“Every significant case has an unwritten legend and indelible lesson. This appeal is no exception, whatever its formal result. The message, as we will see at the end of the decision, relates to the pervasive philosophy of democratic elections which Sir Winston Churchill vivified in matchless words:

At the bottom of all tributes paid to democracy is the little man, walking into a little booth, with a little pencil, making a little cross on a little bit of paper-no amount of rhetoric or voluminous discussion can possibly diminish the overwhelming importance of the point.

If we may add, the little, large Indian shall not be hijacked from the course of free and fair elections by mob muscle methods, or subtle perversion of discretion by men dressed in little, brief authority. For be you ever so high, the law is above you.”

Justice Krishna Iyer, MS Gill v Chief Election Commissioner

Constituting Democracy

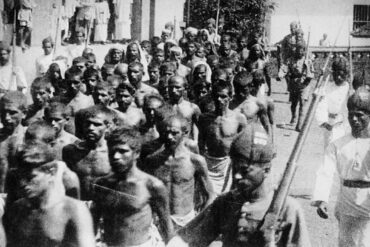

Two revolutions – the national and the social, had been running in parallel in India since the end of the First World War. With independence, the national revolution would end. However, freedom was not an end in itself, only ‘a, means to an end’, said Nehru. The process of social revolution would be long. The assembly wondered if ‘there was not a gong, a single note, whose reverberations might awaken – or at least stir – sleeping India?’

There was: direct election by adult suffrage. In the words of Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar, the “assembly has adopted the principle of adult franchise with abundant faith in the common man and the ultimate success of democratic rule, and in the full belief that the introduction of democratic government on the basis of adult suffrage will bring enlightenment and promote the well-being, the standard of life, the comfort, and the decent living of the common man.”

The Election Commission

Democracy was to be the pillar of the social revolution in India. Free and fair elections are the prerequisite of a successful democracy. The Constituent Assembly bestowed the responsibility of ensuring this on the Election Commission – a body drawing its powers directly from the Constitution.

Article 324 establishes the Election Commission and vests it with the powers of ‘superintendence, direction and control’ of the elections. The Chief Election Commissioner cannot “be removed from his office except in like manner and on the like grounds as a Judge of the Supreme Court.” The provision is meant to ensure that independence of the members of the Commission, and isolate its operation from political interference. The Supreme Court has held that the powers conferred under the Constitution under Article 324 ‘operated in an area unoccupied by any legislation and has to be interpreted in the ‘broadest terms’, including the powers to cancel a poll and order re-election.

Over the years, the Commission has become one of India’s most powerful regulatory bodies. It has overseen the completion of 16 national and 350+ state elections since 1952. At one time (1996), during the Seshan era, it was seen as the most trusted public institution in India.

The Model Code of Conduct

The Model Code of Conduct (MCC) is a set of guidelines issued by the Election Commission to regulate the conduct of political parties and candidates during elections. A form of the MCC was first introduced in the state assembly elections in Kerala in 1960. It was a set of instructions to political parties regarding election meetings, speeches, slogans, etc. In the 1962 general elections to the Lok Sabha, the MCC was circulated to recognised parties, and state governments sought feedback from the parties. The MCC was largely followed by all parties in the 1962 elections and continued to be followed in subsequent general elections. In 1979, the Election Commission added a section to regulate the ‘party in power’ and prevent it from gaining an unfair advantage at the time of elections. In 2013, the Supreme Court directed the Election Commission to include guidelines regarding election manifestos. These were included in the MCC for the 2014 general elections.

The Code was intended to provide a level playing field for all political parties, keep the campaign fair, avoid clashes and conflicts between parties, and ensure peace and order. Crucially, it also seeks to ensure that the ruling party of the day does not misuse its official position to gain an unfair advantage in an election.

The MCC contains eight provisions dealing with general conduct, meetings, processions, polling day, polling booths, observers, party in power, and election manifestos. Under the Code, activities such as use of caste and communal feelings to secure votes, bribing or intimidation of voter are barred. It also mandates that the party in power not use official machinery for electioneering. Thus, ministers must not combine official visits with election work or use official machinery for the same. The party must avoid advertising at the cost of the public exchequer or using official mass media for publicity on achievements to improve chances of victory in the elections. Ministers and other authorities must not announce any financial grants, or promise any construction of roads, provision of drinking water, etc. Other parties must be allowed to use public spaces and rest houses and these must not be monopolised by the party in power.

Enforceability of the Code

The Code does not trace itself to any constitutional or statutory provision. Thus, some see it as less a legally enforceable charter and more a set of behavioural guidelines. There is an opinion in certain quarters for providing legal status to MCC. The Election Commission has, however, taken a stand against granting of such status to MCC.

In practice, the Election Commission’s enforcement of the code has taken two forms. The first is the use of Paragraph 16A of the Election Symbols Order 1968 which allows the Commission to suspend or withdraw the recognition of a political party found violating the model code. The second is directing the relevant district administration to file cases for breach of provisions of the model code which are punishable under other law, for example the Indian Penal Code. Besides this, the Commission is known to censure and warn errant politicians.

A Model Code or a Moral Code?

As we have seen above, the Election Commission is bestowed with wide powers. The Model Code of Conduct is not an entirely unenforceable code. However, the question of enforcement often becomes a question of will. This was seen during the tenure of TN Seshan as Chief Election Commissioner. Seshan towered above all candidates, making his presence felt on all – the government, parties and the people. The MCC was made to operate firmly, sometimes quite absurdly but always, with great effect.

However, as the present elections show, this has not always been the case. Majoritarian governments often oversee conformist institutions. The case of the 2019 general elections has been no different. The code has been violated – repeatedly by the Prime Minister and members of his cabinet. Candidates have asked for votes in the name of religion, caste and even the Indian army.

It is precisely in situations such as these that institutions and institutional safeguards come into the picture. The Election Commission has to ensure that electoral processes do not get clogged by malpractices. It has to see that social hatred – religious or caste – is not whipped up to win elections. It has to implement the electoral rules firmly and ensure a disciplined adherence to norms. As we have seen, the powers are there. At the risk of repetition, it is only a question of will. If rightly enforced, the code is a set of fangs, that can be bared and that can bite. If the head is infirm of purpose, the code can be reduced to dentures for display only. The Election Commission has to make the right choices, to retain public trust in its credibility.

By Sanjay Hegde and Pranjal Kishore

Sanjay Hegde is a Senior Advocate.

Pranjal Kishore is a Delhi-based lawyer.