The New Indian Express, covering a wide swath of the south, is in terminal decline, and the closure of a few of its editions would come as no surprise to those who keep track. If anything, I am personally surprised it is still alive. I have particular beef with the unholy nexus between Manoj Kumar Sonthalia, who inherited the southern slice, and S Gurumurthy, the auditor, known for his RSS connections.

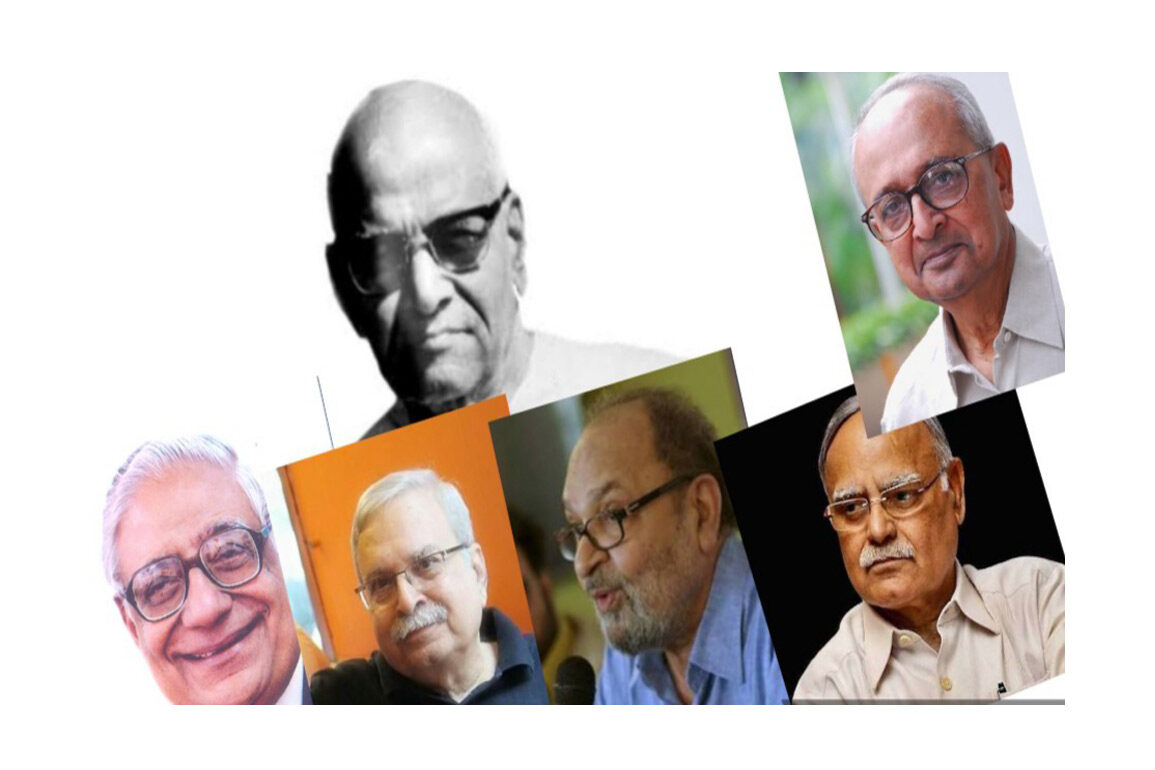

A major calamity for the Indian media was the untimely death of Bhagwan Das Goenka (BD Goenka), son of Ramnath Goenka. Neither the father nor the son was a paragon of virtue, however, Ramnathji had a passion for the newspaper he had acquired. His Emergency saga has been widely chronicled, and he did his best to keep The Indian Express afloat despite the various ills afflicting it.

His son, B D Goenka, was a hands-on man and was ably managing the south, warts and all. BD’s wife, Saroj Goenka, too was an efficient CEO, though no great visionary. In any case she was willing to leave the business of journalism to those she knew it best.

For the brief time she was in charge, the Express continued on its way, not raking in profits, but was not going under either. The system was as chaotic as it used to be, but was also a charming workplace.

Viveck Goenka, a grandson, had been adopted and nominated heir by Ramnathji, it was said, but the old man eventually died intestate, triggering a three-way war involving the two grandsons, Viveck Goenka and Manoj Kumar Sonthalia (MKS) and the widowed daughter-in-law, Saroj Goenka. (Viveck Goenka is the son of Ramnath Goenka’s daughter, Krishna Khaitan, and Manoj Kumar Sonthalia is the son of the other daughter, Radha Devi Sonthalia.)

Viveck Goenka initially took control of the empire and Prabhu Chawla arrived on the scene as the editor, and a pronounced tilt towards the right began. He was angry when I suggested a story on Tamil nationalism: “What Tamil nationalism, Punjab nationalism…there’s only one nationalism, that’s Indian nationalism….” But his reign proved short-lived for the squabbling family arrived at a deal by which the north went with Viveck Goenka and south with MKS. Saroj Goenka herself was cast out, having to content with real estate. Subsequently, Viveck Goenka went on a selling spree, leaving his charge in dire straits, while MKS seemed to be more sober at that stage.

There was this DOT, delivery on time, initiative—in a way it made some sense for the newspaper always reached the landing points way behind others, but tackling the crisis at that end did not. For DOT, many updates were sacrificed, and so much was the DOT obsession, everyone colluded with everyone else to tamper with the records and present a false picture to the higher-ups.

And unlike in the past both the news desk and the reporters had to look behind their shoulders all the time whether anything of what they said would be anti-government (centre or state), for not only would the stories be killed, they could also be censured.

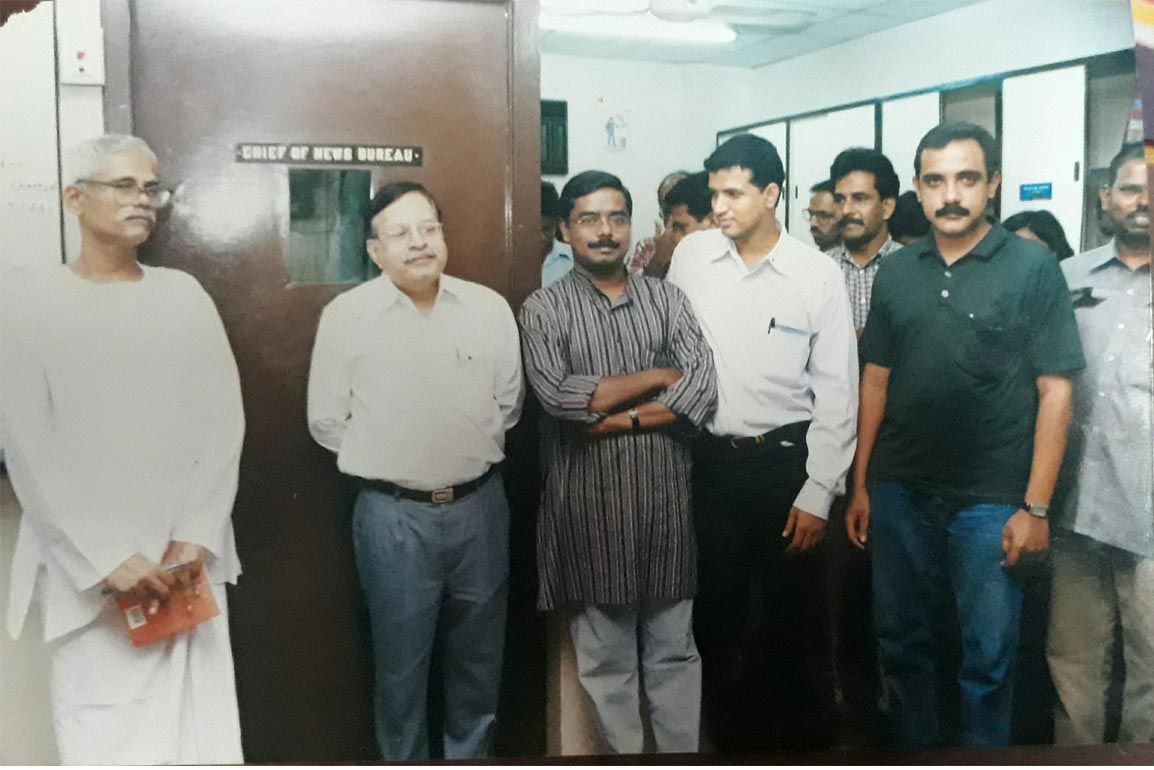

I had been lured back as the Chief of the News Bureau but I found myself stalled at every turn. When the J Jayalalithaa government resorted to mass sacking of its employees, I was asked to write praising the move. I got around by chiding the union employees for prolonging the strike when they knew what was in store for them. To counter that, MKS hosted a gala, Jayalalithaa presiding, during which she was praised for her ‘firm’ handling of the agitation.

Eventually arrears to the state-owned newsprint plant were written off, and the management was happy. Auditor Gurumurthy would be seen having confidential discussions with MKS and in time he achieved his objective—of enlarging his influence.

I had the pleasure of working under Kamlendra Kanwar who was resident editor, Tamil Nadu. He was the very epitome of dignity and affability. He treated his colleagues and subordinates with respect, rarely would he shout at anyone for anything, even though he was always implementing MKS’s firmans with alacrity. He tried to strike a balance between the management’s demands and genuine professionalism. Sadly he found himself reined in all the time, and he had to leave. I had preceded him by a couple of years.

I would like to think it was Saeed Naqvi who infused a sense of professionalism and aggressive reportage during his stint as editor of the southern editions. He encouraged youngsters (including me), besides authoring some splendid pieces that would stand the test of time. I still remember his delectable piece on Malappuram, carved out to humour the Muslim outfits, no ill-will, but expressing his concerns over the encouragement to communal politics.

Anyway Naqvi got caught up in management politics and took on Arun Shourie in the open. Unfortunately Shourie outmaneuvered him easily. Naqvi, who was eyeing editorship himself, had to leave.

H K Dua I don’t remember much, but B G Verghese, who comes in for so much praise in the previous piece here, might have been a good, decent guy by himself but was very much a ‘statist’ and his views always Delhi-centric. He denounced the separatist struggle in Sri Lanka editorially, without any disapproval of the oppression of the Lankan Tamils, kicking up a furore. Some of us chose to write a joint letter deploring his perspective, but nothing came of it. Only we were not taken to task.

Decades have gone by, and what’s MKS’s own vision? Difficult to say. Whatever the havoc wrought by Viveck Goenka at one stage, the northern editions, now under the editorship of Raj Kamal Jha, is keeping the Express flag flying, almost in its old glory.

But such abstract things as legacy don’t seem to attract the other grandson much. In the eighties when The Hindu was on a modernizing frenzy, installing state-of-the-art machinery everywhere, one would be appalled by the smudgy pages of The Indian Express. It was an MKS-owned factory that was supplying the ink, and none could do anything.

Such was the perversity of the squabbles after Ramnath Goenka, MKS wouldn’t pay rent to Express Estate—the premises the newspaper had been quartered in, at the heart of the state capital. Eventually, the newspaper was evicted and had to move into another building way out in the suburbs, bringing in a lot of more complications.

Nowadays the management doesn’t seem to care one way or the other, more editors and bureau chiefs have come and gone, credibility, reputation, everything took a big hit, as of course did the circulation, and the newspaper is now thriving almost solely on government ads.

Does anyone care about the southern slide of the Express?