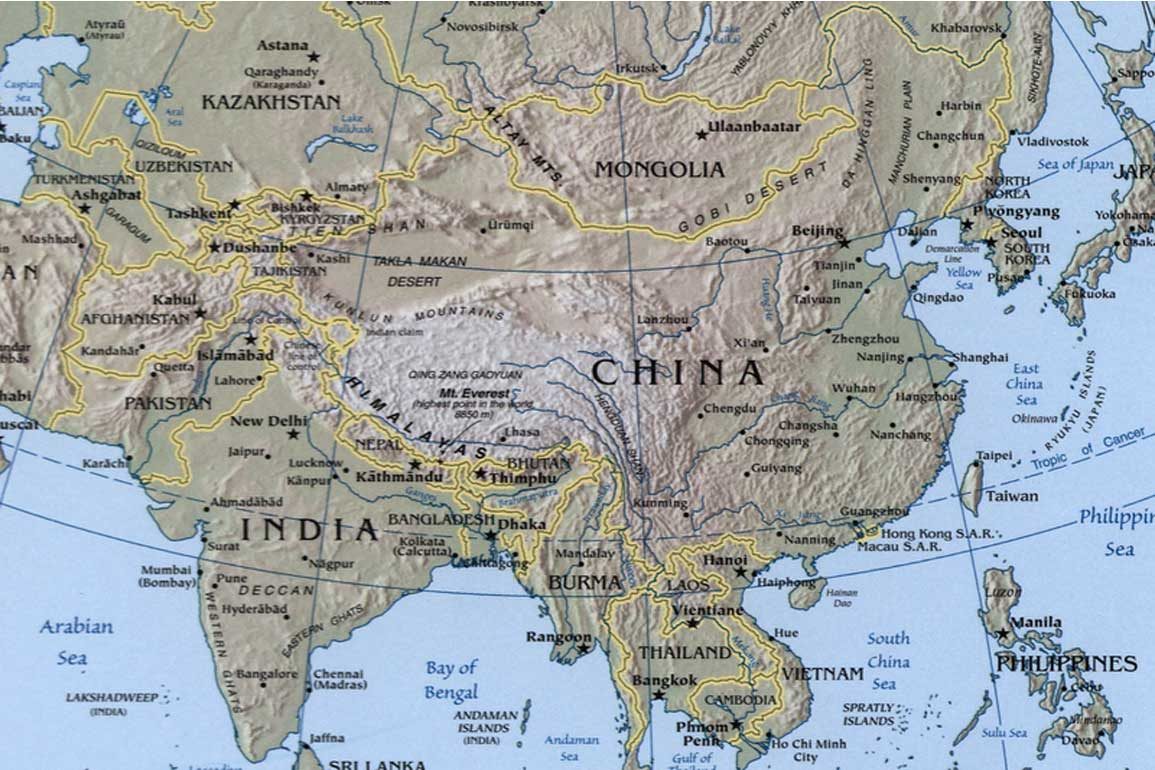

Let me start with the Himalayas. What did that mountain range do to India and China, the only two countries that hold a billion people each? Well, the high mountains never left a trace of similarity between the cultures of people on both sides, despite sharing a 3488-km-long border including all the three sectors in the west, middle and the east. Moreover, the Chinese heartland lies far away to the east where majority of the population lives. It is in these harsh Himalayan frontiers that new tensions are heating up between the two Asian giants, since the past one month.

This was not always the case; not until Tibet, the ‘roof of the world’, was stripped off its independent status using arbitrary military force, and forcibly merged with China. Tibet was once a buffer state between India and China during the British Raj, but it was annexed and made a part of Mao’s People’s Republic China (PRC) in 1950, against the collective will of the Tibetan people. This led to an uprising by the native Tibetan population and in the same decade, Tibet’s spiritual leader – the Dalai Lama – fled to India and established a government-in-exile.

The next decade saw India fighting a war with China over a part of the erstwhile Jammu and Kashmir state – the Aksai Chin region – which was hitherto part of India, and Tibet’s political status being changed to one of the Autonomous Regions of the PRC. So, how did things change after all these turn of events, for India and for China, in the military, security, and diplomatic fronts, and what is all about the present ongoing tension at the borders?

An overview of the borders in the light of the current face-off

Today, the Indian Union Territory of Ladakh and the states of Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Sikkim, and Arunachal Pradesh share a border with Tibet, and in effect, with China. Additionally, Ladakh also borders the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, the only Chinese province other than Tibet that India shares its borders with, via Aksai Chin.

Since the first week of May 2020, the two Asian giants have locked horns in the western and eastern sectors, along the Line of Actual Control (LAC). However, the middle sector, bordering Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand, remains mostly peaceful. In the eastern sector, there was a scuffle in Sikkim’s Naku La pass in the second week of May, this year. Days before this, the Pangong Tso Lake region in the Ladakh sector also witnessed a clash between the Indian and Chinese troops, reportedly the first in the series of instances that occurred in May. The boomerang-shaped lake is strategically located along the disputed border that goes right through its middle, with China controlling two-thirds of the lake region, de facto. It also has a memory of China attacking via this route during the 1962 war.

However, this time, the most serious of all clashes happened in the Galwan Valley, lying between Ladakh and the disputed Aksai Chin region where the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) of China has moved in hundreds of soldiers from their border regiments close to the LAC. Some media reports even suggested that stones were pelted at each other by the Indian and Chinese soldiers, and that the PLA used ‘unethical and unprofessional’ means like injuring their Indian counterparts with sticks, clubs, and barbed wires as the face-off turned ugly. The PLA was also large in number as Beijing had sent extra troops to the borders, the same method they employed in the 1962 war.

The disputed Aksai Chin is claimed by India as part of Ladakh, and China as part of the Xinjiang. This region is de facto controlled by China, and has been used by the PRC to connect Tibet with Xinjiang by building road networks since the 1950s. India maintained control of this region until the end of the 1962 war, after which China occupied it. India claims that China now occupies 38,000 km of its territory. In the 1990s, both countries agreed to respect the Line of Actual Control (LAC) as the de facto border.

At the end of May, the Naku La clash at the eastern sector has calmed down. But, the western sector (Ladakh) remains tense. Anyway, all eyes of the media, commentators, geostrategists, diplomats, and scholars are on the Ladakh sector. In a first official response from the government since the face-off began, India’s Defence Minister Rajnath Singh on May 30 said that the issue will be resolved through bilateral dialogue on both military and diplomatic levels.

This is the fiercest face-off between India and China in many years. Chinese President, Xi Jinping, has apparently ordered the PLA for battle preparedness. Indian PM Narendra Modi has also reportedly discussed ground situation with the army top brass in a high-level meeting. So, what are the circumstances and background that has led to this current face-off?

Renewed border infrastructure build-up

Earlier, it was common for both sides to cross the loosely-demarcated LAC and it was solved at the local level by the military itself. But this time, it has been escalated by both sides using new infrastructure such as new roads and bridges. Both countries are now building up infrastructure to facilitate rapid movement of troops and to catch-up with modern weapon systems. But, there is no denial of the fact that there exists an asymmetry in terms of both troops, and the military and technological capabilities.

According to a recent report by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), a Stockholm-based think tank, China and India are the world’s second and third largest military spenders in 2019 respectively, only behind the United States. Both the countries have increased the percentage of their military spending from the previous year. China’s Communist Party-dictated state policy has always given top priority building infrastructure all across its strategic borders. And, India’s renewed vigour to build roads like the 255-km Darbuk Shyok Daulat Beg Oldie (DBO) road that was completed last year, and other new infrastructure developments has certainly annoyed China. India also wants to build new feeder link roads and bridges over the mountainous terrain of Ladakh, which the Chinese do not like. Security analysts have attributed this as the gradual build-up to the May face-off.

The fact that the LAC is not fully demarcated even today in certain parts adds up to the fresh tensions. The Chinese believe that its border with India is only 2,000 km long, but India estimates it to 3,488 km. Currently, only 35 of the 73 strategic all-weather roads identified for construction two decades ago have been completed so far, and India has resolved to move ahead with all its planned constructions.

‘India not the same as it was in 1962’

Three years back, India’s former Defence Minister, Arun Jaitley, had responded to a Chinese statement that asked to learn from ‘historical lessons’ with strong words, “The situation in 1962 was different, and the India of 2017 is different”. In 2020 this is more and more evident. Today, both the countries know very well of their military capabilities. Still, skirmishes at the borders followed in August 2018 in Ladakh’s Demchok and even in September 2019, a month before the Chinese President’s visit to India, in Eastern Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh.

Indo-China Diplomacy

April 2020 was special in the diplomatic history of India and China as both countries observed 70 years since the establishment of formal diplomatic relations. Marking the event, diplomats and leaders of both sides have even exchanged congratulatory messages and re-affirmed their will to co-operate during the pandemic.

In fact, looking back at history, India under Jawaharlal Nehru was the first non-communist Asian country to recognise the Mao’s People’s Republic of China and to establish diplomatic links with it seven decades back. Both countries framed and adhered to the Panchsheel principles of peaceful co-existence until the 1962 war when India was humiliated with a surprise and asymmetric attack. Still, India still considers the war as a betrayal by China. Years and decades have passed. New leaders came and went on both sides, and military arsenals expanded. In the course of time, India was also declared a nuclear state, making it the first non-P5 state to achieve the feat.

In 2017, the Indian and Chinese troops sparred again, positioning themselves ‘eye-to-eye’ in Doklam, the Sikkim-Bhutan-Tibet tri-junction, and the subsequent stand-off lasted for 72 days. As tensions were eased, two informal summits were held in the following years as a means to re-build confidence between the leaders of both countries – Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi – one in Wuhan, China (in 2018) and the other in Mamallapuram, India (in 2019).

Xi’s bid to divert attention?

During the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, both countries supported each other by providing essential medical supplies to both sides. Despite all these measures, the situation at the border is stripping out of the hands of bilateral diplomacy. Meanwhile, an offer by US President Donald Trump to mediate on the border face-off was rejected by both India and China.

Earlier, China faced an international backlash for downplaying the seriousness of the coronavirus pandemic, and has suffered economically too, at home. Many companies have expressed their willingness to shift their business out of China to other countries like India. All these turn of events have damaged President Xi Jinping’s goodwill at home, and many security analysts believe that by creating a tense situation at the border, and by preventing India’s routine infrastructure activities, public attention can be diverted from its own governance failures.

The Union Home Minister, Amit Shah, in a recent television interview, said the issue won’t be taken lightly and India won’t compromise a bit. Meanwhile, the US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo has taken a dig at the China for perpetuating the conflict. Social media in India has also gone into a frenzy with campaigns to boycott Chinese products and applications.

Even though China has a definite military advantage, an escalation of the current face-off between two nuclear-armed neighbours definitely wouldn’t be in the interest of its citizens. A complete de-escalation of tensions requires strong political and diplomatic will at both sides, along with the troops retreating to their previous patrol positions on the ground.

As the military stalemate continues, all eyes are on the diplomatic talk currently underway between the Indian and the Chinese Foreign Ministries. The much-awaited military dialogue between India and China scheduled on June 6, led by lieutenant general level rank officers from both sides, can hopefully rebuild confidence and possibly lead to a mutually agreed resolution.