When Khushwant Singh became the editor of The Illustrated Weekly of India in 1969, he changed the world of magazine journalism in India forever. In its way, what he did with the Weekly, was as important as the change Tom Wolfe, Hunter S. Thompson and Gay Talese wrought in the world of American journalism, with the ‘New Journalism’—which in the sixties and seventies was hailed as a seismic shift in the way news was reported and non-fiction stories were told.

Or let me put it differently. In regard to his impact on the media, Khushwant Singh was Barkha Dutt before Barkha Dutt, Arnab Goswami before Arnab Goswami, M. J. Akbar before M. J. Akbar, Shobhaa De (the magazine editor as opposed to Shobhaa De the novelist) before Shobhaa De and Vinod Mehta before Vinod Mehta. He was, in short, the granddaddy of them all, a man before his time.

When he took over as editor (a job he had already turned down once in order to write his history of the Sikhs), he was fifty-four years old, and knew very little about either journalism or editing. He had worked briefly for All India Radio, and had founded a government publication called Yojana which no one read, so he wasn’t exactly a seasoned journalist or editor. He was exactly what the magazine needed.

At the time, the media scene in the country was dire. Besides the daily newspapers, there was no interesting television or radio, there was no internet, and the Weekly (owned by The Times of India Group), one of the few periodicals that existed, was dull, worthy and little read, although it was a favourite of maamis in Adyar, auntyjis in Karol Bagh and dentists everywhere. He wrote in a column, ‘The Weekly was a mixture of unrelated articles. Some of it consisted of the tittle tattle at cocktail parties given by Parsi dowagers with outlandish names… A few pages were devoted to “They Were Married” and consisted of photographs of newly married couples from different parts of India, all looking very tight-lipped, glum and unhappy.’ Apart from these it had a few pages devoted to children, syndicated features, and other material that was of scant interest to readers.

Its new editor had three clear objectives. He would inform, amuse and irritate. He decided that he would use the magazine ‘to tell Indians about their own country’, and that he would try and provoke and amuse his readers by publishing controversial or humorous articles.

Soon, changes began to appear throughout the magazine. Gone were the grim studio portraits of middle-class newly-weds; in their place were topless photographs of pretty tribal women or semi-clad foreigners on the beaches of Goa. Besides titillating readers with pictures of scantily clad women, he began writing about subjects that he personally found fascinating, such as gods and godmen (whom he exposed), ‘the refined art of bottom pinching’, and ‘the joys of drink’.

As with the subjects he chose to write about, so with the tone he adopted to write about them. He explained his approach in one of his columns: ‘I have never taken anyone too seriously. I have always been a nosy person, forever probing into other people’s lives. I love to gossip and have an insatiable appetite for scandal… I discovered I could exploit these negative traits to my benefit. Readers were amused by what I wrote and asked for more.’ Circulation soared, and went from about 80,000 copies to a high of 400,000 copies.

Khushwant Singh became the most powerful editor in the country and was courted by political royalty, movie stars, sports heroes and celebrities of every stripe who would do anything to be featured in his magazine’s pages. He lapped up the attention, but continued to be his own man for the most part. He also began to write some of the finest journalism of his career, using techniques that were being popularized at this time by practitioners of the New Journalism. Tom Wolfe described it in this way: ‘The basic units of reporting are no longer who-what-when-where-why and how but whole scenes and stretches of dialogue.

Khushwant Singh became the most powerful editor in the country and was courted by political royalty, movie stars, sports heroes and celebrities of every stripe who would do anything to be featured in his magazine’s pages. He lapped up the attention, but continued to be his own man for the most part. He also began to write some of the finest journalism of his career, using techniques that were being popularized at this time by practitioners of the New Journalism. Tom Wolfe described it in this way: ‘The basic units of reporting are no longer who-what-when-where-why and how but whole scenes and stretches of dialogue.

The New Journalism involves a depth of reporting and an attention to detail to the most minute facts and details most newspapermen, even the most experienced, have never dreamed of.’ Some of Khushwant’s work of this time, and a little later (pieces like ‘The Hanging of Bhutto’ and ‘Indira Gandhi’) are stellar examples of this kind of journalistic writing which tried to show readers, in the words of Wolfe, ‘what actually happened’. As the Weekly grew and flourished, young journalists who would in time become stars in their own right (among them M. J. Akbar and Bachi Karkaria) joined its ranks. But the idyll wouldn’t last forever.

In the first major stand that he took as editor, Khushwant Singh blundered. It was a mistake that would haunt him for decades. When Indira Gandhi, the then prime minister, declared a State of Emergency in 1975 that suspended civil liberties in the country, and imposed press censorship, Khushwant Singh offered the move his qualified support. He wrote in a much-discussed essay ‘Why I Supported the Emergency’ that he had an ambivalent attitude towards it.

He supported the clamping down on law breakers (including Jayaprakash Narayan) but didn’t approve of censorship of the press. But his public support of Mrs Gandhi’s action after a cursory attempt at resistance affected him in more ways than one. He was now regarded as an Establishment stooge (in this he was not in a minority of one as several of the country’s top editors behaved, if anything, even more supinely); more damagingly, as an unabashed supporter of Indira Gandhi and her son Sanjay Gandhi (whom he once described as ‘a lovable goonda’), when Mrs Gandhi was voted out of power, he fell out of favour with his employers at the Weekly. Shortly thereafter he was fired, in what was widely regarded as a political move, just a week before he was due to retire.

In one of the most famous episodes of his life, which he has mentioned more than once in his non-fiction, when he learned of his summary disposal, he ‘picked up [his] umbrella, and walked out of The Times of India building’.

Back in Delhi, he began work on a novel, while attempting to (and largely succeeding) in putting his downfall behind him. He looked to Allama Iqbal’s lines to inspire him:

In this world men of faith and self-confidence are like the sun,

They go down one side to come up on the other.

And he did rise again as a journalist and editor, going on to edit The National Herald, New Delhi magazine, and the Hindustan Times, but it was clear that his best days as a magazine and newspaper editor were behind him. However, being Khushwant Singh, he was far from done. Ahead lay a career as a public intellectual and India’s most popular newspaper columnist.

When he was the editor of the Weekly, the renowned cartoonist Mario Miranda created a logo for the Editor’s Page. It showed a sardar seated cross-legged in silhouette with a bottle of Scotch and a pile of books by his side, and a pen and a long ribbon of paper in his hand. The illustration was encased in a light bulb. When he left the Weekly and became editor of the Hindustan Times the light bulb travelled with him to grace his editor’s column; even after he quit the paper (he thinks this was because the mercurial Sanjay Gandhi or his mother did not like an article he had written) he continued to write a weekly column for it; it would become widely syndicated and propel him to the position of India’s leading newspaper columnist.

His columns were a mix of his take on political and other newsworthy items of the day, along with a dash of poetry or personal anecdotes, all written in his signature style (I will look at this in greater detail later in this piece). He said of his column writing: ‘I have no pretensions of being a craftsman of letters. Having to meet a deadline did not allow me the time to wait for inspiration, indulge in witty turns of phrase or polish what I had written.’

Why did the column become so popular? Partly this was because of the lively interest of its author in current events, his astonishing erudition (he read constantly—often fifty or more books a year) that he wore lightly, his wit, his contrariness, but also because he treated the reader as an equal with whom he was having a constant, spirited dialogue. He writes in an article about how he approached his job as a columnist. ‘One should never be pretentious…[one should] be honest and not show off by using difficult words. A writer’s responsibility…is to inform your reader while you provoke or entertain him… Don’t talk down to the reader; level with him.’

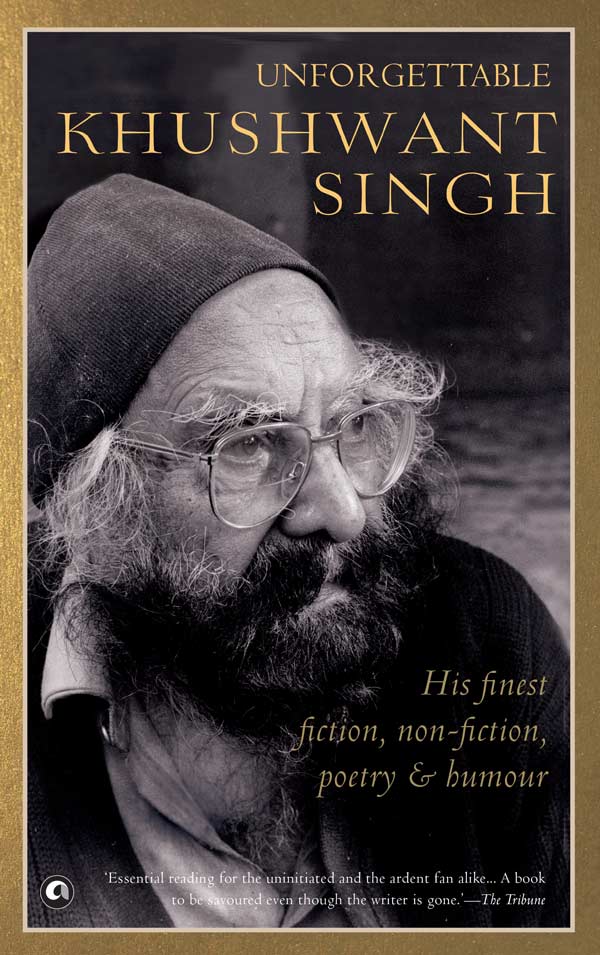

Excerpted from Unforgettable Khushwant Singh with permission