While the world is battling the dreaded Coronavirus, Kerala State and its Health Department have already earned plaudits for the efficient way it has handled the ongoing crisis and for its proactive and decentralized approach to flatten the curve. As it stands, Kochi is in the green zone and life is coming back to normalcy albeit with some permanent changes in lifestyle that could change the world as we know it.

Let’s take a look back into the annals of time in erstwhile Cochin State and its public health care system, facing its own challenges, what was done to combat deadly diseases and to keep check on the public health of the people.

Kerala, the land of Ayurveda was always remarkable for its herbalists who were well versed in herbal science. Ashtavaidyans enjoyed a great reputation for their skill in curing the thousand ills. Namboodiri Vaidyans prescribed decoctions, mixtures, electuaries, powders, pills and oils made from medicinal herbs found deep in the forests. Every village is said to have their own hereditary hakims and midwives. Few of the Cochin Maharaja’s themselves had sound knowledge in Ayurveda; but they also gave their keen support to western medicine.

Not much is known about the state of public health before the advent of the Portuguese. With the arrival of the colonials, we find the beginning of the first known public ‘hospital’ in Cochin. The book The Survival of Empire-Portuguese Trade and Society in China and the South talks about “The first ‘Santa Casa da Misericordia’ in Asia was established at Cochin in 1505.” It was a Lisbon based charitable institution that provided medical help and looked after the poor and destitute. The first of its kind in Asia. This was only a few years after the Portuguese fort was built in what is now Fort Cochin. By 1522, amongst the towering manueline churches, religious schools, the famous three-storey library and homes, the Santa Casa da Misericordia had its own building within the fort and was named as ‘Cruz de Cochin’ after the city of Santa Cruz.

In Dutch times more than a century and a half later, archival records suggest there was a hospital within the Dutch fort, catering to patients on the basis of the posts they held in the Dutch East India Company. This was not open to the general public though as the Dutch wanted to keep it strictly for business purposes. There are records of a Mohammedan sailor who was admitted but no one outside of the VOC. Archival records and later English writers suggest that this hospital existed somewhere near the Dutch cemetery towards the south-western side of the fort. But when the British took over they blew up almost all the stately buildings in the fort and the hospital was collateral damage.

Moving away from the fort in Cochin to another one a couple of kilometers away. At Palliport (Pallipuram), the Portuguese maintained a leper hospital called the ‘Lazaretto’ or ‘Lazarus House’. This was an isolation hospital for people with leprosy who had to live a life of isolation for the rest of their lives. When the Dutch took over, they owned and controlled this leper hospital. Much later, the Cochin State opened a leper’s hospital in Venduruthy Island.

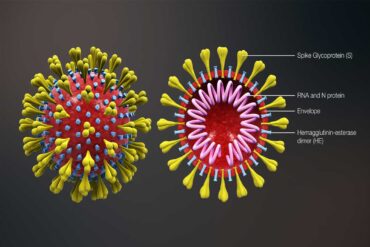

Deadly diseases had its effects in Cochin like elsewhere across the globe. Smallpox was widespread and dreadful in the entire Malabar region including Cochin and Travancore with at least four major deadly attacks in the 19th century. Newborn and young children lost their lives due to the disease and whenever it broke out within the state, it was utterly devastating to the population. Cholera was rampant for a very long time but not as dreadful as smallpox. There was an outbreak of plague in Mattancherry in the 1930s but prompt measures were taken to combat the disease. Filariasis or Elephantiasis was another scourge for the people of Cochin owing to the unhealthy living conditions and unclean drinking water and it ended up being called the ‘Cochin Leg’. Drinking water was then subsequently brought in from Aluva and Varapuzha by the Portuguese which was continued by the Dutch at a cost and the English after them. This water from the Periyar River is said to have medicinal properties and was used as curative by people from all over the land, a precursor to medical tourism.

To tackle these endemic diseases, the state took it on themselves to introduce vaccination in the state as early as 1802. Old records from the Munro administration mention a pay bill for vaccinators. These facts show us that the Darbar was concerned in matters affecting the public health of its citizens. But great progress on this front was not made because the people dreaded vaccination sometimes even more than the disease itself and had no faith in western medicine. For a very long time, vaccinations were looked down upon by the majority of the population. It was towards the latter part of the 19th century when people started to get educated that vaccination as a remedy to prevent diseases was recognized by the general public.

Colonel Munro was the British Resident and first Diwan of Cochin who brought in a lot of new measures and reforms which were implemented by the Cochin sirkar. This included a grant from the sirkar to introduce western medicine in the State. A certain CMS missionary by the name of Thomas J. Dawson was posted in Cochin and he set up a dispensary in Mattancherry right about in 1818. But ironically he had to leave due to medical issues and the effort was short lived. However, it did open up decades later. The Government Dispensary in Mattancherry was opened in 1853 and was located where the Government Taluk Hospital Headquarters in Fort Cochin now stands. When Fort Cochin became a municipality, this became the Municipal Hospital. The locals still call it the ‘Fort Hospital’ or ‘Kotta Ashupathri’.

Francis Day, a civil surgeon and medical officer who served in the 1860s to the royal darbar, points out in his book, Land of the Permauls, that the civil surgeon was appointed in May 1817, and under him two subordinates. One stationed at the Dispensary, and another with the jail to attend to prisoners. The civil surgeon continued to be in charge of the medical department till 1895, when a full time chief medical officer was appointed as its head.

Sanitary Boards were established in 1896 for Ernakulam and Mattancherry. At the turn of the 19th century, major cities like Bombay, Madras, Mysore and some districts of the Madras Presidency battled the plague of 1897. The State decided to have Inspection Stations called ‘Pass-port Stations’ and observation circles at the port to prevent the disease from spreading from sailors. The Cochin Chamber of Commerce taking cognizance to the civic needs of the town extended generous support and appeals during these times. One such appeal was from the Municipal Chairman of Fort Cochin in 1897 for monetary assistance to enforce quarantine regulations against the passengers arriving from Bombay who were affected by the bubonic plague. In 1910, the sanitary department was again reorganised into the Department of Public Health under the control of the Chief Medical Officer. Sanitary Inspectors were appointed who were made responsible for vaccination, fairs and festivals and epidemics.

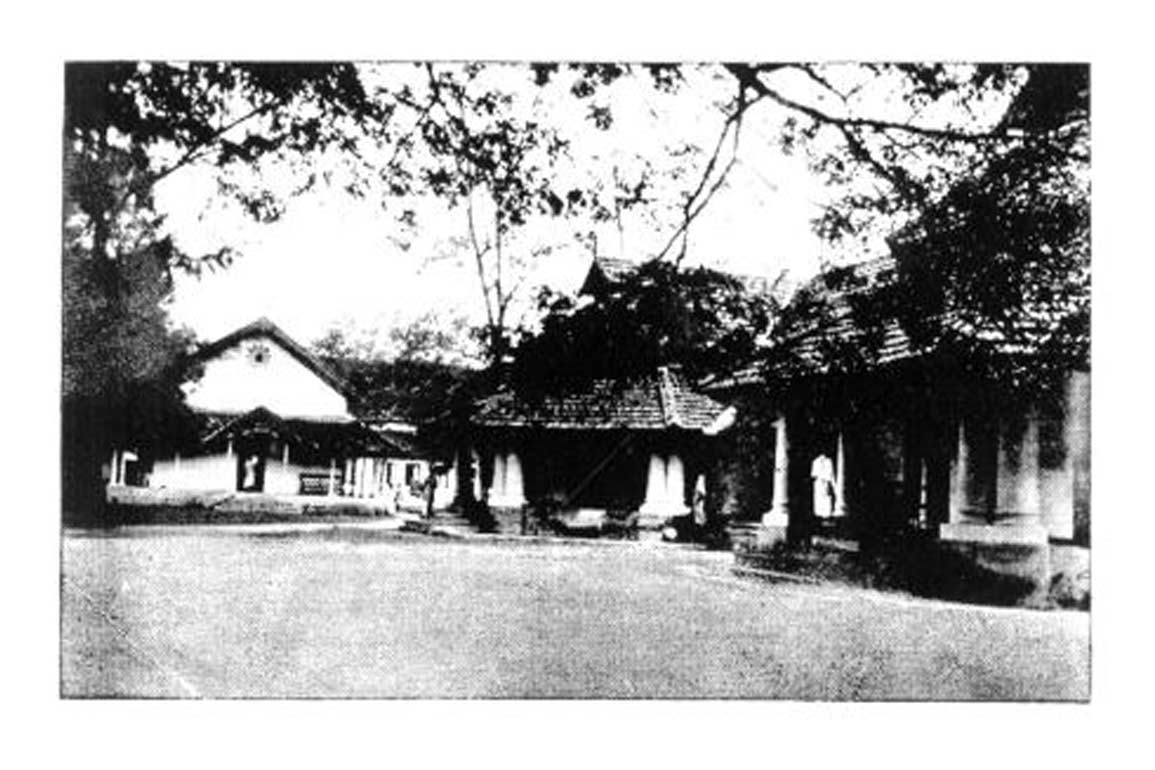

Government Hospitals were mainly preferred by the affluent and the poor, the former because they could pay and the latter because the treatment was free. The middle income group always preferred to consult indigenous practitioners of various disciplines like allopathy, homeopathy and so on. When the locals demanded for a hospital in Ernakulam, the British were hesitant. Finding it to be a beneficial request, it was the Raja of Cochin who decided to establish a dispensary in Ernakulam. Diwan Sankara Variyar entrusted with this, opened the dispensary in 1848, which was called the ‘Charity Hospital of Ernakulam’. It was barely anything but was a good start. What started in a small thatched house, later developed into the General Hospital of Ernakulam. The hospital had the reputation of being one of the most efficient hospitals in South India bringing people from nearby states for treatment. When the British finally sanctioned the hospital, it was partly funded by the locals themselves. Francis Day writes, “The inhabitants of the town subscribed 1768 Rupees, and the Government contributed the remainder: the total cost of the building, being 4517 ¼ Rupees”.

After the 1880s, hospitals sprang up in Trichur which was under Cochin State, Tripunithura, Mattancherry, Andikkadavu and Njarakkal. As the years went by, due to its growing popularity and demand, there was a need to expand the hospital in Ernakulam. And in 1882, a new hospital building was built where the General Hospital now stands. The old hospital was converted to the Munsiff’s Court.

Stories abound about the hospital. There is one particular story mentioned by the Maharaja Rama Varma (Ozhinja Valiya Thampuran or the Abdicated Highness) in his autobiography about the X-ray apparatus. The apparatus at the hospital was brought in by the Maharaja for the treatment of his mother who had a diseased leg. Since the apparatus was in vogue at the time, the Raja found it useful to give it to the hospital. When the then Diwan asked the medical officer Dr Coombes if he could find any use of the apparatus, the doctor replied that he couldn’t find any. Which was baffling. The Raja then paid for it from his pocket and had it kept in the hospital and this marked the beginning of X-Ray in Cochin.

By the 1930s, the General Hospital had a dedicated X-Ray Department, an ophthalmic hospital which was inaugurated by Lord Willingdon on his visit to the state, an isolation ward, anti-rabic treatment, nurses quarters and electricity. With the arrival of the world class port at Willingdon Island, the Cochin Port Trust opened up a hospital on the island as well. Private hospitals began to emerge in different parts of the city in the early decades of the 20th century. Since Independence, the General Hospital of Ernakulam has become the first government hospital in the state to be accredited by the National Accreditation Board for Hospitals and Healthcare providers (NABH). On the other hand, a dedicated hospital for women, the Women’s and Children’s Hospital in Mattancherry was opened as early as 1893 with a woman civil surgeon and this runs to this day near the Mattancherry Palace.

The year 1949 brought the merger of the states of Cochin and Travancore. Both states were already progressive in their approach to the general health of its people. Today, Kochi has an abundance of general hospitals, speciality hospitals, super speciality hospitals, medical colleges both private and by the state. The small princely state of Cochin has come leaps and bounds with its progress in medicine and surely we are on a road to good health.