Professor Jayendran, who spent a lifetime teaching English to generations of young scholars in a celebrated college in Kozhikode, lives in a modest home in the city outskirts. A chronic bachelor, he spends his time reading and writing, and is happy to welcome visitors. He makes it a point to show visitors a simple bedstead that occupies the pride of place in his bedroom, a prized possession he has inherited from his illustrious ancestors who lived in the old colonial town of Thalassery. “Sree Narayana Guru slept on this bed when he was our honoured guest almost a century ago,” he tells his visitors.

That visit to his ancestors’ home took place during the early years of the 20th century, when the Guru travelled to Malabar as part of his social reform initiatives. The few occasions he was in Malabar, he met community leaders, intellectuals, businessmen and professionals and urged them to eschew retrograde practices like animal sacrifice and child marriage widespread in the community, and encouraged them to adopt modern educational and social practices that were suited to a community’s progress. He established a few temples and ashrams during those visits, in places like Calicut, Thalassery, and Kannur, and some other places.

Among the temples that the Guru had established in Malabar were the famous Sreekanteswaram temple in Calicut (1910), the Jagannath temple in Thalassery (1908), and the Sundareswaram temple at Talap in Kannur (1916). During those visits he came into contact with a large number of the Thiyya community leaders.

Among the people who came to receive the Guru and organize various programs on his behalf were eminent community leaders like C Krishnan, a famous lawyer and editor of Mitavadi, and Kallingal Madathil Rarichan Mooppan, an important landlord, in Calicut; Moorkoth Kumaran, writer and scholar, Vayaleri Kunhikkannan Gurukkal, later known as Vagbhatananda Guru, in Thalassery; and Oyitty Krishnan, Kottiyath Ramunni, Choyi Butler, Munsiff C V Gopalan, and many others in Kannur and other places.

They belonged to prominent families whose fortunes were mainly made from contacts they had built up with the Europeans. For instance, Choyi Butler, used to run a famous seaside hotel called Choyi’s Hotel in Kannur beach, a favourite haunt for European visitors in the pre-independence days. This legendary businessman was the first president of the committee set up for establishing the Sundareswaram temple at Kannur under the guidance of Guru during the First World War years, when many young men from these families had joined the British army and had served at war fronts across the three continents of Europe, Africa and Asia.

In a recent book, A Hundred Years of Excellence, on the history of the family, one his descendants writes: “Sri Choyi was the uncrowned king of Cannanore, the grand old man who ruled over a mammoth family…They stayed with him in Kottiyeth House, a large nalukettu building situated in a heavily wooded compound …They say Sri Choyi owned all the land from Payyambalam beach to Kanathur Kavu…The Choyi’s Hotel was built by him in one of the most idyllic sites in Cannanore, atop a hill overlooking the ocean.”

Many of the young men who served in the war brought back exotic tales of life in the other continents and of heroic incidents in the battles in such distant lands. Dr Govindan, another member of the Choyi clan, who had served in the British army is also mentioned in the book:

“Dr O Govindan who hailed from the illustrious Poothatta family was a decorated doctor in the British army and fought for the British as far back in history as the North West Frotiner wars…Dr Govindan was sent home to India from Burma after he was shot in the leg in battle, and was incapacitated from active war front duties. This story is that he fell very ill on board the ship, and one time they even contemplated giving him a burial at sea. But at the last moment he sat up in bed and proclaimed the sea could wait. He came back to Cannanore, was proclaimed a war hero and lived to a ripe old age, and died full of honours.”

However, despite their prosperity and social contacts, these gentlemen from the Thiyya community remained “untouchables,” as they were part of the lower castes in the Hindu hierarchy. A large number of Thiyyas had built up considerable fortunes in places like Calicut, Mahe, Thalassery and Kannur—all major colonial towns under the British or French rule. What helped them gain access to such fortunes was their proximity to the British/French colonial administrations and members of the European community. Many of them had received English and/or French education and also managed to possess lucrative positions in these administrations. There were many judges, revenue officers, lawyers, businessman and other professionals in their ranks, though the community remained “polluted” in the eyes of the higher castes and were not allowed entry into the upper caste temples.

It was in these circumstances that some of the community leaders got together and made plans to establish temples of their own. The result was the establishment of a number of new places of worship under the auspices of Sree Narayana Guru in the early decades of the 20th century.

In their relations with the western colonial powers, the Thiyya community played two crucial roles for European administrations. From the beginning, members of the community were the principal contractors who catered to the needs of European powers in building roads and bridges in this remote and inaccessible region and also provided food and beverages—quite essential for the survival of European military personnel in their camps located at inhospitable locales.

The second aspect was more personal: Most of the young servants of the English and French East India Companies in these parts were not able to find European brides for themselves and hence they resorted to liaisons with the local communities. They could mostly find women for such companionship among the Thiyya community in north Malabar, where the community followed matrilineal system which had enabled their women substantial independence to manage their own affairs. This helped their children achieve better prospects in life.

For instance, eminent plant scientist Janaki Ammal, who came from a Thiyya family in Thalassery, had an Irish grandfather on the mother’s side who helped the children of his local consort gain better education and social mobility. Edward Brennen, who established a high school for local youngsters at Thalassery in mid-19th century, which later became the famous Brennen’s College, had a daughter by his Thiyya consort. He had spent quite a substantial amount of money for the education of the girl, Flora, who died young in Ooty.

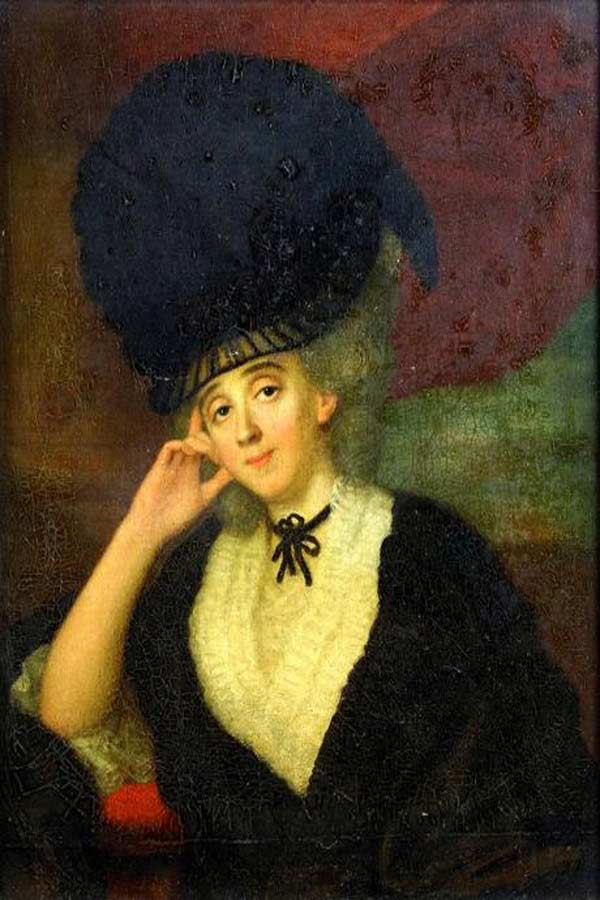

This is a practice that seems to have been pervasive from the early days of European settlements in the region. For example, in letters written from the Tellicherry fort during 1768-69, Elizabeth Draper, wife of Daniel Draper who was the officer in charge at the fort, makes frequent references to contacts with local communities and their social customs.

Elizabeth Draper was an unusual person: She was born in the Travancore fort of Anjengo to British parents, was educated in England, married Daniel Draper of the English East India Company service at a very young age and then went back to England to take care of her own children’s education where she became very close to English novelist Laurence Sterne (1713-1768). By the time she returned to her husband in Bombay, the relationship had become a matter of great scandal in English literary circles. Some of the passionate letters the celebrated novelist and the attractive socialite had exchanged have been published as “Yorick’s letters to Eliza.”

Eliza was a wonderful letter-writer and she often described the people, politics and customs of the land where she had arrived. Those were the years Hyderali had conquered much of Malabar and Mysore forces were expected to attack the English fort at any time. In one of the letters from Tellicherry, she writes:

“They are divided into five castes: Brahmins are the first, from which kings and priests come; next are the Nairs, great officers and principal soldiers; then Tivies [Thiyyas] who bear arms or served as distinguished servants; next Mukwars, fishermen and porters; finally Footiers, the lowest of all. Untouchables, they lived in villages distant from other castes because a Nair, or any other high men, were permitted to cut them to pieces if they were seen on the same road.”

Eliza describes Thiyyas as a community bearing arms, though it was mainly the Nairs who had the privilege of carrying arms with them, according to Hindu social customs. But there were a number of Thiyya families known for martial skills and many families were known as gurukkals with Kalarippayattu traditions in the northern parts of Malabar. It is also a known fact that these families were well-versed in Ayurveda and Sanskrit texts and were practitioners of the traditional healing systems.

But the feudal social customs were oppressive, and it took much effort to break the social taboos imposed by the rigid caste system on the lower-caste communities. The social ostracism was pervasive and the Thiyya community had to bear much of the brunt. The story of Ooracherry Gurukkals, a Thiyya family of Sanskrit scholars from Kaviyoor village near Thalassery, illustrates this point.

Prof. Jayendran, who has prepared a genealogy of the Ooracherry family with details on 12 generations starting from Kunhikannan Gurunathan (1764-1841) describes how his illustrious ancestor could gain access to Sanskrit learning as a child. Kunhikkannan was a Thiyya boy who spent his time taking care of the cattle of Mudoor Nambiar, a feudal chieftain of the village, and his other responsibility was to accompany the Nambiar kids to the patashala where they learnt Sanskrit texts and other sastras.

The lower caste boy who had no entry to the classroom spent time listening to the teacher from outside and diligently learnt whatever was being taught there. The boy’s effort at educating himself caught the attention of the upper-caste teacher who then got permission from village elders to allow the boy to sit in the class, along with his younger brothers. They were five brothers who later set up their own school for lower-caste youngsters, and were known as Ooracherry Gurukkal. The eldest guru, Kunhikannan, later became close to Rev Hermann Gundert (1814-1893) as his local guide and teacher, during the years when the German missionary lived in Thalassery.

A century of social reforms and upward mobility of a substantial section of Thiyya community has helped reduce its backwardness, compared to other communities in the state. In fact, in recent years there has been a debate about their relations with Ezhavas in the south. There is the widespread feeling that Thiyyas and Billavas, both northern communities, who are bracketed along with Ezhavas in matters of reservation benefits, had lost out thanks to manipulations in the system. Though there are no studies on the subject, circumstantial and anecdotal evidence points to possible manipulation of the system to the detriment of northern communities.

Take for example the recent news reports about the way Kerala Public Service Commission (PSC) examinations for police constables were manipulated by a group of Communist Party of India (Marxist) student activists in Thiruvananthapuram, a matter proved in a vigilance inquiry conducted by the PSC itself. These aspirants got themselves registered from Kasargod, a northern district where they had no connections, but wrote the examinations at the state capital and got themselves placed in the top ranks with assistance from vested interests.

This does not seem to be a stray incident and many community leaders have pointed out that such manipulations have been going on for decades, depriving the northerners of thousands of government jobs. Recently the Malabar Thiyya Sabha came out with a demand that Thiyyas should be considered a separate community in reservation matters and should not be bracketed along with Ezhavas.

However, this is not merely an issue of reservations. A deeper search for a distinct and separate identity for the Thiyya community has been gaining ground in recent years. One reason is that despite some efforts by Sree Narayana Guru and his disciples, no real integration could take place between the northern and southern communities.

While the Sree Narayana movement influenced the community at every level in the south, it could not take roots in the north. The movement remained essentially an elite phenomenon, based in urban areas. That left a huge vacuum of leadership in the lower echelons of the community, later filled by the Communist Party in the 1940s and 50s, a hold they maintained for the next half a century.

This has had wider ramifications at the social level. First, the Communist Party was totally influenced by the Soviet model of society under Joseph Stalin when Lysenko and Zhdanov were the pioneers of the doctrine of genetic and social engineering. The Thiyyas of Malabar, who came totally under the sway of the party, fell victim to this unique experiment in social engineering.

The result was that the widespread spiritual and intellectual awakening that shook most other backward communities elsewhere in the country never reached them. Their temples and other places of spiritual communion like traditional kavus were tightly controlled by the party machinery. It was an invasion of materialist politics into a realm of spirituality, a dichotomy which has had disastrous consequences.

The comparative aridity of spiritual discourses in the community took place at a time of wider social awakening on a pan-Indian Hindu identity, a phenomenon in which the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Sangh Parivar were taking a leading role. In course of time, the materialist ideology imposed on a deeply spiritual and ancestor-worshipping community failed to withstand this spiritual, or rather pseudo-spiritual, uprising in its midst. One example of the percolation of Hindutva ideology into the community is the massive acceptance of Balagokulam-sponsored shobha yatras on Ashtami Rohini day in most parts of Malabar.

The takeover of the community’s spiritual realms by the Communist Party bereft of ideas of spirituality could be seen in the way the Thiyya cultural ethos got completely ritualised, even as independent spiritual inquiries were discouraged. Ritualistic celebrations were promoted, ritual-specific functions like Theyyam and Thira were organised with fanfare, but discourses on spiritual matters gave way to more political expressions or cultural events of a ‘secular’ nature.

It is not surprising that a spiritual visionary like Vagbhatananda, whose philosophy focused on the toilers and their experiences, never got much attention in Malabar. On the other hand, Hindutva ideologues were able to promote a successful popular campaign for Ramayana, inculcating a new tradition of Ram in the warrior image.

Now, after many decades of ‘secularization’ of the spiritual sphere in the community, there seems to be a backlash. A telling indication is the severe public response to the Sabarimala issue in recent elections. The State government’s approach to the issue came in for criticism, and the erosion of votes even in the bastions of Left parties in recent elections proved the point. But this should not be seen as an isolated issue, a stray incident that would not have a long lasting impact.

The decisiveness with which the electorate showed its bitterness, especially in the old Communist bastions in Malabar, is to be seen in the light of a deeper churning in the community, groping for a new identity for itself.These days, the search for a new, distinct identity for the community is underway. Firstly, it rejects the colonial argument that Thiyyas and Ezhavas came from the island of Sinhala, and were integral to each other, forming a single community of tree-climbers across the Malabar Coast.

William Logan, who is primarily responsible for this theory, says in the Malabar Manual that the “caste now known as thiyar or iluvar were entrusted with the duty of planting up wastelands….” He argues that two of the specific privileges of the community as per Hindu traditions were “footrope right and the ladder right” (for tree climbing purposes). He says that “this character they still to a very large extent retain, as they hold to the present day a practical monopoly of tree climbing and toddy drawing from palm trees.”

This description of the social characteristics of the Thiyya and Ezhava communities were largely accepted without question by most modern Kerala historians, who were, with very few exceptions, people from the elite social classes. However, new intellectual and academic initiatives from within the community now question this theory by Logan, who was a collector of Malabar in the colonial administration.

For example, two books on the origins of Thiyyas question this southern island origin of the community and argue that they came from other parts of the world, using land routes from the north for their migration. In his 1999 book, Influx: Crete to Kerala, M M Anand Ram argues that the community has Minoan origins as they escaped from some natural disasters in the Cretan island in the Aegean sea and crossed the thin wedge of Africa in the north, which later became the Suez Canal, to reach Malabar where they settled down.

While Anand Ram employs linguistic evidence to drive home his theory, Dr N C Shyamalan, father of Hollywood director Manoj Night Syamalan, a medical doctor who settled down in the United States, argues that Thiyyas came from Central Asian regions like the present-day Kyrgyzstan through north-western land routes to reach Malabar. A member of a prominent Thiyya family in Mahe, he has based his arguments on DNA mapping of his own and other family members’ blood samples. He has a chapter in his book, North Africa to North Malabar: An Ancestral Journey (2014), which rejects the arguments of William Logan on the origins of the community, citing historical and archeological evidence.

Similar efforts were also made in the early days of social awakening in the 20th century to provide a historical foundation for an independent Thiyya identity. One of the major efforts was a book, Kerala Charithra Niroopanam by K T Anandan Master, published in Kannur in 1935. He argued the Thiyyas were a community with a superior status equal even to Namboothiris, and their social degradations were owing to the integration into the caste hierarchy of the Hindu community over a long period of history.

These might be intellectual and academic speculations, but what these exercises indicate is an urge in the community to find a place for itself, away from the shadows of Ezhava dominance and the machinations of colonial and upper-caste historians who have cast a spell on their identity and destiny for a long time.

Cover Image: Prof Jayendran