The beauty that fills within as you think on. —Narayana Guru

How can you talk about culture and politics not in terms of the other? As otherizing and demonizing boom in the jingoistic contexts of monolithic cultural and linguistic nationalsim and regional elitism; the representation of the other becomes central in cinema and semiotic narratives. Othering and exclusions are happening in film festival selections through selective representations or erasures. It has been there in IFFI (International film festival of India) from the beginning of this century and now in the last few years such hegemonic tendencies have crept into IFFK (International film festival of Kerala) too.

Monopoly groups and over-represented cliques are repeatedly celebrated and canonized while critical and radical films are marginalized and out-casted. De-centering and de-canonization are urgently required at this critical juncture. It is high time that the ruling elite of the film academia and related media listen to other voices, see the other visions and examine their own omissions, myopias and evasions.

If the constitutional ethics and democracy are shattered nothing would remain in India—the land where the entrenched Vedic Varnashrama dharma is resurging through repeated Smriti-Sruti-Puranas and their re-articulations by leading pundits and aesthetes both in the left and right. The Hindu rhetoric and semiotics are further alienating the other creating outcastes of the Nation by eventually canceling their citizenship and making concentration camps in remote corners of the country. The killing caste must be reckoned beyond religions. The religion of caste needs critical identification and deconstruction along with the inter-sectionality of gender, region, religion and sexuality.

The exclusionary hegemonic narratives of othering must end and ethical and egalitarian articulations of inclusion must begin as the Buddha and Guru imagined. Only fraternity, equality along with liberty could make such a human space in a democracy. The voices and visuals of dissent that are prudent and futuristic must be acknowledged and represented in a plural democratic society. It destabilizes the status quo but delivers posterity from conventional ignorance. An aesthetics and politics of compassion and ethics at large must be encouraged in cultural realms.

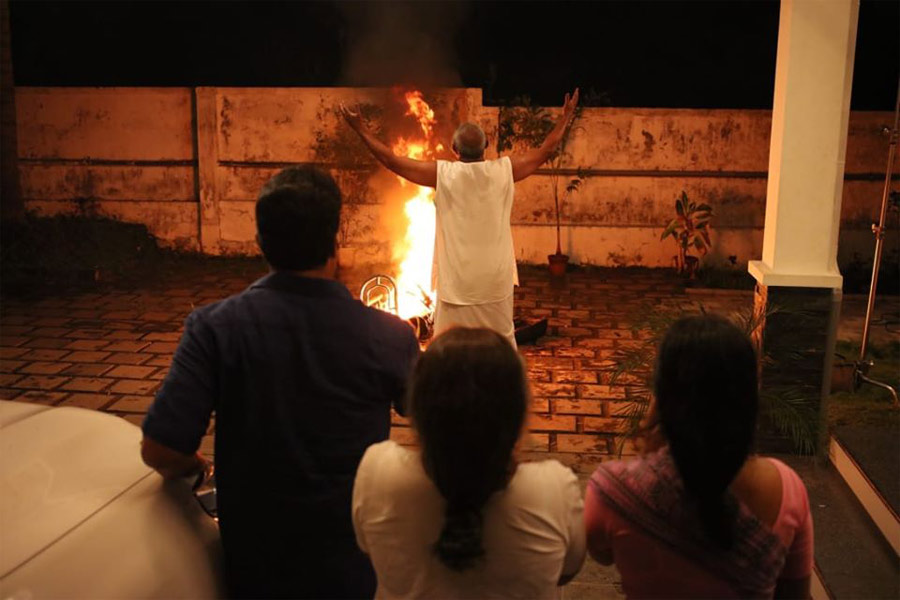

At the IFFK, there are some filmmakers who are acknowledged but still some remain outcasted. The fear of the other voice and vision is a totalitarian and fascist trait that must be acknowledged and corrected. In the compassionate and egalitarian ethics of India and Kerala in particular, the other is equal in all respects. The filmic attempts by Dr Biju or Priyanandan or Salim Ahmed in Kerala cinema gain importance here. The excluded also speak louder for sheer denial of opportunity and by the marked prolonged absence. The new film, Chola, by Sanalkumar Sasidharan running in theatres for a month now, proves the point brilliantly.

Dr Biju addresses the basic reality of social inequality in Kerala as well as in the Himalayan fringes in Veyil Marangal (Trees under the sun). The genocidal casteist untouchability and its paganistic roots need to be filmed and exposed further in micro-political detail along with the inter-sectionality of gender and religion. Priyanandan explores the racist and capitalist patriarchal core of the communal elitist nexus in Kerala through an oedipal father-son-mother queer triangle in Silencer. The silences and evasions of the mainstream caste Hindu consensus that is absorbed and appropriated into the mainstream minority discourse that makes it dominant and racist is subtly alluded to and exposed poignantly in the artful scenography by poet P N Gopikrishnan.

The other in human conjugal relations, self motives and interwoven desires are the visual concerns in Shyamaprasad’s A Sunday. But the social and political question of propriety and context are more crucial in the barbaric premise of annihilation and gas chambers in the country and increasing events of lynching even in Kerala. While in Unda, Khalid Rahman makes a late and desperate filmic depiction of the current-socio political crisis by touching upon the tribal and militancy issues, in the movie And the Oskar Goes to, Salim Ahmed pushes his frames to the possible and desperately hopeful. Perhaps only Malayalees who believe in the status quo are able to cherish hope in the days of violent annihilations of the other, say critics.

Cinema as a dialogue and engagement with the other and less represented moves on in times of annihilation and sanctioned blindness. Let us hope for a future cinema of ethics and compassion as some of the casted out films signify in silence. Also it is imperative to listen to the criticism that popular box office hits are getting increasingly over represented in Indian festival circuits and this will have an impact on the choice for global international arenas and their mode of selection. Hits achieving blockbuster status and record collection may be kept out as proper commercial films and more radical and experimental stuff by new aspiring directors should be included and showcased at least in Kerala.

The process of selection, committee constitution and academy office bearing etc… must be made more transparent and democratic with constant change in power and positions. It is nobody’s private property or feudal inheritance but public money that comes through the constitutional ethics and equality paradigm. Ensuring diversity and internal democracy of representation and inclusion with the egalitarian ethics is fundamental.

Indian vernacular cinemas in various languages represent the growing intolerance and exclusions in the country in various subdued ways. While encounter killings, police firings and custodial deaths are growing in the country the Marathi film Crime No 103/2005 or Mai Ghat by Ananth Mahadevan makes for crucial viewing. The custodians and keepers of the law are misusing it to deny the legal and constitutional rights of the people. Torture and mutilation or even killing are regular now. It is like being more English than the English or the Sudra acting more Hindu than the Brahmans if we invoke the classic case of caste in India.

The democratic fabric and constitutional culture and its legality are under extreme threat. Human rights violations and legal rights denials have become normative. The constitution itself is under selective abrogation and erasure. Constitution was symbolically suspended when the “economic reservation” amendment was passed in early 2019 and implemented in service recruitment; as it cuts at the taproot of the social justice core of the Indian system of law and governance. It is also to be marked that this was done first in Kerala, even three months before the Hindu Nationalist party made it at the centre.

In Kerala, the Brahmanical forces who began their outcries against social justice and community reservations from 1957 onwards through Joseph Commission, pushed it through the left and eventually succeeded in the “creamy layer” claim and the economic category was pushed into the social justice ethical paradigm to gradually supersede and replace it surreptitiously. It was done in Devaswom Board that was almost 90 percent filled with a particular caste Hindu social group and is a clear violation of facts, statistics, reality, history and justice related to social inclustion and representation.

What the RSS feared to say aloud was carried out through the Left by the Brahmanical and its militant Sudra subservient forces who were doing the litigation for it in Supreme Court for almost fifty years now. They did the Sanskritic epic recitals and reiterations in Malayalam that was critiqued by Kerala cultural historians like Ilamkulam in the 1950s as “Mavarata Pattatanams”.

The monopoly forces who are already over represented in various realms of the state are further grabbing power by diluting and subverting the social justice paradigm of the constitution by pushing the ahistoric and anti-constitutional economic criterion that is clearly against the social justice thrust and ethical core of our constitution. Film folks must also realize the fact that the basic freedom of expression that makes art, culture or cinema possible is enshrined in our constitution. Otherwise like the Palestinian director Elia Suleiman how many of us could make films in exile?

This is the context in which an untouchable woman fighting for justice for her son who was brutally murdered by police in custody gains significance in Mai Ghat. The washer woman is cleaning the whole fabric of the justice and law enforcement system by engaging in a decade old legal battle. It reminds us of the film Court by Chaitanya Tamhane and Shaji Karun’s film Piravi that are also greater human and filmic critiques of the Indian system of law facing many challenges in the totalitarian present. When films on social inequality are increasingly kept away from Indian festival circuit, films like Mai Ghat are worth watching, reflecting and discussing.

Films like Axone by Nicholas Kharkongor and Aani Maani by Fahim Irshad have also tried to depict the question of the exclusionary discourse of the other and hate that are consuming the kitchens and wardrobes of our homes especially in the national capital and in the cow belt. The basic livelihood issues and human rights including right to life and food or clothes are also taken up by young and woke film makers.

Let us hope that we survive the traumas and tests of this genocidal moment that is a construct of our collective and lethargic amnesia and erasures done in the context of cultural elitism, caste Hindu hegemony and the increasing Hinduization of the Sudra and Bahujans and the Brahmanization of even some affluent minority sections.

The social reality of caste inequality and historical material facts must be acknowledged by the people and their ruling elites. It must be realized that we cannot make a democratic and just nation or society on the heap of cow dung and the Smruti Sruti Purnanas. Neither the Vedic Purusha Sukta nor Gita or Manusmruti would help us to prevent an Indian holocaust.

The real history and social realities of people are vitally important. The modern democratic values enshrined in the preamble of the constitution are key. Unless and until we recognize the reality of our past and the real legacies of ethics and enlightenment in a deeply engaging and compassionate way our journeys would lead to the camp. Today me, tomorrow it is you. And cinema or any cultural art form also contributes immensely in this collective amnesia and evasion of reality. It can also contribute greatly in resisting this amnesia and realizing the real legacies and lasting values of humanity and an ethical way of life deeply embedded in our soil.