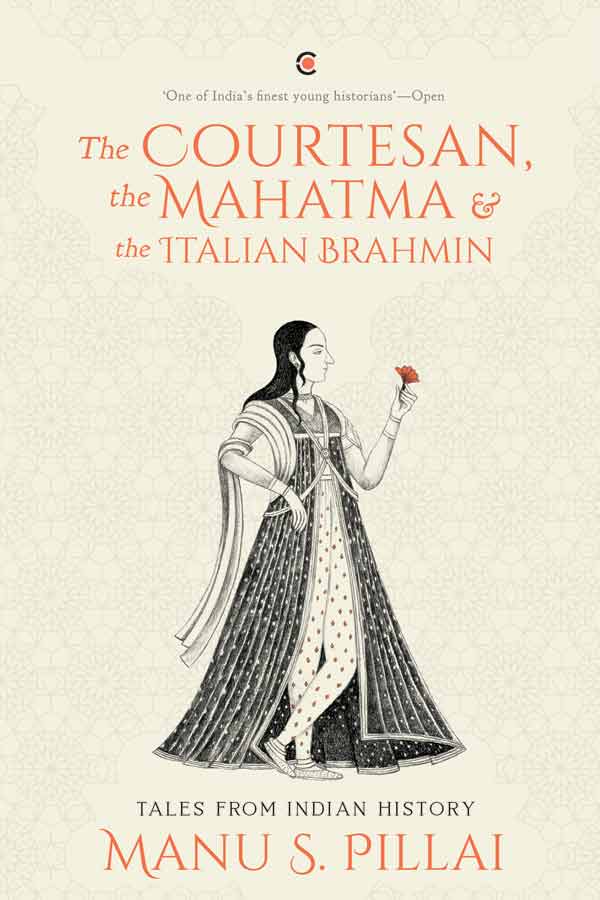

The Courtesan, the Mahatma & the Italian Brahmin by Manu S Pillai is a rich tapestry of historical essays, myths and legends that have escaped the attention of historians—perhaps because of their ordinariness or, as is often the case with history, the nuanced characters not being on the winning side of the narrative. But the protagonists are anything but ordinary. The 60-odd essays delight us at every turn of the page as they speak of extraordinary lives that shaped the destiny of modern India with all its paradoxes.

Divided into three parts—Before the Raj, Stories from the Raj and an afterword, the book has been carefully curated from the author’s own columns in the Mint Lounge and other publications. You encounter an eclectic potpourri of characters—from an Italian Brahmin to the three-breasted deity Meenakshi, the warrior Princess; a Muslim deity in a Hindu temple; the Courtesan who became a princess; and others, blurring lines between myths, legends and facts that persisted in medieval India.

These stories are vital, not just enabling us to see glimpses of a past that have eluded us, but also to understand how we have emerged as a nation, caught between religious, caste and gender conflicts. As the author himself reiterates in the introduction:

We live in times when history is polarizing. It has become to some an instrument of vengeance, for grievances imagined or real. Others remind us to draw wisdom from the past, not fury and rage, seeing in its chronicles a mosaic of experience to nourish our minds and recall, without veneration, the confident glories of our ancestors. The collection tells stories from India’s countless yesterdays and of several of its men and women. It is an offering that seeks to reflect the fascinating, layered, splendidly complex universe that is Indian history at a time when life itself is projected in tedious shades of black and white. There is much in our past to enrich us, and a great deal that can explain who we are and what choices must be made as we confront grave crossroads in our own times.

Pillai weaves magic with words and details of another time and place, transporting the reader to a not so distant past where diverse religions co-existed with shared cultural traditions—where Sultans and Maharajas reigned with compassion and sense of justice; where women warriors were worshiped, and matrilineal societies flourished.

Fraught with intriguing details, Pillai draws out each character with engaging wit, caricature and empathy. There are moments when one wonders if all this was one big cirque du soleil entrapped in linear time. Exquisite illustrations by Priya Kuriyan only added to the brilliant palette of historical nuance.

What stands out is the labour of love that has gone into recreating stories to showcase the diversity of a forgotten medieval India. The Courtesan, the Mahatma and the Italian Brahmin, in most parts, is a tribute to powerful women like JodhaBhai or Marian Uz Zaman, who was more than Akbar’s wife and held a military rank; Muddupalani, the feminist erotic poet who fought patriarchy and Victorian morality that tried to deride her eloquent 584 poem epic Radhika Santwanama; Mahabharatha’s Shakunthala, as opposed to Kalidas’s more docile one; the bibis of Arakkal and the immensely talented and beautiful Princess Meerabai, who gave up everything for divine love to become the Poet-Saint.

The most magnificent and daring of all undoubtedly is Nangeli, the woman who valiantly took on the caste system in Kerala by cutting off her breasts, protesting the Breast Tax that was prevalent in Kerala in the 19th century. Pillai thus becomes the ultimate feminist historian stringing together such touching narratives, bringing glory to those women, whose contributions have been largely ignored by the book of time.

What stays with you, long after the read, is this sense of nostalgia for a past that was far more vibrant and inclusive, where Muslim and Hindu kings, though at loggerheads for kingdoms and annexations through the ages, were patrons of arts, languages and inclusive cultures. They loved their subjects dearly irrespective of caste or religion. You had Mughal Kings with Rajput wives and Hindu kings marrying Persian princesses; Sanskrit was one of the official languages in the Mughal court and Persian among the official languages in the Maratha court. As Pillai states:

There is among certain sections of people even today a quest to find the true essence or the purest version of the past. The irony is that such a past does not exist, and what exists is not pure but layered and marvelously complex. A past where there are Hindu Sultans and Maratha Padshahs, where the forebears of a Hindu King could seek the blessings of a Muslim Pir.

The author goes into a parallel world scenario in Part 2—Stories from the Raj—contemplating possible historical outcomes: “What if there was no British Raj” or “What if Mahatma had lived”, giving us glimpses into the British Empire with unforgettable characters and their engagement with India—Kings and queens, rebels and reformers, who stood by the Empire, and others, who fought against them. There are interesting accounts of Rowdy Bob of Plassey, Queen Victoria’s love for India, the Arakkal Queen of Lakshwadeep and the forgotten Queen in Paris—the last queen of Awadh.

Pillai gives us further insight into our own troubled and often violent past, the reasons for much of our ills today—from Savarkar’s thwarted racial dream to the events leading up to the Ayodhya Temple dispute. The future of India is a bleak one if hyper nationalism and Hindutva plays a pivotal role in the social construct, as the author surmises in a melancholic tone:

If the Mahatma had lived a full life, as he once desired, the obituary on his death would have sadly said, “Mr Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, one-time barrister of law, one-time freedom fighter, and neglected thinker of an orphaned philosophy, passed away yesterday. He was 125 years old and died of a shattered heart, in a country he is no longer recognized.”

The Courtesan, the Mahatma & the Italian Brahmin in a surreal sense gives you reason to hope, to dream, to question and fight for the idea of India—that a syncretic India is not just possible, it is just a heartbeat away. The ghosts of our pasts stand testimony to this.