This Bakrid, the people of Wayanad had a guest among them, whose own life and destiny appears to be inextricably interwoven with theirs in an unusual way. For one, Rahul Gandhi, being the scion of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty that overshadowed the destiny of India for much of the seven decades after its independence, was never expected to run for parliament from this remote tip of the vast Indian subcontinent.

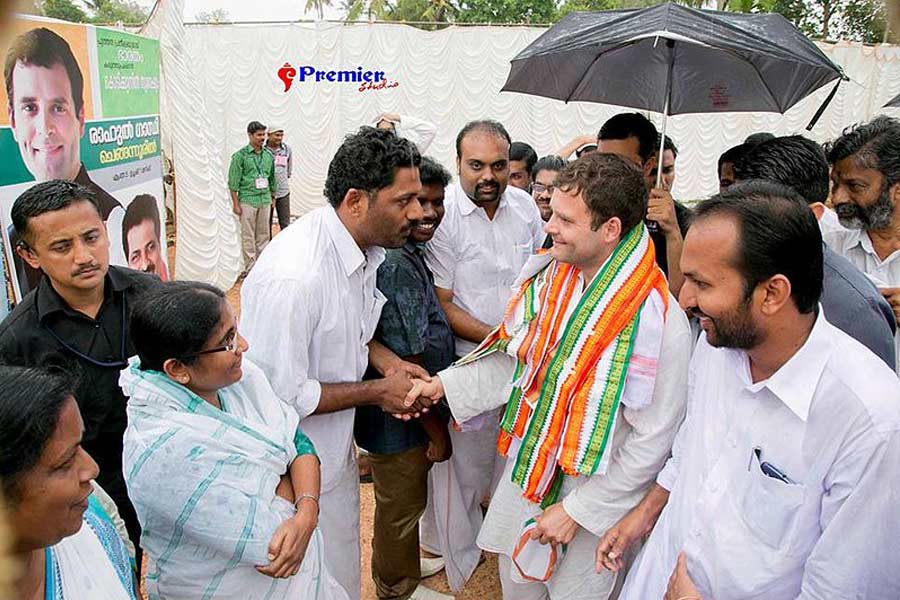

Though Rahul Gandhi was rejected by his family’s traditional pocket borough of Amethi, Wayanad wholeheartedly accepted him, offering the greatest of winning margins ever enjoyed by any candidate in the Lok Sabha elections in the state. This week’s visit to Wayanad is the second one for Gandhi after the May elections, preceded by a brief thanksgiving tour immediately after his victory.

But this time, the circumstances have changed, and Gandhi returns to a people who are desperately fighting a battle for survival. Wayanad has been totally devastated—the floods and natural disasters that hit the state for the second year running, has hit Rahul Gandhi’s constituency the hardest. Whole villages have been wiped out and thousands of people have been rendered homeless.

A human tragedy is unfolding in Wayanad, with dozens of people still buried under the debris after massive landslides bore down mightily on human habitations of Kavalappara, near Nilambur and Puthumala, near Meppadi, where the total deaths could cross a hundred, according to local people. Gandhi visited the sites of destruction and disaster during his two-day visit and comforted people who had taken refuge in the relief centers in various parts of the Wayanad constituency. There are thousands of people in the relief camps, most of them having lost almost everything they had made in their lifetime.

What does Rahul Gandhi have to offer these people who have given him the best of victory only a few months ago? He must have been struck by the magnitude of human tragedy that he witnessed for he offered words of consolation that came from the depths of his heart.

What should Rahul Gandhi do to keep his relationship with the people of Wayanad to survive the best of times and the worst of times in the lives of both? Gandhi as well as his party needs to think deeply about this one, if they are to retain and build upon the momentum gained by the bonhomie and the great expectations that arise out of this moment. I think there are possibilities for Gandhi to start a fresh and original relationship here in Wayanad, something unique and original in our national politics that perhaps one day, his own experiments in Wayanad could prove to be a model for parliamentarians across the country.

Right now, Gandhi appears to have struck a chord in the hearts of the people he represents, and with the right effort and a clear plan of action, he can build upon it as a model for public action and public representation in the country. This is an important moment, because the relationship between the leader and the people is rather tenuous and could break up never to mend again, as has happened to Rahul and the Gandhi clan in their traditional home grounds in Uttar Pradesh.

For such a new experiment to come to fruition, we will have to go back in history when our greatest leaders involved themselves in public life in a country weighed down under the yoke of colonial domination. Mahatma Gandhi’s own life is an example—how a young lawyer in South Africa who went there on a temporary assignment, turned out to be a leader whose life and work remains a legend even today. The point about Mahatma’s experiments in public life is that he responded to the challenges that were presented to him and never wavered from his chosen path. Power, prestige, money or fame could not influence him in his life and work.

Rahul Gandhi has shown willingness and resolve to take risks and trudge the lonely furrow. His resignation as Congress President and his unwillingness to change his mind despite months of pressure from the Working Committee (CWC) says something about the character of the man. Perhaps, his real qualities of leadership will emerge in the coming days when he fights the toughest political battles against a powerful establishment of Hindutva forces, who had singled him out as their greatest enemy, and continue to do so despite his resignation as party leader.

So, for Rahul Gandhi, a long term strategy is called for, and perhaps what he encountered in Wayanad in these worst days of his and the people’s lives could prove to be the trigger for a life in public service worth his own illustrious predecessors. But what could be the contours of such a strategy?

That is a matter still steeped in the vagueness of contemporary politics and experiences, but what is evident is that the new experiments should eschew what is expedient and what is of short term gains in public life. If Gandhi is to begin a new experiment in Indian public life as a practical and abiding response to the Hindutva challenge in the country, he would have to begin at the beginning.

What does it entail? It means taking the efforts to build bridges between people of all faiths, all social classes, who have managed to remain a great collective despite the cynical efforts to divide them in the past. Wayanad is the place to begin such an experiment, as all the major communities live here with a tradition of social cohesion and amity.

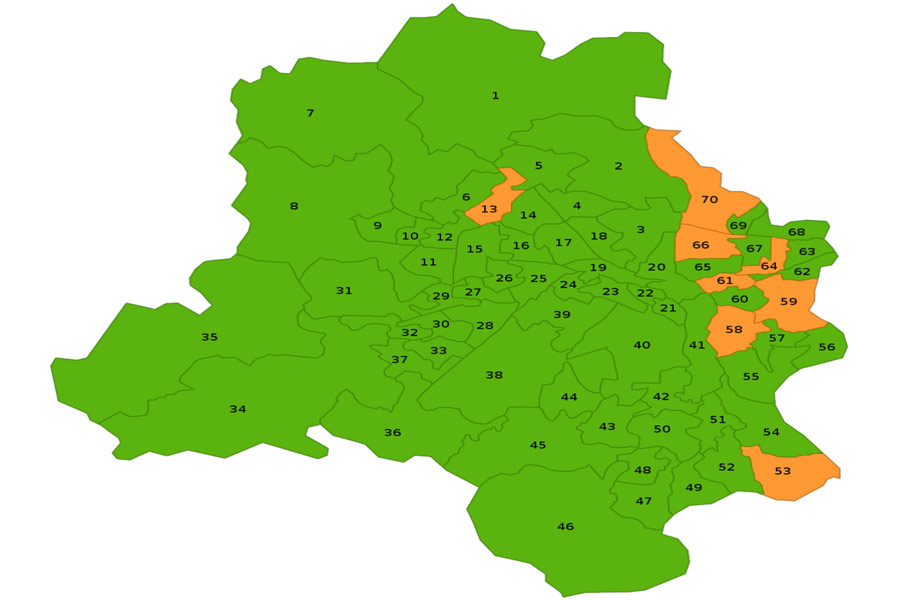

When Rahul Gandhi came to Wayanad, the Sangh Parivar politicians had played their familiar trick of dubbing it as a Muslim-majority constituency despite the fact that all three major communities have excellent representation in the various segments of this constituency. So what should be the beginning of his new experiment ought to be a social and community camaraderie that shines as a model for the entire country.

Secondly, Wayanad is a place that represents the worst experiences of globalization practices that has rode roughshod over the common people and peasantry. Its farm produces and cash crops have faced the worst impact of the price fluctuations in the global market, driving hundreds of people in many villages to suicide in the past decades. So, economic regeneration and cooperative efforts to help people gain a meaningful livelihood with their meagre resources is an important step.

How to develop alternative economic models in these graveyards of free market policies in Indian village society is a big challenge. Hopefully, with the national and global expertise he commands, Gandhi could make a new start in Wayanad for a regeneration process.

Thirdly, Wayanad epitomizes the tragedies of global warming today. Its climate is taking a definite turn for the worse, as it was predicted long ago. Its villages are now being deserted; the man-animal conflict is a terrible reality in many villages bordering forests. Perhaps, tourism could bring in new sources of income—but here again, all stakeholders including the villages and the animal population should have their interests protected.

So for Rahul Gandhi and Wayanad, this is the occasion for a new beginning, a new experiment in building a constituency that should offer an alternative model for the entire country. The basic steps for the process are building trust among the people, building better bridges among the people, communities and all living entities that clamor for a space in its environs.

For a start, Gandhi could rent out a house and live with the people of Wayanad for a few days every month, and share their pain as they build their lives back.

Cover Pic: Representational Image; Wikimedia Commons