Veteran Gandhian Thayatt Balan, now aged 92, had his first encounter with history at the age of six. He travelled on the shoulders of his father who walked from their home in Panoor to the Thalassery beach, where Mahatma Gandhi addressed a huge gathering in 1934. The image of Gandhiji, sitting cross-legged atop a raised platform, still remains etched in his mind. Gandhiji was on his fourth visit to the land of the Malayalis, his first visit being in 1920 during the Khilafat-Non Cooperation movement.

Gandhiji’s first visit was political, and on the occasion he was accompanied by Maulana Shoukat Ali, one of the top leaders of the movement demanding restoration of the Turkey Sultanate, as the sultan was venerated as the global leader of Islam those days. In Malabar, the Khilafat Movement ended up in a huge conflagration of violence in the taluks of Ernad and Valluvanad in which thousands of Mappilas died fighting the British forces in battles that raged for six months. The Hindu-Muslim unity that was the greatest slogan of the movement had been shattered in the wake of the Mappila rebellion and the two communities had drifted far apart from each other in the next decades.

So when Gandhi visited again, politics was not on his agenda. In 1924 and 1927, Gandhi’s visits to the region were focused on social reforms within the Hindu community. In 1924, he joined the agitators at Vaikom Mahadeva Temple, where the Congress volunteers courted arrest demanding equal rights to the untouchables on public roads around the temple. On his next visit in 1927, Gandhiji rejoiced over Travancore Maharajah’s declaration which opened the public roads to all his subjects.

On the fourth visit in 1934, Gandhiji focused on Harijan uplift and was seeking funds for his social reform efforts to bring some dignity to the lives of the most disadvantaged sections of Hindu society. It was during this visit that a girl called Kaumudi in Kannur came to meet him and offered all her ornaments for the cause. The young girl pledged in his presence that she would never wear gold ornaments again, prompting the Mahatma to write about the selfless deeds of the girl in his weekly journal, The Harijan.

“It was in those idealistic days of the national movement that I grew up,” said the veteran Gandhian as we chatted at his home in Kozhikode. In the years since his witnessing the Mahatma’s meeting that left an indelible impression on his young mind, Thayatt Balan himself has traveled far and grown into one of the tallest Gandhi followers in the state of Kerala. He has spent many decades as a Gandhian, working on the Mahatma’s greatest projects like spread of khadi and the message of ahimsa and eradication of untouchability. Even at this age, he is as loyal to Gandhiji as he used to be in his younger days, when he dedicated his life to spread the Mahatma’s messages.

“Some years ago, I had an eye surgery,” said the nonagenarian, “and I told the doctor who attended on me: Look, these eyes are precious because they have seen the Mahatma,” he chuckled.

In the Thayatt family, this devotion to Gandhi was like a contagion—his father and his two brothers were dedicated Gandhi followers too. Thayatt Sankaran, the older brother, was one of the most celebrated leaders of the Congress party in Malabar at one time, but later became a Communist fellow-traveller and editor of Deshabhimani weekly. Another brother, K Thayatt, was a well-known teacher and writer.

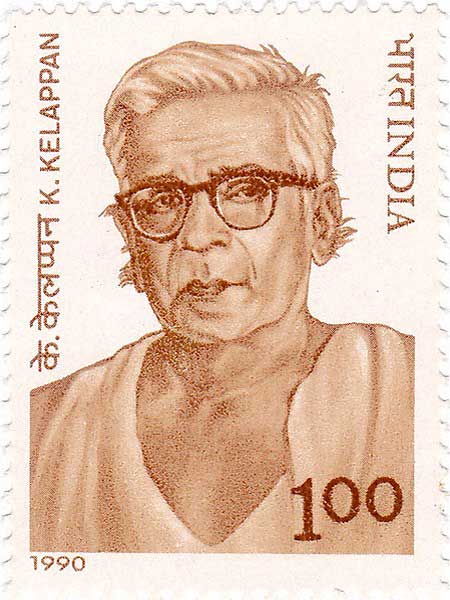

Thayatt Balan took to social work at an early age. He had planned to take up teaching to serve in the family-owned school but his life took a different turn. One day, ‘Kerala Gandhi’ K Kelappan came to visit their home. Kelappaji, as he was known among his followers, was a legendary figure as a freedom fighter, editor of Mathrubhumi and a social reforms activist in the Hindu community. He led the Guruvayur Satyagraha in the early thirties demanding temple entry rights for untouchable communities and among his followers in the historic struggle were young Congress activists like P Krishna Pillai and A K Gopalan, both of whom later became the tall leaders of the Communist party in Kerala.

In the initial days of independence, Kelappan had also served as the president of the Malabar District Board, an administrative system for districts in the erstwhile Madras Presidency which was ruled by C Rajagopalachari. He was also one of the founding leaders of the Nair Service Society (NSS). In the fifties, while Kelappan took to Sarvodaya movement and rural regeneration work, some of his followers became well known leaders in various political parties in independent India. Despite their political differences, most of them had maintained a great respect for Kelappan, a man of principles, simplicity and great integrity whose political career started in the early twenties of the 20th century. One of his historic interventions came during the days of Malabar Rebellion. As a young teacher at Ponnani, it’s said that he dissuaded an agitated mob of Mappilas who were marching to Tirurangadi to fight the British forces along with the Mappila rebels there.

During the time of the young Balan’s meeting with Kelappan, the great Gandhian was living at Gandhi Ashram at Malaparamba in Kozhikode, practically alone and advancing in age. “He asked me to join him in his social work and I was happy about it. Kelappaji persuaded my father to allow me to follow him,” recalled Thayatt Balan as he reminisced about his life. Soon both Kelappan and his young disciple were living at Gandhi Ashram in adjacent rooms, travelling all over, meeting people and trying to redress their grievances.

What distinguished Kelappan as a leader was his great sense of empathy for the most disadvantaged sections of the people whom he met in his daily life. On one occasion he was visiting a Harijan colony. There was an elderly woman who announced to the leader that her grand-daughter had attained puberty, an occasion of great festivities in those days. It was called thirandukalyanam, festively celebrated in Nair families, leading to the financial ruin of many families in the process.

“The elderly woman made her request that Kelappaji should take care of the celebration of her grand-daughter’s thirandukalyanam as they were poor,” and she reeled out a set of demands including a feast for all those in the colony and music with loudspeakers, a luxury in those days.

“I was surprised Kelappaji, instead of dissuading her, asked me to take a note of all her wishes,” said Thayatt Balan. He was not pleased with his leader because he thought it was wasteful expenditure. “I told him so in a sharp manner, when we had reached back at the ashram,” he said.

The next day, Kelappan explained the logic behind his actions. He said it was the people from upper castes who were celebrating such functions in the face of the poor people around them. Unless and until these social evils were erased by those who practiced it, “what moral right do we have to preach it to these poor people around us,” he asked. So he was accepting this elderly woman’s request as a matter of his own moral expiation. In fact, he did go to Thalassery to engage a loudspeaker service to bring music to the woman’s hut in the colony to the great happiness and pride of the residents there.

The next day, Kelappan explained the logic behind his actions. He said it was the people from upper castes who were celebrating such functions in the face of the poor people around them. Unless and until these social evils were erased by those who practiced it, “what moral right do we have to preach it to these poor people around us,” he asked. So he was accepting this elderly woman’s request as a matter of his own moral expiation. In fact, he did go to Thalassery to engage a loudspeaker service to bring music to the woman’s hut in the colony to the great happiness and pride of the residents there.

It was in those days that Kelappan got involved in some of the most controversial actions in his life, such as the Angadippuram Tali temple agitation in Malappuram and the campaign against the formation of Malappuram district by the EMS Government.

Kelappaji was already 78 years at the time and very feeble, living in the ashram when a few people came to complain about the prevention of Hindu devotees on their way to Sabarimala in the south and Kottiyur in the north making coconut offerings at the dilapidated and abandoned shrine on the highway, remembered Thayatt Balan.

“Kelappaji went there to inquire and I followed him,” said Thayatt Balan who remembered that during the days of Tali temple agitation, the elderly leader was subjected to immense personal insults and harassment. “The Muslim League was in power and their followers took out demonstrations regularly dubbing Kelappaji as the man who smeared sacred sandal paste on the stone that was pissed over by stray dogs…,” he said. That caused a communal flare up and the government intervened, taking over the place and declaring it as an archaeological site and built up some fortifications to prevent people entering it.

Kelappaji refused to relent and he began satyagraha against the government order. He was arrested, and he started a fast in the police station, which finally forced the government to backtrack and the site was opened to the devotees. It was this movement that gave rise to the temple renovation efforts that spread all over Malabar and the formation of Malabar Kshetra Samrakshana Samiti, he pointed out.

Kelappan’s final battle was against the EMS government as it took steps to form Malappuram district, carving out the new administrative unit bringing together the Muslim majority taluks in the Kozhikode and Palakkad districts. “Kelappaji was not against development of this region as the opponents accused, but he was concerned such a district with a focus on a specific community would prove to be harmful for our society,” said Thayatt Balan, who worked with Kelappan in those campaigns. He said many people were worried the old wounds of the division of the country on communal basis could revive as the slogans of the partition days like “Pakistan or Khabristan” that reverberated all over the region were still fresh in the minds of the people of Malabar.

It was in the height of this campaign that AKG, who was then briefly the State Secretary of the CPI (M), wrote an open letter to his former mentor Kelappan. Addressing him as “My dear Kelappettan”, the CPI (M) leader defended the government’s decision to carve out the new district on the grounds of acute backwardness of the region and the majority Muslims living there.

“Kelappaji initially was in no mood to get into a public debate with AKG, but then we pointed out that it was an open letter and it ought to be responded to in an open forum,” recalled Thayatt Balan. Finally a fitting reply was sent out to the press in which Kelappan addressed AKG as “My dear younger brother.” In the letter Kelappan defended his decision to oppose the district formation, asserting he would support every effort to develop the region, but would oppose any move to divide the people and the country for political expediency. The Malappuram district came into existence in June 1969, but four months later, in October, the government collapsed as the Muslim League, CPI and the Socialists left the CPI (M)-led United Front.

Kelappan died in 1971 and Thayatt Balan, like many of his followers, continued to work in the movements that he had left behind. Today, in his nineties, Thayatt Balan remains active. Recently, he was seen courting arrest along with veteran historian MGS Narayanan, in protest against the government’s refusal to provide adequate funds for a road widening project in Kozhikode city.

Most days, early mornings, he can be seen hurrying with his bag tucked under his arm, to catch a bus to a meeting or a dharna or a gathering for some social cause. On the occasions I have encountered him, I ask him why he is in such a hurry and he always gives the same response: ”Look, I have left behind a little work unfinished there,“ as he rushes off.