Calm is still our language.

Will we ever find our language,

an ‘other’ language?

—Kamal Kumar Tanti

When the country is on the brink of war or when we limp back to normalcy after high octane nationalistic and war-mongering rhetoric, it’s time to look at an emerging voice from Northeast India, who is up for reckoning in the Indian English landscape through translations (quite an effective praxis for national integration). In general, literature in translation into English may not make much news as compared to poetry conceived and written in the imperial tongue.

Kamal Kumar Tanti, who hails from the Adivasi Tea-Garden Labourer Community in Assam, is a poet without any qualifiers. He does weave a nascent perspective on our notion of History (capital H); engage with language both as a medium and as a site of resistance, considering that the tea garden labourer community has its own distinct dialect fertile with specific traits of their culture catalysing their self-perpetuation.

Taking a cue from Adonis (widely considered to be the leading voice in Arabic poetry), alienation could trigger creative self-expressions. If so, Tanti’s soul could be twice alienated; firstly, from the national imagination of our country (shared by the rest of Northeast) and secondly by the mainstream Assamese cultural hegemony, who have named his community after a commodity (borrowing his own words).

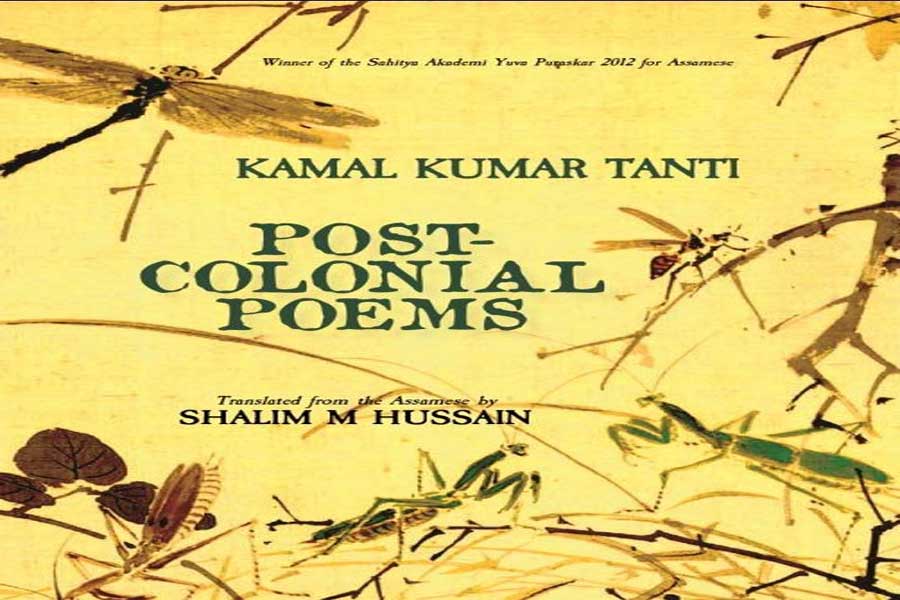

The Sahitya Akademi honoured him with the Yuva Puraskar in 2012, but it may not have initiated measures to make his writing available in English or other vernaculars, though there are many northeast literary festivals—voices from the northeast find scant attention in the national imagination of India. These acts of epistemic violence, resulting in intentional overlooking of literature and knowledge produced by the margins in the national discourse of India, makes Tanti even more relevant today.

Tanti hails from a landscape where writing is inextricably intertwined with activism and socio-political intervention. Interestingly, his collection of poems in English translation is titled Post-Colonial Poems published by Red River, an independent press run by poet and translator Dibyajyoti Sarma.

Thus, from the conception of a poem and composition of a collection to the choice of the translators and the publishing house become fraught with myriad and mutually oppositional issues. It is in this difficult terrain that we should foreground this impressive collection of poems rendered into the English idiom by Dibyajyoti Sarma and Shalim M Hussain, who themselves are distinct voices in Indian English poetry.

The highlight of this collection, in my opinion, is that Tanti retains freshness of imagery drenched in insight, and thereby never slips into a mere cultural document without much artistic nuance. He steers clear of self-exoticism, which sells well in the present neo-liberal marketing ethos. Last, but not the least, Tanti is a talent who has emerged.

What I like specifically about his poems when I read him in translation?

His verses have a self-awareness that is quite rare compared to the current trends in Indian English Poetry, in addition to an unrelenting quest for identity, an intimate relationship with language and the audacity to tread a unique path in the labyrinth of our History (capital H) distinguishes a major poet from a minor one, Tanti is your poet.

There are telling lines which I believe applies to his identity as a poet and also his generic identity as writer engaging with North East., like for example, “Now people say, this is heritage, a vestige of society.”

I quote and celebrate some of his lines which speak to my soul and my own engagement with language.

“We are trapped

in their coils

in the damned illusion of language.”

Tanti is one of the poets who is engaged in a mission of reclaiming one’s own history (entangled within one’s language), major poets of the past century like Aime Cesaire and Kamau Brathwaite had attempted this, and in the act, joins the camaraderie of some luminaries. Shalim Hussian and Dibyajyoti Sarma have successfully chiselled verses in Indian English idiom without any flabby parts. I often return to this book of poems.