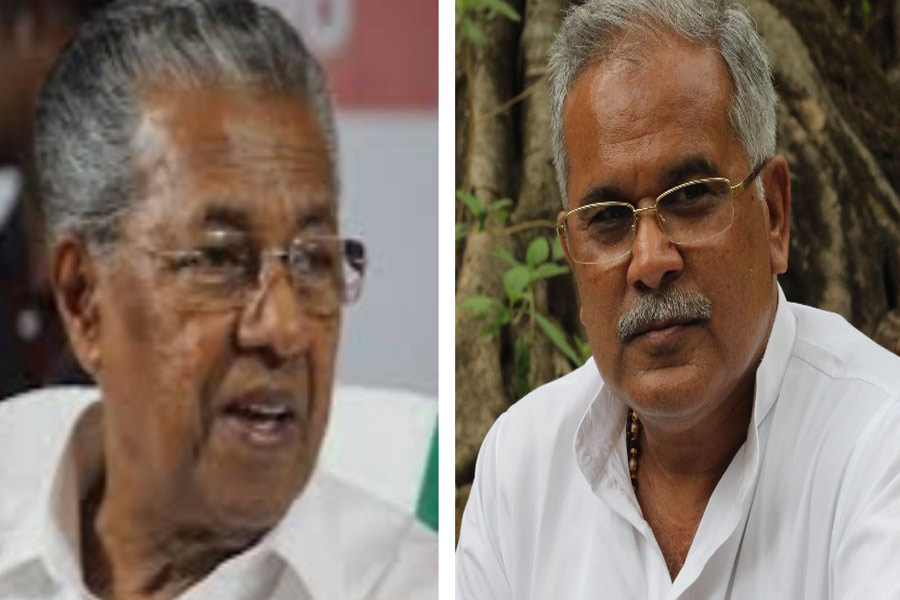

The Kerala petition is even more curious, although it can be seen as part of grandstanding by the Pinarayi Vijayan-led Left Democratic Front (LDF) government against the CAA. In fact, Kerala has been in the forefront of the anti-CAA campaign, with the state assembly passing a resolution calling upon the Modi government to scrap the law. This even inspired some other opposition-ruled states, including Punjab, to follow suit.

The Supreme Court move by the state government is indicative of Chief Minister, Pinarayi Vijayan’s ambition to emerge as a national champion in the fight against CAA. He was the first opposition Chief Minister to declare that the new act will not be implemented in his state.

The action by the Kerala government has, in fact, led to a flash point between Governor, Arif Mohammed Khan and the state government, with the former insisting that the government violated the rules of procedure by failing to inform the Governor as head of state about the move to approach the Supreme Court against the new citizenship law. Khan is holding firm, despite conciliatory gestures by the government. He insists that the mistake will be corrected only by the state government withdrawing its suit.

Apart from scoring political points, it is, however, difficult to see the Kerala government prayer to the court to strike down CAA going any distance. The plaint argues that the law violates the provisions of the Constitution and is in breach of the fundamental rights of the ‘inhabitants of the state’. While the Muslim minority angle in the argument is obvious, there is nothing in the new law that applies specifically to Kerala as opposed to other states. So it does not give any pre-eminence to the state to claim grievance.

By Arrangement with IPA