With a harsh summer nearly behind us, the south-west monsoon is round the corner. The south-west monsoon of 2018, which had the state go through unparalleled calamity, is fresh in our memory.

The flood which submerged half of Kerala’s villages had affected one-sixth of its population. By late August, it had claimed 500 people, with many missing and unaccounted for. On the economic front, Kerala suffered an estimated loss of US$ 2.8 billion by way of damage to 100,000 buildings, thousands of acres of agricultural land and crops, about 10,000 kms of roads and highways and 280 bridges.

Kochi and her suburbs had their share of woes too. Places like Edapally and Cheranalloor were inundated. Aluva, Kalamasseri and Eloor were cut off when River Periyar overflowed its banks, with the authorities opening the shutters of many upstream dams.

The monsoon of 2018 turned a killer through various factors viz:

Flooding of the state’s major rivers and interconnecting backwaters flowing in spate, overflowing their banks and much beyond, when shutters of 35 of the state’s 54 dams were opened for the first time in history.

Landslides caused by unscientific and illegal construction of concrete structures, which the Gadgil and Kasturirangan reports had warned about.

Choking of major canals and drains, especially the non-biodegradable plastic, causing water to overflow by preventing its egress into the sea.

Kochi suffered from the floods due to the third factor. Perandoor canal, the major ‘vein’ that drains water from the city existing below sea level into the sea was choked with plastic waste so much so dirty water inundated areas like Edapally and Cheranalloor, dirtying and infecting homes. Choked drains across the city added to the misery.

The weather man has predicted a normal monsoon this year too. A city like Kochi has to be ‘monsoon-ready’. The authorities must, on a war footing, go on a massive drive to clean clogged canals, especially the Perandoor Canal, and the network of veins that exist beside roads and run through the concrete jungle—the numerous drains that ultimately drain water into the sea.

Local self-governing bodies must take up the responsibility to clean the city of tonnes of waste rotting on roads.

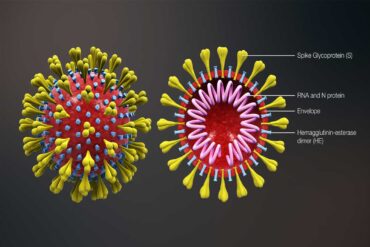

Plastic, forming the major component of such waste, collect rain water, in which mosquitoes, especially of Aedes Aegypti species, which spread deadly diseases like dengue and chikungunya thrive.

Waste, which invariably contains food disposed from homes, is a source of food for rats and stray dogs. Rats spread the deadly leptospirosis (rat fever), and dogs attack humans, a phenomenon being noted increasingly among dogs, of late.

The Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB) had virtually rendered the city’s roads unmotorable, and also unfit for pedestrian use by digging them to lay the underground 220 KV cable. These roads must be repaired well before the onset of the monsoon or they will soon look like tilled paddy fields.

Commuting the Cochin bypass is a nightmare due to gargantuan traffic blocks at bottlenecks like Palarivattom (where the over bridge is under repair, Vytilla and Kundannoor (where over bridges are being constructed—for years now).

The woes at these traffic bottle necks can be considerably reduced if the service roads to these busy junctions are repaired. This must be done well before the monsoon sets in, failing which the rain water could render these junctions worse than ploughed agricultural land for traffic to ply on.

Squalls being a regular feature of the monsoon, the KSEB and the Kochi Corporation must undertake the job of cutting large branches of senescent trees, so that death and destruction caused by tree falls and power outages due can be minimized.

As the old adage goes, prevention is always better than cure.