It is important to understand the background of Congress party’s overtures to the progressive and socialist elements in Indian politics. Nehru’s idea of relaunching ‘Congress with socialist characteristics’ did not materialize out of thin air; rather, it was shaped through some fortuitous circumstances and perspectives of certain individuals. The idealism nurtured during the independence movement had brought new vision, vigour, verve and valour to the country in the immediate aftermath of independence. This idea of rejuvenation within politics and society gradually began to fade.

The loss to China in 1962 impacted domestic politics. Nehru was a shattered man. The other Congress leaders realized that they needed to revitalize the party by transforming themselves and the party programmes. Congress seemed like a defunct saviour and Nehru’s aura diminished post the Sino-Indian War. The party was in desperate need of some new vigour and new energy. In this scenario, the Congress party revived its goal of working towards a socialistic society that was adopted in the Avadi session in 1955 and extended an invitation to all those who believed in the socialist ideology to join hands with the Congress.

In the aftermath of the 1962 military debacle at the hands of China, May of 1963 witnessed three of the fiercest critics of Nehru getting elected to the Lok Sabha in the by-polls—Minoo Masani from Rajkot, Acharya Kriplani from Amroha and Dr Ram Manohar Lohia from Farrukhabad. In this backdrop, it was a good strategy for the Congress to attract progressive forces from other political outfits. The coming together of some of the PSP leaders and the Congress party should be studied in this context.

In 1963, the PSP faced a new ideological crisis. At the Betul party conference, Ashok Mehta proposed his new theory, ‘Compulsions of the Backward Economy’, which suggested that to achieve rapid national rejuvenation in developing countries, the opposition parties should cooperate with the government on certain critical issues. In essence, Mehta’s proposal was advocating that the PSP cooperate with the Congress government.

Subsequently, Jawaharlal Nehru invited Ashok Mehta to assume the deputy chairmanship of the Planning Commission. Eventually, Ashok Mehta accepted the position and led an Indian delegation to the United Nations. However, before his departure, Mehta made an earnest appeal to his fellow partymen to let him keep his membership of the party. However, Ashok Mehta’s appointment to the Planning Commission led to major conflicts within the PSP as most of the senior leaders were vehemently opposed to Mehta’s proposition.

Even though Chandra Shekhar did not agree with Mehta’s proposal, he was appalled at the callous manner in which Mehta’s party membership was suspended. Chandra Shekhar was of the opinion that Ashok Mehta’s proposal of collaboration with the government was not wholly new. In the 1950s, the Socialist Party had proposed the formation of an all-party consensus on India’s foreign policy. It was quite possible that Jawaharlal Nehru did not agree to this proposal due to his constraints. In the changed scenario, if Nehru had accepted the earlier suggestion of the Socialist Party and Mehta was following up on that very proposal, he should have been allowed to retain his party membership.

During the discussion on the issue of Ashok Mehta’s membership in the party’s national executive, Chandra Shekhar spoke in favour of Ashok Mehta and argued that no decision should be taken on this issue in Mehta’s absence when he was leading an Indian delegation to the United Nations. However, despite his objections, the National Executive Meeting decided to terminate Ashok Mehta’s membership.

Chandra Shekhar responded, ‘You terminate the membership of Ashok Mehta, and I shall terminate my membership from the national executive. On his return from the United Nations, Ashok Mehta met Chandra Shekhar and the following conversation was reported:

Ashok Mehta: Do you believe in my thesis?

Chandra Shekhar: No, I do not.

Ashok Mehta: You are a young man, you should go along with the party; why are you resigning? Do not resign from the national executive.

Chandra Shekhar: I have taken my decision and I do not need your advice.

The last statement exhibits a remarkable trait in Chandra Shekhar—once he made up his mind, he would not budge from his decision. This steadfastness never left him—even as the president of Janata Party, as the prime minister of India, and as the only parliamentarian of his party. Chandra Shekhar’s departure from the national executive led a number of party leaders from Uttar Pradesh to withdraw from the party’s organizational work.

In January 1964, Chandra Shekhar resigned from all the party posts. A few days later, Ashok Mehta called for a meeting of party leaders at his residence in Delhi. He informed the leaders about Jawaharlal Nehru’s wish to gain the support of the socialists. Mehta believed that the struggle for socialist policies could be pursued more vigorously by joining the Congress. While the meeting was in progress at Mehta’s residence, Nehru’s invitation to meet these PSP leaders was also delivered.

The next day, eleven of these leaders went to meet Jawaharlal Nehru at Trimurti Bhavan. Chandra Shekhar was not in this delegation. His friend O.P. Shrivastava remembered that Indira Gandhi extended a warm welcome to them and was introduced to each one of these leaders. She said that it was her father’s wish that the socialist leaders join the Congress party. Jawaharlal Nehru was not well and, in a faint voice, he thanked the leaders for visiting him. Nehru accepted Genda Singh’s invitation to participate in a proposed convention of the socialist leaders. A meeting of the PSP leaders willing to join the Congress party was held in Lucknow in the second week of May 1964. Ashok Mehta announced 10–11 June 1964 as the dates for the All India Socialist Convention after discussing it with Nehru and the Congress’s working President Kamaraj. While all this was happening, Chandra Shekhar had set out for a tour of Purvanchal as he did not intend to be present at the proposed socialist gathering.

Nehru’s Death and its Aftermath

Jawaharlal Nehru passed away on 27 May 1964, leaving the entire nation in a state of shock and grief. Kamaraj, however, insisted on proceeding with the socialist convention as per schedule. The socialist convention went ahead as planned in Barahdari, Lucknow, and was attended by the acting Prime Minister Gulzarilal Nanda and the Congress President Kamaraj, who was playing the role of kingmaker in the Congress party in the aftermath of Nehru’s death.

Chandra Shekhar did not attend this convention. PSP office-bearers passed a resolution to suspend his membership from the party, for his open support to Ashok Mehta. Chandra Shekhar did not leave the party on his own accord but was expelled from the party. Now, he was caught in a bind—his own party had banished him, the other socialist parties were in complete disarray, and he could not bring himself to work with Dr Lohia and Raj Narain. Eventually, after spending six months in Rajya Sabha as an independent member, and after a lot of introspection, he decided to join the Congress.

Lal Bahadur Shastri had assumed the prime ministership by then and Chandra Shekhar believed that a major political force like the Congress could be steered towards socialism. It was this belief alone that made him join the Congress. He was one of the last among the PSP leaders who joined the party and was not keen on getting any position after formally joining the party. Instead, he was more interested in influencing the policy orientation of the party.

Chandra Shekhar recalled his first meeting with Indira Gandhi at a party programme in Mahuva, Gujarat, after he had joined the Congress. Both of them had travelled in the same train but met only at the podium during the function. As he was introduced to Indira Gandhi, she mentioned that she had heard a lot about him. Later, in New Delhi, Chandra Shekhar did not feel the urge to meet Indira Gandhi although a number of his friends repeatedly requested him to visit her. People like Gurupad Swamy, I.K. Gujral and Ashok Mehta used to meet Indira Gandhi every evening. They insisted that he should also join these informal get-togethers. Ultimately, Chandra Shekhar went to see Indira Gandhi.

Below is the casual conversation between the two at this meeting and it reveals a lot about Chandra Shekhar’s frank and forthright approach to politics.

Indira Gandhi: Do you consider Congress party a socialist unit?

Chandra Shekhar: No, I do not believe that Congress is a socialist organisation, though some people believe so.

Indira Gandhi: Then, why did you join the Congress?

Chandra Shekhar: Do you wish to know the truth?

Indira Gandhi: Indeed, I do

Chandra Shekhar: I dedicated thirteen years of my life to the PSP and worked with all my capabilities and honesty. I tried my best to steer the party towards the socialist path. However, after working for a long time with the party, I realised that its organisation was in disarray and the party itself was disoriented. It dawned on me that nothing substantial can be achieved in this scenario and, considering Congress to be a major political force, I decided to join the party and work for those objectives.

Indira Gandhi: What would you like to do now that you are here?

Chandra Shekhar: I would like to steer the party towards true socialism.

Indira Gandhi: And if you don’t succeed?

Chandra Shekhar: I will endeavour to break the party, for I believe that unless Congress is fragmented, no new kind of politics can emerge in the country. My first effort would be to bring socialism to the party but if I fail, there will be no option left other than to ensure its disintegration.

Indira Gandhi: I am simply asking you certain questions and this is how you respond to me?

Chandra Shekhar: If you are asking me questions, my answers will be directed to you.

Indira Gandhi: What do you mean by breaking the party? What can be achieved by this?

Chandra Shekhar: Congress has morphed into a big banyan tree and no other plant can grow under its shadows, therefore, unless this party is fragmented, no revolutionary change can be forthcoming.

Chandra Shekhar later recalled that at the end of the conversation, Indira Gandhi was looking at him in utter astonishment. This was the very first informal chat between Indira Gandhi, the elite among the elites, and Chnadra Shekhar, the subaltern among subalterns.

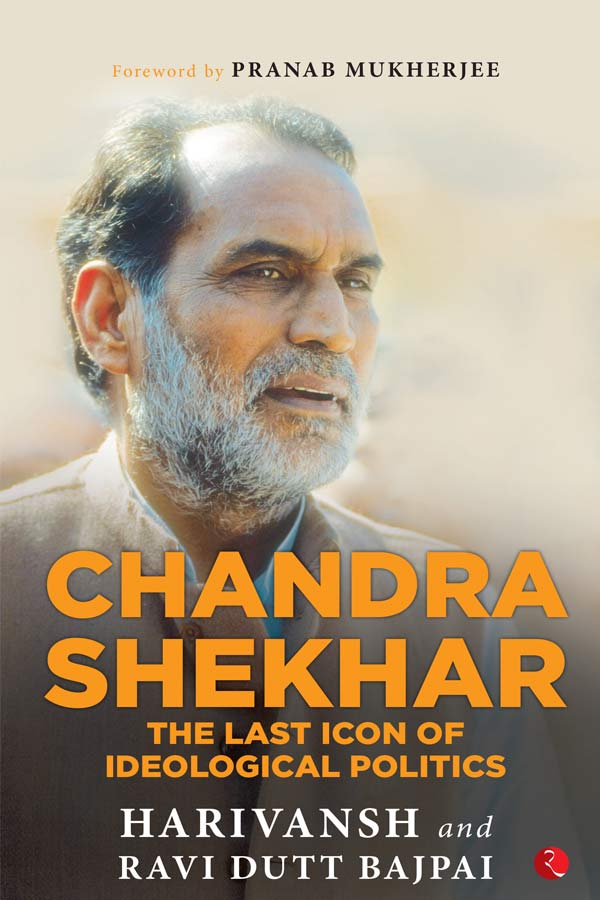

Excerpted with permission from Chandra Shekhar: The Last Icon Of Ideological Politics by Harivansh and Ravi Dutt Bajpai, published by Rupa, July 2019