Spoiler Alert: Some scenes are discussed in detail

It’s not that I go to the movies with pre-conceived notions but in this instance, I was assured it was a romcom—so I let my guard down, all ready to laugh at the inanities that would delightfully lace a Malayalam film in that genre. The film does wander around in that zone till half-time and then takes a wrong turn.

Sleevachan (Asif Ali), 34, is a bachelor living in the Idukki High Ranges. He is a busy farmer with special interest in cultivating a certain variety of pepper and besides, he runs a DTP/Photostat shop in town. He finally decides to get married not because he needs companionship but his mother needs that more.

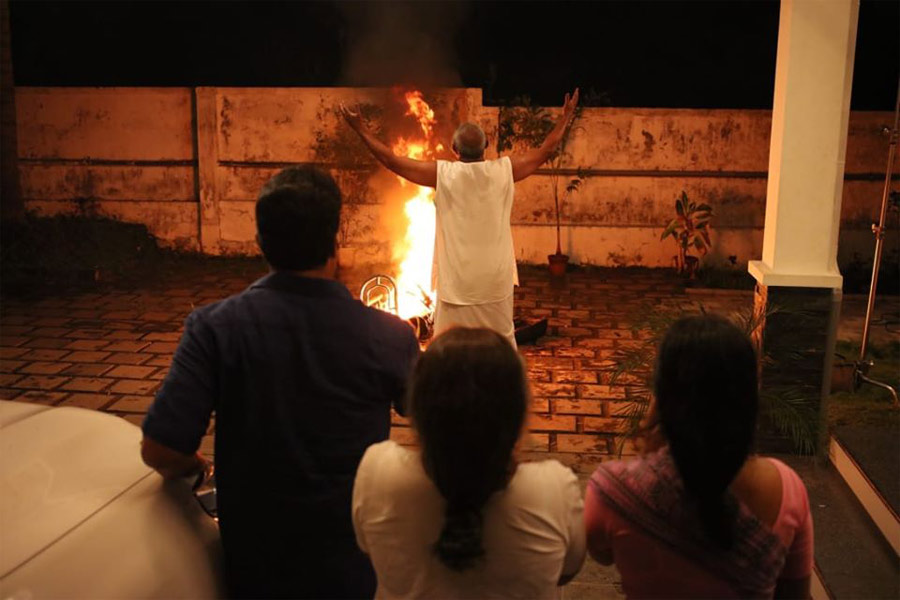

He’s the youngest kid, coddled by four sisters and a doting mother. It has all the makings of a rural patriarchal family. Pardon me reader, not for a single moment did I think it was a dysfunctional one though it seemed like a seriously boring family. Sleevachen is the quintessential ‘good boy’ who has never looked at a girl in his life and he has never ever had any “impure thoughts”. He even goes to a confessional about his pure mind.

The local broker finds the perfect match for Sleevachan, Rincy (Veena Nandhakumar), the niece of the parish priest. During the pennukannal—roughly translated as ‘sizing up the girl’—the custom allows the boy’s family to measure the girl’s height, colour and even the length of her hair, (It’s quite like how one would gauge the dimensions of a car or some other inanimate object that one is about to buy). Sleevachan skips the-all-important-few-moments-alone-with-the-girl and instead asks to meet her invalid mother and dishes out some advice. That is so-sweet and so-endearing a moment that the girl immediately gives her consent with nary a word spoken between them. What is to stop the wedding to follow in the next scene?

The trouble begins soon after. This innocent, rural bloke, who, ironically hails from a state which consumes ample amount of pornography and loves porn stars in equal measure, has no clue how to go about his sex life. He breaks out into a cold sweat when he thinks about it. Even his assistant is pretty savvy about how to woo women but Sleevachen has no one to advise him. Moreover, he doesn’t have a smart phone to check things out on the net either. For crying out loud, he seems to have missed out on how the fowl and cattle on his estate mate—the poor fellow must have closed his eyes.

The first night is a disaster, so is the honeymoon. The men about town want to know the details but Sleevachen has nothing to share. This ‘good boy’ who is clueless about what to do with his wife avoids making love to her. A week or so later, Rincy confronts him as to why he seems to be avoiding her but he shrugs it off saying he’s too busy. Finally he picks up guts and to prove his manhood, downs some liquor and pounces on her. She clearly does not give her consent. The muscular act demonstrates that he believes the woman’s body is his to posses and primarily for his pleasure. A belief that runs deep in our patriarchal society. From then on the film ceases to be funny and it’s on a downward spiral.

Sleevachen knocks Rincy unconscious and she is rushed to the hospital. She survives his bestial appetite and sexual violence. It would have been far more interesting if she had died on him and that would have shaken the audience too. But here, in a calibrated manner, it is revealed to the audience what transpired that night was marital rape.

Sleevachen’s mother’s reaction on seeing the unconscious Rincy is mild, she just slaps him ever so slightly when Sleevachen says he has no clue what he has done. Though the family does the right thing by rushing her to the hospital, the sisters seem more embarrassed about what people would say about their brother, playing out the scenes in jest thus diminishing the gravity of the issue.

The doctor plays a crucial role when she summons Sleevachen and gives him an earful. She threatens to call the police and report the matter. However, on the intervention of his mother and the parish priest, Sleevachen is let off. It’s astounding that the doctor does not call her family and ask that she be taken back home. The doctor signs the discharge certificate and sends the rape survivor back to her husband’s family which makes it problematic. And neither of them is sent for psychiatric counselling.

The normalization of marital rape is all too established in India—law makers to godmen have said that marital rape is not a crime. The Indian government’s position on marital rape is that criminalization of marital rape would destabilize society. The filmmakers had an opportunity to take a different stand and drive home a point but they chose to make light of the issue. They chose to save the institution of marriage. They explored a novel idea but they did so flippantly, with no focus on the post-trauma and the humiliation that Rincy must have experienced.

Rincy is taken to her husband’s home and there begins the normalization of Sleevachen’s attack. The huge wounds on her lips and her neck suggest deeper wounds in her private parts that make the deed reprehensible. The family keeps harping, so does the priest, on Sleevachen’s innocence. The viewer is lulled into believing that all is fine when it is not. This is a technique that has been used before in a couple of films which has rape as its central theme.

We have seen that in the 1984 Malayalam film, Ente Upasana, where the protagonist, Arjunan (Mammootty), rapes Lathika (Suhasini), who is happily engaged to someone else. There’s soothing music, a precursor to the rape scene and, during the rape, the music races briefly and the falling rain gives the wrong aural cues disengaging the viewer from the horror of the scene. Likewise the Oscar-winning 2016 Iranian film, The Salesman, plays on the viewer’s sympathy when it becomes evident an old man is the rapist. These films seek to deflect the audience attention and soften the criminal nature of the act.

The priest comforts Sleevachen and so does his mother. Sleevachen’s mother asks Rincy for forgiveness but she is quick to add that he had made a mistake and Rincy should just forget about it. Rape, marital or otherwise, is not a mistake and should not be showcased as such. There are other scenes, obliquely dismissing marital rape as a common occurrence. Strangely, it is the women who advice Sleevachen to not worry too much about what he has done. The film seems to underscore the patriarchal view that it’s a woman’s lot to adjust. The only redeeming scene in the film is when Sleevachen begs Rincy for forgiveness. But was it necessary to whitewash Sleevachen to get to that moment?