Muslim League Politics in Post-Independence Days: Part One

Late August, the police in Perambra, a town in Kerala’s Kozhikode district, registered a case against 30 Muslim youngsters, belonging to the Muslim Students Federation (MSF)—the students wing of the Indian Union Muslim League (IUML), for anti-national activities. They had allegedly waved a Pakistan national flag. Earlier in May, many BJP politicians from north India alleged the IUML supporters who came for the rally of Rahul Gandhi, Congress candidate in Wayanad, waved Pakistani flags. Both allegations received much hype from some national channels as well as in social media, though both were patently false.

But the campaign continues, with certain sections in Indian politics and media deliberately making efforts to put a question mark over the loyalty of Indian Muslims to the country and its unity and integrity. This is a dangerous game and could have very serious consequences in the long run. Hence it is necessary to look at the history of Indian Union Muslim League in the post-Independence India and its uncomfortable relationship to the erstwhile Muslim League that proposed the two-nation theory in the run-up to the division of the country in 1947.

This two-part essay makes an attempt to describe the evolution of Muslim politics in Kerala in the turbulent decades after independence.

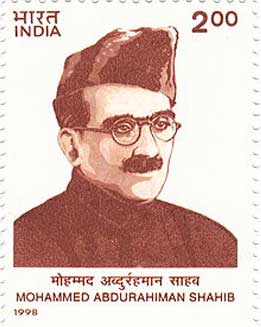

When freedom fighter Muhammad Abdurahman returned to Malabar in September 1945, after five years of incarceration in British jails during the Second World War, he found the entire region resounding with the slogan ‘Pakistan Zindabad’, in an expression of frenzied anti-Congress feelings that had gripped the Muslim community. The All India Muslim League, led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, had established a unit in Malabar at a conference in Thalassery in 1937, but its influence was only marginal among members of the community. But at the outbreak of the war, most Congress leaders were put in jail while Muslim League and Communist activists remained free to continue their political work. This situation had changed the political equations in Malabar.

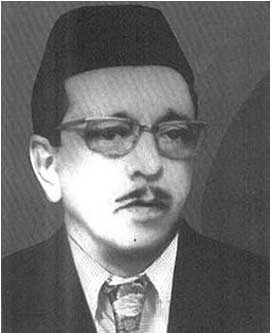

Abdurahman Sahib, as he was fondly addressed, was firmly opposed to the Muslim League and its espousal of the politics of communal nationalism. In the 77 days that he lived after his release from jail—he died on 23 November 1945—he addressed meetings in many parts of Malabar and outside, opposing the Muslim League demand for a separate country for the Indian Muslims. He faced severe threats to his person during those days and there were several attempts to manhandle him by League workers in various places. Abdurahman was, all along in his political life, a dissident Congressman who fought the dominant stream of Hindu upper-caste leadership in the Congress party. But he disagreed with the Muslim League and its leader Muhammad Ali Jinnah on a fundamental point: He thought the Muslims should try to redress their grievances within a free and secular India and not in a separate country built in the name of a community.

Abdurahman Sahib, as he was fondly addressed, was firmly opposed to the Muslim League and its espousal of the politics of communal nationalism. In the 77 days that he lived after his release from jail—he died on 23 November 1945—he addressed meetings in many parts of Malabar and outside, opposing the Muslim League demand for a separate country for the Indian Muslims. He faced severe threats to his person during those days and there were several attempts to manhandle him by League workers in various places. Abdurahman was, all along in his political life, a dissident Congressman who fought the dominant stream of Hindu upper-caste leadership in the Congress party. But he disagreed with the Muslim League and its leader Muhammad Ali Jinnah on a fundamental point: He thought the Muslims should try to redress their grievances within a free and secular India and not in a separate country built in the name of a community.

His arguments were simple and strong, and hence the violent reactions he faced. He stressed the cultural and linguistic divergences that kept the Malabar Mappila Muslims distinct from their north Indian brethren, who were demanding a separate homeland on the north-west and eastern parts of the vast Indian subcontinent. The Malayali Mappilas would never benefit out of it, and such a dangerous course would put them into serious difficulties at home, he reasoned. That argument, however, did not cut much ice with the community in the frenzied atmosphere of partition days. Interestingly, this separate nationhood theory then had the support of the Communist Party of India too, which justified it in the name of national self-determination, a theory promoted by V I Lenin in the days of Russian revolution.

As the Muslim League disbanded its National Council on the eve of the partition, it left behind the Indian Muslims rudderless after independence. It was in such a complex situation that some of those Muslim League leaders who stayed back decided to revive the party in independent India. It took place at a conference of the remaining members of the erstwhile All India Muslim League, convened at Rajaji Hall in the city of Madras, on March 10, 1948. The conference was organised by a group of leaders, mainly from Malabar, led by Muhammad Ismail, known as Quaid-e-Millath among his followers. He was elected president of the new political party and Mehboob Ali Baig of Bengal, the general secretary.

Among the delegates, there were differences of opinion as to the pros and cons of the move to revive the party. Many leaders argued against it, among them Abdul Sattar Sait, the most senior and influential leader of the League in the Madras Presidency, who later moved to Pakistan and became Ambassador to Egypt under Jinnah’s rule. However, the resolution was carried with nine votes against and 21 in favour. There were only 30 council members in attendance, as most of the members had left the country and many from the north and east decided not to attend at all. It had taken almost ten hours of heated debate on the resolution proposed by P K Moideen Kutty, a council member from Kuttippuram in Malabar, before it was put to vote. Among those who were in favour of forming a new party was Muhammad Ismail, K M Seethi Sahib and Advocate B Pokker—all leaders with their base in Malabar.

Most of the 30 representatives who attended the conference were from the Madras Presidency, where the partition riots had had little impact. The influence of the new party remained generally confined to this region, especially Malabar. It later spread to Travancore and Cochin regions in Kerala and also made some inroads into parts of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka among other places. During the days of Muhammad Ismail as president, it had as many as five members in the Lok Sabha and four in the Rajya Sabha, besides representation in various state legislatures like Assam, Bengal, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh and Delhi. However, except in Kerala, the League remained a peripheral player in Indian politics.

In the 1952 general election, the League was fighting alone in Kerala, pitted itself against the two fronts led by the Communist Party and the Congress. However, its base in Malabar was solid: League leader B Pokker won the Malappuram Lok Sabha seat and five members were elected to the Madras State Assembly. This state of political isolation changed, to a certain extent, during the 1957 Assembly elections. There were three political groupings in the fray, respectively led by the Congress, the Communist Party and an alliance between Praja Socialist Party (PSP) of Pattom Thanu Pillai and the League.

But the League’s political fortunes changed, once the great political uprising against the Communist rule under EMS Namboodiripad became intense. This violent agitation, known as Vimochana Samaram (Liberation Struggle), was in fact a combined assault on the elected government of the day by powerful caste and communal groups. The Nair Service Society led by Mannath Padmanabhan and the Catholic Church, who were aggrieved by legislations of the government on land reforms and education, launched the agitation by early 1958. It became aggressive once the Congress and PSP joined its ranks formally in June.

Initially, the Muslim League leadership in Kerala was not enthusiastic about the agitation, as they found some of the steps taken by the Communist government favourable to the community. First, the government was responsive to the pleas for removal of restrictions imposed by the British colonial administration on the construction of Muslim places of worship. The Muslim Ulema in south Malabar had taken a leadership role in resistance to the colonial administration and its exploitative policies from early 19th century.

In fact, the British had imposed such draconian measures like mass fines on entire villages, restrictions on people’s movements and use of weapons like knives, imposing rules like the Moplah War Knives Act, 1859. Such discriminatory practices by the state administration continued even after independence and it was the Communists who took notice of the Mappila grievances and initiated action to redress them. The government also had taken steps to provide special quota of 10 percent to Muslims within the 35 percent reservations for OBC communities. This was a demand raised by the Muslim League, in view of the poor representation for the community in government service because of its extreme backwardness in education.

But the League changed its equivocal policy toward the EMS government and decided to officially join the agitation at its state council meeting in Kozhikode on June 21, 1959. A month later, on July 31, 1959, the Government of India dismissed the EMS ministry through a Presidential order under Article 356 of the Constitution.

This turnaround in the Muslim League attitude to the liberation struggle has been a matter of debate in political circles ever since. In the initial days of the anti-government agitation, when the students and teachers were asked to boycott classes, mainly by the managements who ran these institutions, the League was not in favour of it. They thought educational institutions should be left undisturbed.

Secondly, they also felt that so long as the government had a majority support in the Assembly, it had a right to continue in power. This was the position taken by League president Abdurahman Bafaqui Thangal when veteran Congress leader K Kelappan launched an indefinite fast unto death demanding resignation of the government. At a meeting convened by Home Minister V R Krishna Iyer to find a solution to the fast at Thirunavaya, Thangal said such pressure tactics were not justified, as the government enjoyed majority support in the Assembly.

Still, the Muslim League later decided to join the agitation which generally served the interests of upper castes & communal elements based in the southern parts of Kerala. The irony of the situation was that even within the Congress party, some leaders from the erstwhile Malabar region had reservations about the way the agitation was being managed by south-based leaders like KPCC president R Sankar.

There are several explanations for the League approach, though the party has never cared to explain it. First, it found a chance to break its political isolation (on account of its communal branding) by joining hands with powerful Christian and Nair interests; secondly, as the Communists were dubbed anti-religious, the conservative Muslim folk generally were not comfortable with Communist rule; and thirdly, the party expected a quid pro quo and accommodation in the future governments.

But there seems to be another aspect to this: The League decision to join hands with the Nair and Syrian Christian elites, who normally looked down upon the Muslims, was a signal of the powerful hold of the entrenched elite groups within the Muslim League itself. It is a fact that the League had at least three major social groups aligned within its ranks and leadership: the landed gentry from Kannur, Kozhikode and Kodungallur; the traders and business bourgeois from Calicut, and the workers and poor peasants from Malappuram, besides the different groups of Ulema who were all at loggerheads with each other, with the League working as an umbrella organization bringing them together.

The liberation struggle was an expression of the fears of the social elite against the rising power of the subaltern, who refused to bow down to the old social customs and practices any longer. American academic T J Nossiter writes: “What excited and alarmed the higher castes was not…any imminent fear of robbery or assault, but lawlessness of the mind.” He quotes a wealthy Christian: “you saw that fellow…he is an unseeable. …Until six months ago that fellow knew his place; when he saw me he would get off the path, today he nearly brushed me aside. That is what they call equality.” (Communism in Kerala: A study in political adaptation, University of California Press, 1982; p.159.) And many members of the Muslim elite also shared the same sentiments.

After a brief spell of President’s rule, the state went on to another Assembly election in January 1960. This time the Communists were defeated by the combined forces of Congress, PSP and Muslim League. The League had won 11 seats in the 126-member Assembly, but when the talks about the formation of a new government were on, Congress took the line that League could not be accommodated in the ministry. They were a communal party and Jawaharlal Nehru, the prime minister who had described the League as a dead horse, was not inclined to support its revival.

The PSP and sections in the state Congress leadership were supportive of the League claims, but the Congress national leadership refused to budge. So a compromise formula was ironed out and the League was offered the speaker’s post, which they finally accepted. K M Seethi was chosen the speaker. Pattom Thanu Pillai became the chief minister and two years later, upon his resignation, Congress leader R Sankar took over the reins.

Owing to internal differences and a major split in the Congress in 1964 birthing the ‘Kerala Congress’, this government also fell and after another spell of President’s rule, the state again went into a general election in 1965. By this time, the Communist Party too had been split, and the two factions of CPI and CPI (Marxist) were at loggerheads. As in the past, there were several political formations contesting for power.

Despite the split, Communist leaders made an attempt to put forward a United Front of Left parties. But this attempt failed owing to differences over relations with Muslim League and the newly formed Kerala Congress, both parties dubbed communal. The CPI was opposed to having any understanding with Muslim League while the CPI (M) was in favour of some adjustments with it, as the Communist Party had done in the 1957 and 1960 elections.

T J Nossiter, in his book Communism in Kerala, comments: “It seems reasonable to accept Namboodiripad’s reading of the situation–that the CPI intentionally pressed the League issue so as to provide itself with a principled exit on the presumption that a beleaguered CPI (M) would now accept the CPI’s claim to an allotment of seats.” (ibid., p.188). Finally, the CPI decided to contest in the company of the Revolutionary Socialist Party (RSP); the CPI (M) struck up an alliance with Samyukta Socialist Party (SSP) and Karshaka Thozhilali Party (KTP) and also had seat adjustment with the Muslim League in six constituencies. Bereft of allies, the League was able to win only six of the 16 seats it contested.

This election also failed to bring in a stable government. As negotiations to form a government failed, the state had to endure a third spell of President’s rule. So, when the 1967 Assembly election was announced, both Communist parties were agreeable to join hands with political outcasts like Muslim League. The CPI (M) leader EMS Namboodiripad gave a theoretical justification for the formal alliance he proposed with the League. He argued that majority communalism was more dangerous than minority communalism and hence such tactical adjustments were a need of the hour in order to defeat the main enemy—the Congress party.

The CPI did not argue with this formulation, as they had learnt a lesson in the past election– they had lost substantially while the CPM made gains with low-key understandings with the League. So this time, negotiations were easier and both Communist parties agreed to have a formal alliance with Muslim League. The League, on its part, came out with a resolution at its Working Committee that it was ready to cooperate with all non-Congress parties, including Communists, on the basis of a Common Minimum Program.

In the seat sharing exercise, the League was allotted 15 seats, and the CPI (M) took 61, CPI 24 and SSP 23, leaving the rest to minor parties in the United Front. Namboodiripad’s United Front won a resounding victory, winning 113 seats out of 127. The main rival, Congress, could win only nine seats, its worst electoral debacle in the Kerala, with the Kerala Congress winning the remaining five seats in a three-cornered contest. The Muslim League won 14 seats, losing only one of the seats it contested.

Nossiter says it was a win-win for the League: “The League’s position as always in Kerala was dictated by practical politics: Congress would not deal with it on the grounds that it was a communal party; younger Muslims in Malabar were proving responsive to Communist influence; and the uninhibitedly bazaar approach to politics of the League’s leadership in Kerala—business with anyone if the price was right.” (ibid, page 204).

For the League the gains were substantial: they were offered two portfolios in the ministry, its maiden turn in the state cabinet, and an implicit understanding that the United Front ministry would attend to the under-representation of Muslims in government service. The significance of the last point could be gauged from the fact that in 1967, only 22 of the 511 government jobs carrying a salary of Rs. 80 or more per month were held by Muslims. There was no fixed quota for Muslims in the system of reservation for the backward classes in government service at the time.

But this government, again led by EMS Namboodiripad, ran into rough weather and collapsed in two years. The difficulties arose when the United Front constituents including the Socialists, CPI and the Muslim League felt suffocated by the dominance of the CPI (M) in governance, something which they described as “big brotherly attitude”.

By the end of 1967, there were reports of the formation of a mini-front of smaller parties within the government, constituting the CPI, SSP and Muslim League. Their grievances were as follows: The CPI (M) insisted on redrafting of agreed policies during implementation; the party interfered in the administration of departments allocated to other parties, and publicised these differences with a view to browbeat the allies and gain advantage in the field. The CPI (M) also was accused of engineering internal conflicts among their allies, and the SSP faced a series of splits and some of their ministers and MLAs defied the party leadership. These inner-party and intra-party differences came to a head with a series of corruption charges against many ministers.

Finally, on 24 October 1969, a resolution of no-confidence in the government was carried by 69 votes against 60 in the Assembly; CPI, League and what remained of the SSP joining hands with the Congress and the Kerala Congress in the opposition to bring down the government. Thus ended the second ministry led by EMS Namboodiripad, this time with practically little to claim by way of progressive legislations in its 32-month existence. It could, however, take credit for carrying the Agricultural Relations Bill through all its stages in the legislative process, though its passage was left to the next government. For the League, which had two ministers—C H Muhammad Koya and Avukkader Kutty Naha—its main gains were the formation of Malappuram district, and the setting up of Calicut University, the first in the Malabar region which helped promote higher education in this backward region.

The downfall of the second EMS ministry proved to be a turning point in Kerala’s electoral politics: For the first time, it paved the way for a new, stable political alliance with C Achutha Menon of the CPI leading it. It was in many ways an accident of history: The mini-front that had brought down the United Front government had no majority support to form a government on its own. Namboodiripad, quite reasonably, expected a period of President’s rule as in the past before a new election. But Governor V Viswanathan used his discretion and invited CPI leader Achutha Menon to form a new government in the state.

Achutha Menon was sworn in on 1 November 1969, and he led a minority government with eight ministers—representing the CPI, Muslim League, Socialist Party and Kerala Congress. The RSP was also part of the front, but did not join the government. The Congress (R), the dominant faction in Kerala supporting Indira Gandhi after a split at the national level, pledged support to the new government but opted to keep out of the ministry.

It was no smooth sailing for Chief Minister Achutha Menon or his Home Minister, C H Muhammad Koya. The CPI (M) had openly threatened violent agitations and there were, according to official figures, as many as seven police firings between 1 November 1969 and 31 August 1970, killing nine persons. The CPI (M), however, claimed there were 42 deaths in police firings and other actions during mass agitations against the government. Namboodiripad, in a public speech, warned C H Muhammad Koya that he would face the fate of Sir C P Ramaswamy Iyer, Travancore dewan who was attacked with a sword, and a few days later, the League leader was attacked with an acid bulb by a CPI (M) sympathiser at Thalassery.

After laying the groundwork for a stable political coalition, Achutha Menon announced the disbanding of the legislature and advised the Governor to go for a mid-term election to the State Assembly in 1970. The CPI (M) protested because Achutha Menon would continue as care-taker chief minister, but what the outgoing chief minister had done was perfectly legal and constitutional.

Looking back, it is evident that 1969 was a watershed in Kerala politics: It helped the rivals to turn the tables on CPI (M), skillfully adapting the same principles of united front tactics that Namboodiripad had perfected to his advantage. Until then, the mainstream nationalist parties like Congress were not willing to work with the Muslim League, and the result was continued political instability. Achutha Menon put an end to this politics of untouchability and persuaded the Congress under K Karunakaran to join his government after the 1971 general elections, in the second Achutha Menon government took oath in September 1970.

The younger elements in the Congress led by A K Antony had reservations about such a policy of accommodation, but Indira Gandhi’s view that in Kerala the Muslim League was not a communal force ensured that they too fell in line. This government not only completed its full term of five years—for the first time in the state’s history—but continued in power till March 1977 thanks to the declaration of internal Emergency by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in June 1975.

The Achutha Menon government also faced its crisis moments, but its achievements were long-standing. First, it put an end to the era of political instability and truncated governments, as all the previous ministries were either short-lived or stillborn. The fifties and sixties were interspersed with regular spells of President’s rule, a system of governance by bureaucrats with no accountability and no long term plans for the welfare of people.

Secondly, the Achutha Menon ministry proved to be a model for united front governance, as he could hold together most of the disparate front partners without serious friction or infighting. Thirdly, it laid the foundation for a welfare-oriented and responsive public administration through its various administrative and legislative actions and the establishment of a number of pioneering institutions that proved to be critical to Kerala’s future development. The result was that in the 1977 election, the coalition was re-elected to power, for the first and only time in Kerala’s history. K Karunakaran took over as the Chief Minister, as Achutha Menon had retired from active politics at the end of his term.

In the Muslim League, differences among leaders began to crop up soon after party national president Abdurahman Bafaqui Thangal passed away in Mecca in 1973. Bafaqui Thangal was a charismatic politician and a powerful religious leader and the force of his personality held the various factions in the party together. The split became public with the withdrawal of support to the Achutha Menon government by a dissident group of six MLAs in the 11-member Muslim League legislature party, in March 1975. This group later joined forces with CPI (M)-led opposition in the Assembly. Soon, they formed a rival party known as All India Muslim League (AIML) at a meeting in Thalassery, with M K Hajee as president.

The split was an expression of deep fissures in the monolithic power structure of the Muslim League. It was known for firm inner-party discipline and loyalty to the leadership and the long history of religious leadership in the community’s political affairs had helped cement this phenomenon. But by the mid-70s, rival power centres came to existence and the dissidents were led by people like CKP Cheriya Mammu Keyi, of the aristocratic Keyi family in Thalassery, and Syed Ummer Bafaqui Thangal, nephew of the late Abdurahman Bafaqui Thangal, of Koyilandy. The official League was led by PSMO Pookoya Thangal of Panakkad, and Kozhikode-based leaders like C H Mohammed Koya and B V Abdulla Koya.

Immediately after the lifting of the Emergency, efforts were on to bring unity back into the party. The experiences of the Emergency itself turned out to be a signal how disunity and consequent sidelining from power could prove costly for the elite sections in the community. Many All India Muslim League leaders were put in jail during the Emergency and some of the Muslim businessmen, who were patrons of the League, were hit hard by the central government’s drive against smuggling and tax evasion. In the first year of the emergency, the Home Minister reported that economic offences involving a total of Rs. 67 crore had been detected, and many arrested, among them prominent businessmen K S Abdulla of Kasargod, and Kallatra Abdul Khader Hajee of Kozhikode, both League veterans. The former was to play a key role in the reunification talks of the Muslim League, later in the early 1980s.

(To be continued)

Cover Image: Indian Union Muslim League’s flag

Read Part 2: The History of Indian Union Muslim League