The 80th session of the Indian History Congress became part of the long and passionate battles being fought in the field of Indian historiography with two streams of thought facing each other in an epic intellectual confrontation. This time, it took the form of a direct skirmish between votaries of two antagonistic views of history even at the inaugural session of the Indian History Congress, which had so far remained aloof from the raging internal ideological squabbles.

What is at the core of these differences was highlighted in the open stage confrontation between the Kerala Governor Arif Mohammad Khan and eminent historian Dr Irfan Habib: When Arif Mohammad Khan quoted Mualana Abul Kalam Azad out of context in his speech, Irfan Habib took objection and, rising from his seat, asked the Governor to quote Gandhi’s killer Nathuram Godse instead of the erudite nationalist who fought the ideologues of the two-nation theory at the time India’s partition.

It was a quirk of history that these two brilliant members from the Muslim community in Uttar Pradesh should face each other at the Communist bastion of Kannur in Kerala over an issue that has divided both these individuals as well as the country for long. Arif Mohammad Khan had his political career cut out as a reformist in the Muslim community at Aligarh Muslim University where he was president of the students union in early seventies, when Irfan Habib served as faculty as one of the most prominent members of the history department. Arif then went on to become a prominent member of the Congress party, holding a position in the Rajiv Gandhi cabinet, which he left in 1986 in protest against the legislation overruling the Supreme Court order in the Shah Bano case which upheld the Muslim woman’s right to maintenance after divorce. His battles with the conservative sections in the community eventually took him to the Bharatiya Janata Party in course of time.

Habib, on the other hand, remained at Aligarh historians’ group as a prominent theorist and scholar, emerging as one of the best-known Indian historians on the Mughal period, an area of research that had made his father Mohammad Habib the most prominent historian of an earlier generation. Habib, a Marxist historian close to the Communist Party of India (Marxist) leadership, became an important figure of the country’s academic establishment in the field of history as chairman of Indian Council for Historical Research (ICHR) and one of the leading lights of the Indian History Congress, launched by a group of nationalist historians at Pune in 1935.

The confrontation at Kannur University was the latest episode in a series of long-drawn battles that have been going on in the field of historical research and teaching, beginning with the early seventies. The point of dispute has been the critical issues that divided India’s national movement: What defines Indian nationalism? The dominant view was that India’s national identity emerged as a composite secular entity evolved through the many decades of national movement and anti- imperialist struggles that drew all sections of Indian society irrespective of caste, class, creed or region into its fold like a vast crucible that encompassed the whole of India. That was the narrative of India as a secular nation.

This idea of Indian nationhood has been challenged by the right-wing nationalists who defined India as a Hindu rashtra, a political idea that inspired the principal challenger to the dominance of Congress party in Indian politics. In the days of Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi, the Bhartiya Jan Sangh—the political party that epitomised this Hindutva ideology—was only a fringe player. But things took a different shape ever since the BJP emerged as a contender for power in the late nineties.

In all these years, history remained a real battle ground, because the Hindutva forces were aware that without a comprehensive rewriting of Indian history, the Hindutva project would remain largely unfinished and illegitimate. Hence the constant efforts to take control of the Indian History Congress (IHC), the supreme body for India’s historians for the past many decades. The significance of the IHC as an academic ensemble is evident in its long history with its roots in the national movement, its vast membership that encompass the entire spectrum of Indian historians young and old, and also its annual sessions that travel from university to university in every part of India during the concluding days of each year, bringing together the best minds of Indian history within and outside the country at its venues.

The Sangh Parivar’s effort to wrest control of the IHC was a move that has not been successful, because its votaries could never match the intellectual eminence or the scholarly achievements of secular historians like Romila Thapar, Bipan Chandra, Irfan Habib and others who led the Indian History Congress, giving it a clear perspective against the clouded and confused views of the Sangh brigade whose efforts to produce an alternative historical narrative were dubbed by professional historians as ‘manufactured history’ which sought to replace facts with fables.

The confrontation between these two groups came to a head in the late nineties when the Human Resources Development (HRD) ministry in the Vajpayee Government took steps to revise and rewrite the history textbooks for the CBSE schools. These textbooks were prepared by the NCERT with the help of prominent historians from universities like the JNU and were generally hailed as some of best examples of history writing for the young generation. The Ministry compelled the NCERT to revise the books, but when they were released, these books were found to contain so many howlers and factual errors that left the government red faced. In fact, it was a committee of experts set up by the IHC that brought out two volumes that critically examined the new textbooks exposing the fallacies they contained.

Another round of confrontation took place over a prestigious project of the Indian Council for Historical Research (ICHR), which had undertaken to bring together the entire set of documents relating to the national movement into a series of volumes called, Towards Freedom. In 2000, the ICHR announced its decision to stop publication of two volumes relating to the crucial period 1937-47 edited by eminent historians Dr Sumit Sarkar of Delhi University and Dr K N Panikkar of JNU. This created a huge controversy because the editors charged the RSS of interfering in its publication because they found that these volumes “exposed their lack of any major role in India’s freedom struggle” as they thought the Muslims were the primary enemies of India’s Hindus and not the colonial rulers. Sumit Sarkar, son of the legendary Bengali historian Susobhan Chandra Sarkar, has been a prominent figure in the Indian History Congress who opposed the Sangh Parivar’s moves to rewrite Indian history. Dr K N Panikkar has been known as a Marxist historian opposed to the RSS and its divisive ideology.

In all these battles, it was Dr Romila Thapar, India’s most illustrious living historian, was singled out for relentless Sangh Parivar attacks. In a controversial move, the authorities at the JNU, where she still serves as an emeritus professor, asked her to furnish her bio-data in case she wished to continue in her role. She was vilified in the book Eminent Historians authored by Arun Shourie at a time when he was one of the prominent members in the Vajpayee Government, dubbing her work “anti-national” for her role in defending India’s secular institutions like ICHR from government interference.

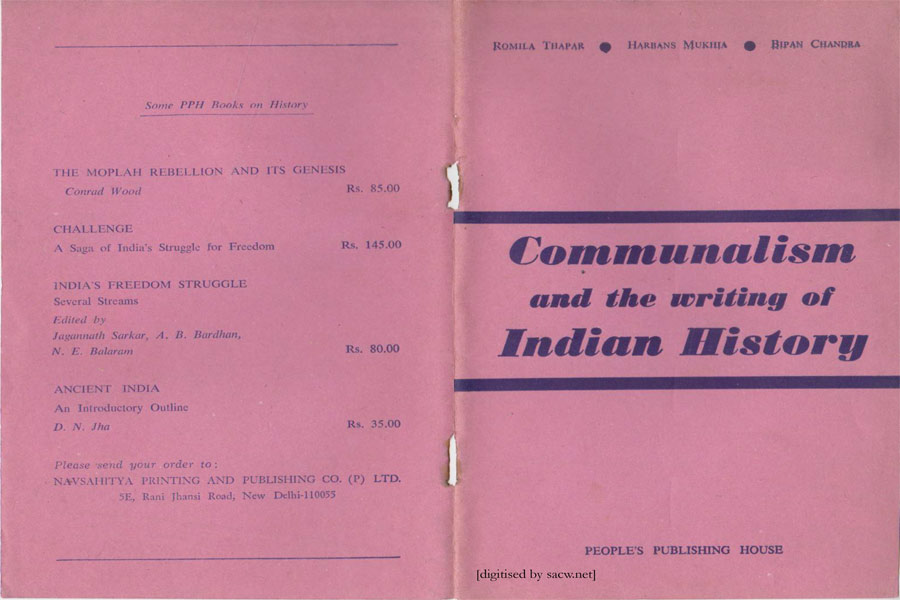

In fact, the attacks on Romila Thapar reflected her eminence as India’s most authentic historian. She was one of the first historians to take up efforts to defend secular India, with the publication of the pamphlet, Communalism and the Writing of Indian History, way back in 1969. This volume brings to the focus the dangers of communalising the writing of national history, with Thapar dealing with the problems of history writing on ancient India, Dr Harbhans Mukhia about the issues concerning medieval Indian history and Dr Bipan Chandra on the same questions with regard to modern Indian history. The slim volume gave the first clarion call to defend Indian history against falsification from a communal point of view.

The confrontation still rages on and the episode in Kannur is the latest—but surely not the last—in an epic battle for defining India and its nationhood.