The last edition of the Kochi Muziris Biennale (KMB) was fraught with an existential crisis, when an accusation of sexual harassment was raised against Riyas Komu, one of the founders of the biennale. The charges were not officially brought out, but posted on an anonymous Instagram handle. Komu rightly and immediately stepped down from all the managerial positions of the KMB. The demons of sexual harassment charges have now been laid to rest.

In a development unrelated to the Biennale, Subodh Gupta, the superstar of Indian contemporary art field, also called the ‘Damien Hirst of Delhi’, has initiated defamation proceedings this week against the same Instagram handle that had brought out sexual harassment charges against him (along with Komu).

Despite the presence of Guerrilla Girls, a feminist art collective that fights gender inequality in the art world, and a feminist curator in Anita Dubey, the Kochi Muziris Biennale in its last edition failed to invoke the erstwhile matrilineal spirit of the locale, or succeed in exposing the rotten patriarchal power culture at the centre of the contemporary art world. During the showpiece presentation by Guerilla Girls, a noted art critic and writer from Goa boldly stood up and spoke on the gender hierarchy and power relationships prevalent in the biennale and received support of the audience, most of whom stood with her.

Even cynics and rabble rousers have identified the biennale as a possible source of future social change in Kerala. In that respect, it is a harbinger of an egalitarian future. The biennale is a promise that such hopes shall not be belied. With the second consecutive woman curator for the KMB 2020, Shubigi Rao, the latent forces of patriarchy have mobilized themselves and comments are already being made of her femininity rather than the quality of her art. This needs to be immediately addressed.

Vipin Danurdharan’s Sahodarar, inspired by Sahodaran Ayyappan, the leader of Kerala Renaissance, was the major emancipatory work in the latest edition of the Biennale that captured the Malayali political imagination in a big way. Not only did the art work challenge recidivist tendencies in “progressive” Kerala, the way the teeming masses of humanity in Fort Kochi were incorporated into the work redefined conventional notions of art itself. The biennale establishment was particular in adding a local flavour to the event.

Most Malayali social fantasies were catered to, among them the Malayali’s love of mass events, cinema, food culture, left-wing progressivism, mutual coexistence, syncretism, sense of cooperation, and the like. But the rich vein of matrilineal traditions that run deep in Kerala society, in its art forms like Theyyam and in hereditary practices—norms of inheriting property and in kinship relations—were not catered to.

The high human development indices—in infant mortality, female education, literacy and the positive female to male sex ratio—are often, rightly or wrongly, attributed to the matrilineal tradition of Kerala. Rather than turning it into a cliché, the Biennale has the potential to invoke this dormant lode in the social consciousness of Kerala and to turn it into a potent tool for social mobilization around gender identity.

The subaltern resistance movements, the scale of ecological degradation and the resultant upheaval in society undergoing churning, have to be honestly reflected in the contemporary art of present day Kerala. The attempt to push Kerala as a global tourist location and to harness the energies of the Biennale for the same is an urgent requirement.

The innate nativist sensibilities of Kerala and Fort Kochi have so far proven a bulwark against sexism, racism and religious fundamentalism. The acknowledgement of such traditions of artistic resistance, from the Bhakti poets (Cheeraman, Ezhuthachan, Poonthanam, Cherusseri et al) onwards has to go beyond mere officious gestures of self-congratulation and be incorporated into the Biennale.

The Kochi Muziris Biennale as a template set for the artistic renaissance of Kerala has rightly steered clear of an elitist, traditionalist current provided by Raja Ravi Varma and the masters of the past including KCS Panikker. But the gendered nature of much of the hullaballoo surrounding the biannual art event leaves one desiring for more inclusivity in terms of the subaltern maternal crafting of Kerala society itself.

The Biennale and its cutting-edge perspectives can contribute to the development of a new sensibility that can alter the very nature of lived reality in Kerala. But organizational nightmares and the politically suspect stances of the event owners—including sponsorship providers—can possibly lead to a diminishing of such promise.

The base-superstructure dichotomy proposed by Marx, which posits the political economy as the foundation for the wider cultural sphere, finds few takers in the changed cultural scenario imbued with identity politics. But revisionist Marxists has proposed the idea that the cultural superstructure is primary in its ability to craft the base itself. Thus forms of art and literature have acquired an emancipatory potential in Marxist circles. It is this current that is being channelized through valorisation of the possibilities held by the Biennale among the left-wing.

In order to minimise this toxic degeneracy from creeping into the echelons of government funded art in Kerala, the base itself, consisting of alternate kinship systems and family structures and economic inheritance patterns has to be revived and replenished. The synergy between lived reality and artistic forms of expression, in the age of virtual reality and internet, requires radicalism, tradition as well as alternate possibilities. These together alone can provide access to a rich vein of untapped resources lying hidden in the collective Malayali unconscious.

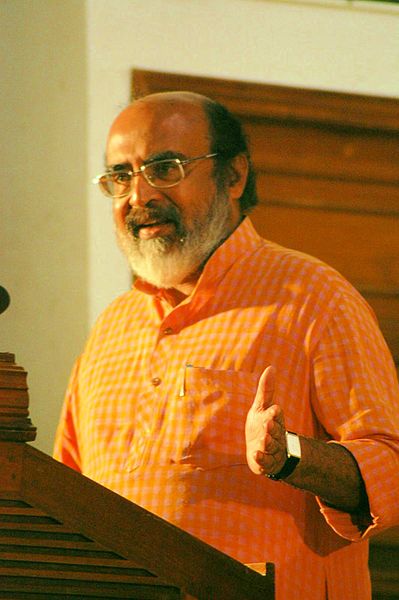

Cover Image credit: Minu Ittyipe