Devavrat, better known as Bhishma Pitama, was virtue personified. And yet, his silence when Yajnaseni, known to us as Draupadi, was disrobed in the Kaurava court, deprived the grand old man of due honour. Bhishma Pitama’s association with Duryodana and his brothers led him to commit acts that were not virtuous in the end. K A Neelakandan’s rendition of the Mahabharata from Draupadi’s eyes—Yajnaseni—leads the reader to hold Bhishma differently and shorn of glean.

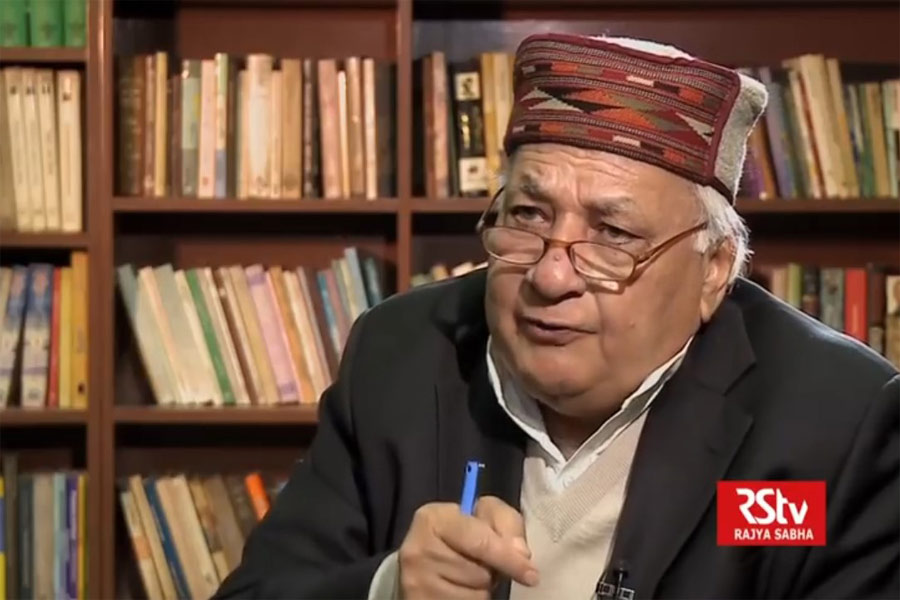

This short invocation of the Mahabharata, an epic that holds sway over a people across communities and generations in our society, will help comprehend and locate Arif Mohammad Khan, the Governor-elect of Kerala.

Let me, at the outset, clarify that I am not glossing over some issues of impropriety in making someone a Governor despite his association with active politics in the recent past—a factor that the Justice Sarkaria Commission held as undesirable for healthy conventions in its report in the 1980s. This recommendation, indeed, was followed in its breach more than adhered to in all the years since then and the Raj Bhawans remained, most often, reduced to appointing political persons either to ensure them the comforts of life or to play political games.

Arif Mohammad Khan, hence, will not be the first one who will end up in such a list and certainly not the last given the way political parties across the spectrum have shown their penchant to reduce the Constitution and its democratic scheme into a plaything.

I came across Arif Mohammad Khan first as a student in University and more specifically when we had cause for celebration in April 1985. The cause was the Supreme Court verdict in the long drawn battle for justice by Shah Bano seeking the right to maintenance on being divorced by her husband. A Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court consisting Justices Y V Chandrachud, O Cinnappa Reddy, Venkatramaiah, Ranganath Mishra and K T Desai decided that Shah Bano was entitled for maintenance (the sum being paltry though) in a case where she was represented by Daniel Latiffi, as lawyer.

It was a milestone in the struggle for justice and women’s rights and the then Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi, fielded Arif Mohammad Khan, a minister in the Union Cabinet to explain why the Government stood by the apex court’s verdict and against the demand by a section of MPs representing the interests of Muslim orthodoxy. Khan spoke eloquently and for those of us who had also welcomed the court’s decision, Khan did appeal to reason and progress.

Meanwhile, the government indulged in some machinations involving the Judicial Magistrate’s Court in Faizabad to throw open the Babri Masjid for worship in February 1986, until then under lock and key based on a judicial order dating back over three decades. And in what historians will call a chain of reactions, Rajiv Gandhi decided an about-turn on the Shah Bano verdict. A Bill was introduced by the Government (which was in most parts a cut-copy-paste job of a Private Member’s Bill moved earlier by Muslim League MP G M Banatwala) to render the apex court decision null and deny the Muslim Women the right to seek maintenance from her ex-husband.

Khan had spoken against Banatwala’s Bill when Rajiv Gandhi fielded him to take on the orthodoxy at an earlier stage. When Khan found his own government now moving the opposite way and turning the clock back, he quit the cabinet and also left the Congress party.

For us, in the university, he was a hero and we did call him over for a public talk. It was an established tradition in our university then to have anyone who had a view to come and speak. I also remember Syed Shahabuddin, a former Foreign Service officer then with the Janata Party, addressing such gatherings against the apex court judgment. Khan had become a knight in shining armour for many of us. I still hold his views on the rights of Muslim women salutary.

His stint with V P Singh, who too was eased out of the Congress about the same time but for different reasons, was tumultuous. Khan was consciously kept out of the campaign in the Allahabad by-elections by V P Singh for it was felt that he had antagonised the Muslim community with his views in favour of Shah Bano’s right to maintenance. And yet, when V P Singh constituted his cabinet in 1989, Arif Mohammad Khan found a place—only to fall out caught in the cross-fire between Singh and Chandrashekar.

Khan stayed in oblivion for almost a decade since then but never stopped engaging with friends and others on affairs that were political, religious and social. He was, after all, a politician—unlike scholars who held similar views.

In other words, Arif Mohammad Khan was not like Prof. Irfan Habib, who had spoken out against Islamic Fundamentalism all his life and faced attacks, physical on many occasions, for his views. Nor was he like Asgar Ali Engineer, a scholar in Islamic texts, someone who spent his lifetime campaigning against the scourge of fundamentalism and speaking up for liberation of the Borah Muslims and the women in that fold. Or for that matter Prof. Zoya Hassan, noted academic and women rights activist who told Rajiv Gandhi in 1986 that he was taking the nation backwards contrary to his claims of taking India into the twenty-first century.

Khan was a politician and this took him first to the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) in the late-nineties and later, to the Bhartiya Janata Party, in 2004. Once in the BJP, he sought to blind himself of the rationale by which he had spoken in favour of the Supreme Court’s decision in the Shah Bano case and quit the Rajiv Gandhi cabinet.

He was, in the mid-nineties, also charged of receiving funds through the hawala channel, in the infamous Jain Hawala case, only to be let off, like everyone else (which involved a cross section of leaders across the political spectrum). All those cases fell flat only because the nexus was not proved as required under the law.

To put things in perspective, Arif Mohammad Khan will be remembered by posterity as are Bhishma or Drona are held in the epic. They ended up in the wrong camp, whether it was to enjoy the comforts of the palace and the paraphernalia or for any other reason, and kept quiet when Yajnaseni was molested in the Kaurava courts.