In recent years, Indian science has been experiencing a transformation that can only be described in terms of magical realism—with the ruling politicians as well as policymakers in the field of science and education extolling the virtues of going back to the ancients. There is nothing wrong in taking legitimate pride in the past and its glories, which most societies with ancient civilizational roots are prone to do, but in India’s case, such tall claims from the top-notch establishment has reached a level of ridiculousness that made it a laughing stock across the world.

The sense of loss and shame felt by the scientific community in India is palpable, and the long-term impact of these delusional claims that are seen disturbingly percolating to school textbooks and even into the sessions of the Indian Science Congress are raising concerns about India’s future as a world power with firm foundations in science, technology and rational ideas.

Gone are the days when India made real efforts to forge ahead in the fields of scientific enquiry and research, despite the odds it faced as a fledgling democracy with meagre resources. It is in these gloomy circumstances that E K Janaki Ammal (1897-1984), one of the pioneering Indian scientists of the 20th century, returns to limelight decades after her death in 1984 at the age of 87. The nomenclature of a newly-developed rose variety after the great botanist and cytogeneticist was received with much acclaim in recent days.

The last time people of Kerala heard about Janaki Ammal was during the Silent Valley agitation in the mid-seventies, when the globally-renowned veteran scientist came out to protest strongly against the move to deluge the biodiversity hotspot under a sheet of water, to generate hydel power for Kerala. The project for a new hydel power station at Silent Valley was mooted by the C Achutha Menon government (1969-1977), and it had the support of all trade unions and major political parties across the political spectrum. The opposition came from a fledgling people’s science movement, represented by the newly-formed Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad (KSSP), and some individuals with scientific temper and environmental awareness tuned into the ecological concerns raised in the western academic circles.

Janaki Ammal was a pioneer of this global environmental movement, as she was a delegate to the 1955 Chicago conference to deliberate on the “impact of man’s activities on the physical-biological environment of planet earth”. It was one of the first academic conferences ever on the subject and she was one of the two Indians present there, the other being Radhakamal Mukerjee, eminent social scientist. At the time Janaki Ammal was in charge of the Botanical Survey of India (BSI), headquartered at Lucknow. She had returned to India in 1952, at the invitation of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, after many years of work at the John Innes Institute and the Royal Horticultural Society, UK.

The environmental concerns and an intimate knowledge about the traditional knowledge systems passed on through generations of indigenous communities has been a part of the intellectual heritage of Janaki Ammal, who grew up in a traditional Thiyya family of vaidyas, in Tellicherry, in the old British Malabar on the west coast of India. As a field researcher on plant species and as a botanist, she was passionate about India’s rich biodiversity and went on collection drives from Wayanad in the Western Ghats to the hills of Shillong and the valleys of Kashmir and even to those inaccessible forests of central India. This passion never left her and in the mid-seventies, when she lost hope that the Silent Valley could be saved, she decided upon a bold plan to salvage whatever she could, before it was inundated.

In a letter to her lifelong academic partner and mentor C D Darlington, she wrote: “My dear Cyril, I am about to start a daring feat. I have made up my mind to take a chromosome survey of the forest trees of the Silent Valley which is about to be made into a lake by letting in the waters of the river Kunthi.” She was 80 at the time, and in semi-retirement at the Maduravoyal research station of Madras University’s Centre for Advanced Studies in Botany, where she served as scientist emeritus those days.

She seems to have inherited this passion for knowledge and love of nature from her ancestors, on both sides of her parentage. She was the daughter of Dewan Bahadur E K Krishnan, a sub-judge in the British judicial service at Tellicherry. Janaki was the tenth of a brood of 13 children his second wife, Devayani, bore him. The Krishnan household was embarrassingly rich in its offshoots, with six children born earlier to his first wife, Sarada. Devayani’s father was John Child Hannyngton, an officer of the East India Company, who served as a judge at the local sessions court from 1861 for a few years, and later as the British resident at Travancore royal court. Hannyngton, an Irishman, had an affair with a local Thiyya woman, Kunchi Kurumbi, during his ten-year sojourn in Malabar, and she bore him two girls, Devayani and Martha, who later married an Anglo-Indian young man in Madras. Krishnan married Devayani after the death of his first wife, obviously with an eye on the career prospects it could bring him in the British colonial service.

Hannyngton appeared to have taken care of the basic needs of his native-born children, and also maintained cursory contacts with his son-in-law Krishnan, in stark terms of a master and dependent. In a recent academic study, Vinita Damodaran of Sussex University, great niece of Janaki Ammal, quotes a letter Hannyngton wrote to Krishnan in March 1883. In response to the information that Krishnan was expecting a promotion in service, Hannyngton said that “I am very glad to hear that you have a good chance of promotion. You will require it if your family goes increasing at this pace”. He said he was planning to go home to England to “see after my four sons,” and “it is not unlikely I will look you up on my way to Bombay.” He asked Krishnan to tell his mother-in-law Kunchi Kurumbi that “it is no use to write to me I won’t correspond.”

Edavalath Kakkat Krishnan belonged to a family that copied the European ways in their lifestyle and upbringing of their children, though they were at the receiving end of the caste hierarchy in India. He came from a family of traditional vaidyas and scholars and his maternal grandfather, Oorachery Kunhichandan Gurukkal, was the youngest of the five brothers known as Oorachery Gurukkal based in Kaviyur village near Tellichery. The eldest of them, Kunhikkannan Gurukkal (1764-1841), was known to have been a Sanskrit and Malayalam tutor to German missionary Hermann Gundert (1814-1893) during the years he spent for missionary work in Tellicherry. The family had many vaidyas in its ranks familiar with medicinal plants and herbs, of much importance in traditional treatment systems.

Krishnan kept an excellent garden at his seaside home (called Edathil) and he was a bird watcher who wrote two books on the avian species he encountered in North Malabar. His boys were fond of playing cricket, a game that was brought to Tellicherry in late 18th century by colonial administrators and among the early players in its renowned stadium was Arthur Wellesley, later the first Duke of Wellington, the hero at Waterloo and twice prime minister of Britain.

On her mother’s side also, Janaki had relatives with similar qualities and scientific pursuits. Grandfather J C Hannyngton himself was known for his collection of rare species of plants and herbs and he had sent a few samples to the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew in UK. These were orchids of a rare nature that he had found at Western Ghats at elevations beyond 3000 ft. His son Frank Hannyngtotn, who also served in the British colonial administration, was an avid entomologist who had great collections of butterflies in Coorg, Kumaon and other places. At Chumbi Valley in Bengal, he found a new species which was named Parnassius Hannyngtoni.

Janaki must have drawn from these family traditions in her own eventual elevation as India’s topmost botanist and cytogeneticist through many decades of hard work and professional perseverance, despite having to face discriminations of caste and gender at every step. After her schooling at Tellicherry, she had moved to Madras where she graduated at the Queen Mary’s College and then received her Honours in Botany at Presidency College in 1921. While teaching at Madras Women’s Christian College (WCC), she received a scholarship for study at Michigan University, USA, where she completed her master’s degree in 1925. She was back at WCC, but soon went back to Michigan as a Barbour Fellow to do her DSc, which she obtained in 1931. In 1955, the Michigan University conferred on her an honorary doctorate, Legum Doctoris, in recognition for her great work in the next two decades.

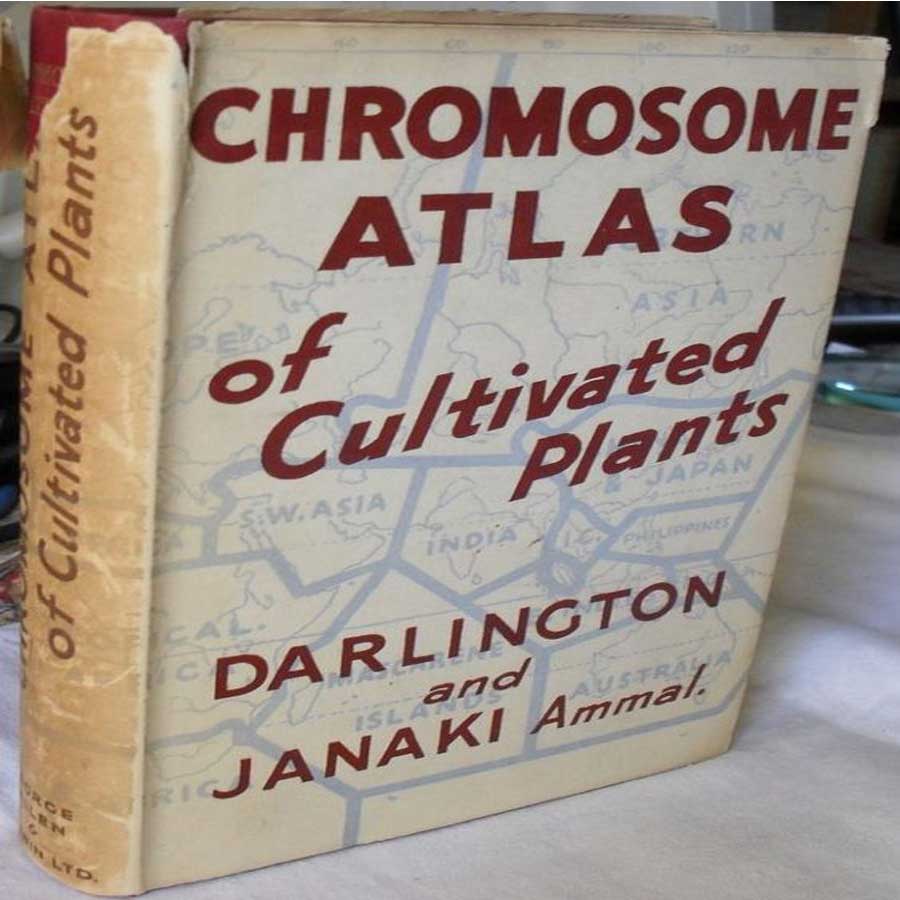

As a cytogeneticist, she soon found a place at the Imperial Sugarcane Institute at Coimbatore, a premier national institution that worked for improvement of Indian sugarcane varieties. She was successful in breeding a high-yielding hybrid variety, but was quite upset with the caste and gender discriminations she had to encounter at this institution run by upper-caste male colleagues. She was a single woman from a ‘lower’ caste and that was enough to make life hell for her those days. The paternalism practiced by her senior colleagues was palpable, and a research paper she had submitted for publication in an international journal was held back deliberately. She complained about this to Darlington, whom she had first met at John Innes Horticultural Institute in United Kingdom where she worked for a brief period on her return from Michigan in the early thirties. Later she returned to John Innes Institute in 1939 where she collaborated with Darlington on the monumental work, Chromosome Atlas of Cultivated Plants.

Her return to the UK after an unhappy but highly-productive stint at Coimbatore came under unusual circumstances. The war clouds were on the horizon when she arrived in the UK for the seventh International Genetical Congress that started at Edinburgh on 23rd August 1939. However, the very next day, things started becoming too hot and many delegations began to leave. The conference itself was prematurely brought to a close on August 29 and by that time Janaki realised there was no way she could get back to India. She was offered a position at the John Innes Institute and hence started another decade of professional life in the UK, first at John Innes from 1940 to 45 and then at the Royal Horticultural Society at Wesley, until her return home in 1948.

Her return to the UK after an unhappy but highly-productive stint at Coimbatore came under unusual circumstances. The war clouds were on the horizon when she arrived in the UK for the seventh International Genetical Congress that started at Edinburgh on 23rd August 1939. However, the very next day, things started becoming too hot and many delegations began to leave. The conference itself was prematurely brought to a close on August 29 and by that time Janaki realised there was no way she could get back to India. She was offered a position at the John Innes Institute and hence started another decade of professional life in the UK, first at John Innes from 1940 to 45 and then at the Royal Horticultural Society at Wesley, until her return home in 1948.

She met Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru on the flight back home and on his invitation, decided to take up new responsibilities in the newly-independent country. Nehru was building India’s premier institutions of research and education and was actively searching for talent. She was made Director of Central Botanical Laboratory at Lucknow where her focus was on preserving India’s botanical wealth but, as usual, she had to wage many battles in the scientific establishment and with a lethargic bureaucracy.

The major disputes were about the focus of Indian scientific initiatives, with two streams of ideas contesting for dominance. One was the view that scientific and research institutions should follow the government’s policy perspectives with an eye on nation-building. The other was to maintain independence of such institutions as they were mainly meant for knowledge generation. The former view got the upper hand and soon, policies were formulated to jump-start growth and find ways to reduce poverty and related problems.

Food shortage was a serious concern and vast tracts of forest lands were converted into farm lands, destroying immense biological wealth across the country. Janaki Ammal once lamented that she went 37 miles from Shillong in search of the only tree of magnolia griffithi in that part of Assam only to find it had been burnt down. In her 1955 paper for the Chicago Conference, she talks about the need for preserving the traditional knowledge systems that sustained humanity for ages.

After she retired from the Botanical Survey of India as Director General in 1959, she worked with the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR) to reorganise its various research centres and also guided a number of young scholars. Later, she became part of the Madras University’s Advanced Centre for Botanical Studies and spent much of her final days at its Maduravoyal station, where she died peacefully at the age of 87.

Ammal lived alone all her life except for a large brood of cats at home for company. These pets were part of her simple life right from her younger days. In a recent memorial note, scholars at the John Innes Institute remembered she had smuggled in a palm squirrel when she came to the UK for her first sojourn there in the thirties. It was called Kapok and lived there for a long time.

Janaki Ammal was a nationalist even as she straddled the global stage as a major figure in her fields of expertise. She was a Gandhian, who remained frugal in her ways and tastes. She lived a life dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge and never spoke much about herself, as her close relatives remembered. “My work will speak for myself”, she would say.

Janaki Ammal left behind an immense legacy and her life and work has been the subject of serious academic studies, including the recent papers written by her great niece Vinita Damodaran at Sussex University. Her name remains part of the botanical taxonomy, as one variety of magnolias is named after her—Magnolia Kobus Janaki Ammal. Recently, a new strain of roses have also been named after her, bringing the grand old lady of Indian science back to public memory at a time when modern science and its pursuit is seen as an inferior activity by people who rule the country of her birth.