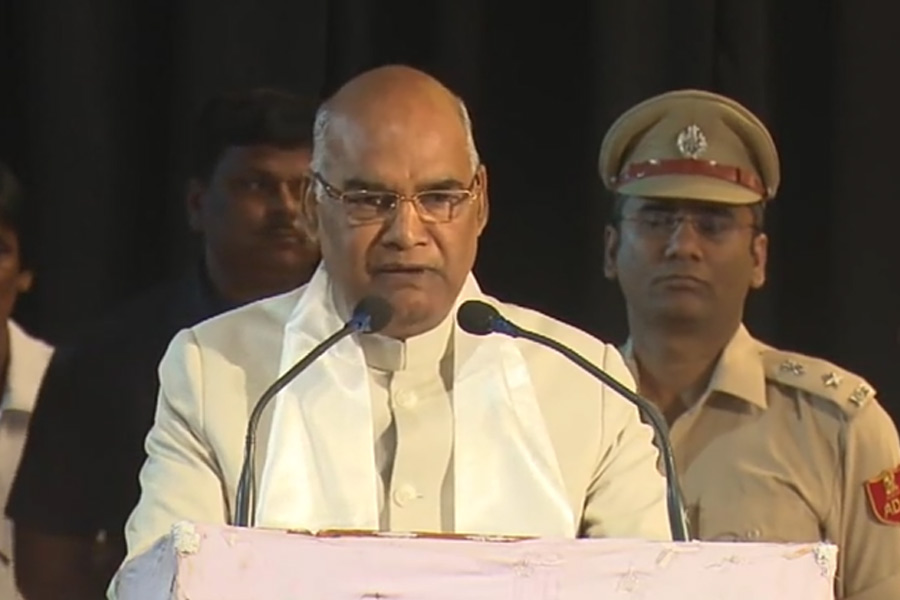

On December 6, 2019, the President of India, Ram Nath Kovind, while addressing the National Convention on Empowerment of Women for Social Transformation, stated that “Rape convicts under (the) POCSO Act (The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012) should not have the right to file (a) mercy petition”. In all probability, this statement came in the backdrop of the public outrage against the recent cases of rape and murder that have again shaken the collective conscience of the country and re-awakened the wound of the Delhi rape case. India witnessed two grave atrocities against women within a period of one week—the Hyderabad and the Unnao rape cases, where both brutalities ended with the victims being charred to death by the alleged culprits.

At a time when the whole nation is engrossed in deliberating a possible solution to such atrocities, the role of national leaders becomes very crucial: it is their duty to guide popular opinion in the right direction. Running high on emotions, the spirit of vengeance is likely to blindside the public of the possible consequences that would prevail if proper “due process of the law” is not followed to seek justice. Therefore, in such critical times, the President’s assertion that a plausible solution to this deep-rooted problem lies in deviating from the fundamental principles of criminal justice and depriving a category of culprits of their fundamental rights is quite simply regressive.

Along with other powers, Article 72 of the Indian Constitution allows the President, the power to grant pardon, reprieve etc. to any person convicted of any offence where the sentence is a sentence of the death penalty. It is an executive function where the President acts upon a mercy petition submitted by an accused or by anyone known to them. The President is required to act upon the advice of the Council of Ministers which is conveyed to the President through the Ministry of Home Affairs. There are no formal guidelines or grounds upon which the pardon is required to be granted, however, the philosophy underlying the power of pardon was well illustrated by the American Judge William Howard Taft in Ex Parte Grossman where he stated that “Executive clemency exists to afford relief under harshness and evident mistake in the operation or enforcement of the criminal law. The administration of justice by the courts is not necessarily always wise or certainly considerate of circumstances which may properly mitigate the guilt”. Accordingly, the factors that are generally taken into consideration while deciding on a mercy petition are mental fitness, a long delay in investigation and trial, an inadvertent error by the court etc.

The significance of a mercy petition in criminal jurisprudence was well asserted by the apex court in Shatrugan Chauhan v Union of India where it stated that “mercy jurisprudence is the evolving standard of decency, which is the hallmark of society”. Also, the pardoning power of the President “is a constitutional obligation, not a mere prerogative” and “the right to seek mercy…is a constitutional right and not at the discretion or whims of the executive.” This case provides enough protection to the accused under the POCSO Act from the changes that the President is recommending.

Besides this, the principle that seeking mercy is a right, not a privilege can also be found well ingrained in our fundamental rights. Under Art 14 of the Constitution, the State shall not deny any person equality before the law and equal protection of the law. The bare text of this article makes it amply clear that the right to seek mercy cannot be made offence-specific. Such categorization will not withstand the test of intelligible differentia. It would be extremely irrational to argue that if a person is given the death sentence for murder then there is a possibility of error in judgment and hence the right to seek mercy shall be granted, however, the same possibility and right shall be ignored when the accused is given the death sentence under the POCSO Act.

Furthermore, under Article 21 of the Constitution, no person shall be deprived of their life or personal liberty except according to the procedure established by law. Although by giving a wide ambit to ‘life’ and ‘personal liberty’, the apex court has made Article 21 an inexhaustible source of many rights, the right to seek mercy is again, of such a kind that it is directly attributable to the bare text of the article. The death penalty is a direct contravention of Article 21; hence, its final execution has to take place without any degree of deviation from the procedure established.

Currently, the procedure established by law grants the right to seek mercy to every individual and deprivation of this right to the accused under the POCSO Act would cause a complete deviation from the prescribed procedure. Moreover, the Maneka Gandhi Case has extended the application of the principle of reasonableness under Article 14 to the nature and requirement of procedure under Art 21, hence, every procedure has to be “right, just and fair”. Therefore, if the legislation was to try and create an exception to Article 72(1)(c) for the accused under the POCSO Act, such separate procedure would not pass the test of reasonableness because there are no substantial grounds available to justify the classification and deprive a specific category of accused their right to live by cutting short their remedies.

Article 39A imposes the responsibility on the state to provide equal justice and free legal aid to the accused persons and it is read in conjunction with Article 21 because the right to free legal aid is also a part of a fair, just and reasonable procedure. Accordingly, in the case of Shatrugan Chauhan v Union of India, the court has reiterated that the responsibility of the state to provide free legal aid to convicts on death row must also be extended to cover their cases of mercy before the President. Any attempt of the state to deprive certain convicts on death row of their right to seek mercy would, therefore, be incomplete contravention of its duty enshrined under Article 39A.

There was no doubt in the minds of the Constitution-makers about whether the President should have the pardoning power or not. During a discussion in the Constituent Assembly on this aspect, N. Gopalaswami Ayyangar said unequivocally, “we are setting up a Head of the Federation and calling him the President, one of the powers that should almost automatically be vested in him is the power of pardon”. The intent was to repose the power of the people in the highest dignitary; however, with great power comes great responsibility. It is not a matter of grace or privilege but an important constitutional responsibility which needs to be exercised in the aid of justice and not in defiance of it.

President Kovind’s statement is not only in defiance of his constitutional duty but it also shows a total disregard of the principles of justice that are enshrined in the Constitution of India. The President of India has the power to mould public opinion, but he also has the responsibility to use his influence wisely. If under sensitive circumstances, he makes statements that are devoid of constitutional understanding and are aligned with the public emotions, the repercussions will be dire. Such statements will only solidify layperson’s belief that criminals do not have fundamental rights, retribution is the ultimate goal of a criminal justice system and the right to seek mercy is a privilege which can be taken away at will. Indirectly, the President will end up portraying a false picture of our Constitutional framework.

By Arrangement with IPA/The Leaflet