The tale has been told time and again. An ordinary act turning into collective action of the masses and spreading rapidly through a large population on their Social Networks. But, contrary to popular millennial opinions, ‘Virality’, which is usually considered to be a modern-day digital çonstruct, a natural progression in a digitally connected society, is challenged by a little known 16th-century German friar, Martin Luther.

More than five hundred years ago, on October 31, 1517, a humble German friar Martin Luther challenged the Catholic Church with his ‘Ninety-five Theses’, which he posted on the door of the Schlosskirche (Castle Church) in Wittenberg. This event not only came to be considered the beginning of the Protestant Reformation in Christianity, but it also marks the beginning of a culture of tagging and posting on the walls—literally.

Within two weeks, Martin Luthar was a viral sensation; his message had already spread all over Germany and in entire Western Europe in the following weeks. It was, perhaps, a first of its kind viral campaign in human history, sans the Internet.

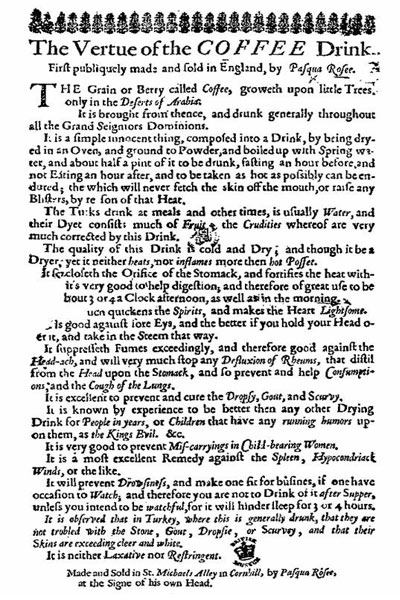

1517 Nuremberg printing of the Ninety-five Theses. Source: Berlin State Library.

1517 Nuremberg printing of the Ninety-five Theses. Source: Berlin State Library.

The Internet of the time—Printing Press, a newly introduced contraption, paved the way for this grand success of Luther’s message in such a short span of time. Hundreds of pamphlets were reprinted (16th-century version of Retweets) throughout Europe. All thanks to this new, marvelous, cheap and subtle art, the art of printing. As with the Arab Spring and many other Social Media phenomenons that scholars of the day call “collective action” in the Social Media context, Luther showed us how a new media could change the world order centuries ago.

Truth to be told, the idea of interconnected communities in a distributed network is not a uniquely digital phenomenon. Modern-day social media influencers and viral celebrities are perhaps, heirs to this rich tradition that began with the Romans and later, brewed in the 17th Century London Coffeehouses.

The Arrival of Coffee in Europe

The story of Coffee is a rather poignant tale—a ‘Muslim Drink’, popular among Arab mystics, going global. It spread to Europe in the early 17th century through trade and European travellers to the Ottoman Empire, who brought back the stories of a dark black beverage. Legend has it, when Coffee first came to Venice in 1615, the local clergy called it “bitter invention of Satan” and, asked Pope Clement VIII to ban it, denouncing it as an act of Satan. He, however, to everyone’s surprise, decided to taste the beverage before making any decision and found it so satisfying that he ended up ‘baptizing’ the beverage.

In 1647, the first coffee house came up in Venice, starting a wave of Çoffee House phenomenon, which spread throughout Europe in a short span of time. The first coffeehouse in England was opened in Oxford in 1652—a building on the same site now houses a café-bar called The Grand Cafe.

Within a few years, there were more than 300 coffee houses in London, where people gathered to drink coffee, learn the news of the day, and discuss matters such as politics, scandals, gossip, fashion, and current events. These Coffee houses broke the prevailing class system and encouraged men from all professions to join in the caffeine-fueled debates, which were the main feature of coffee houses.

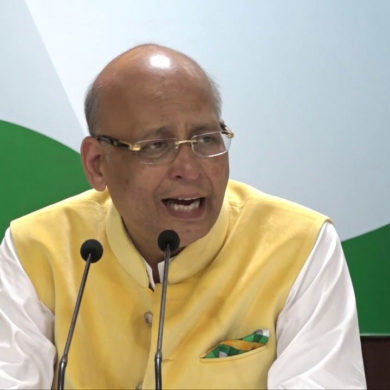

A handbill published in 1652 to promote the launch of Pasqua Rosée’s coffeehouse. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The concept of a coffeehouse was an innovation that emerged and served as centers for learning and news culture, as they clubbed news and coffee together to attract customers. Much like today’s Social Media, these Coffee houses served not only as a platform to debate and network, they also served as a prime source of news, gossips and of course, misinformation.

The democratization of debate culture, where you can end up sitting next to a scientist or a philosopher, was a revolutionary idea for 17th century Europe, and it proved to be a catalyst for creativity and innovation during Enlightenment Era. One of the foundational works of modern science is a result of a coffee house argument. Author Tom Standagein his book Writing on the Wall: Social Media—The First 2,000 Years, notes that “it was a coffeehouse argument among several fellow scientists that spurred Isaac Newton to write his Principia Mathematica.

These 17th-century networking hubs were a key source of new scientific acumen, knowledge, and wisdom, and they were rightly termed “Penny Universities” because you just had to pay a Penny as a cover charge for an endless supply of coffee and high-quality curated content. In direct contrast with their modern-day successor, the proverbial “WhatsApp University”, coffee houses provided a culture of reasoned debate and articulated information sharing.

Social Media & Participatory Culture

Philosophers, poets, merchants, traders and political groups frequently used coffeehouses as meeting places, and slowly, specialized coffee houses began to appear. The theme of the coffee house would determine the type of person you’d likely encounter. It was the first of its kind personalization of content of sorts.

Jonathan’s Coffee-House, a significant meeting place to post the prices of stocks and commodities, eventually became the London Stock Exchange. Lloyd’s Coffee House, opened by Edward Lloyd on Tower Street in 1686, a popular place for sailors, merchants, and shipowners became Lloyd’s of London. Long before modern-day Social Media giants turned the idea of Social Networking into a profitable venture, 17th-century coffee houses had already pioneered the game. Facebook et al are late arrivals.

But, with great power, comes great responsibility, as Spiderman tells us, and the growing clout of coffee houses and the part they played in shaping public and political opinions didn’t go well with the government of the day—and for obvious reasons. King Charles II of England issued a proclamation to end the legality of coffeehouses in 1675. He proclaimed that these coffee houses promote idleness and rumour-mongering. Several hundred years later, it still remains the most quoted justification for today’s internet censorship by the governments of the day. As Scottish Enlightenment Era writer-philosopher David Hume put it, “Mankind are so much the same, in all times and places that history informs us of nothing new or strange in this particular”.

The ideas that govern our modern-day Social Media ecosystem, it turns out, were first put to the test in 17th-century coffee houses of London. Perhaps, history’s chief use is only to discover the universal principles of human nature, which transcends time and space.

Ever since the word Coffee entered the English language from Turkish ‘kahve’ in the late 16th Century, this newfangled, abominable and heathenish liquor called coffee has been brewing revolutions, cutting across networks, cultures and millenniums.

Cover Image: Wikimedia Commons