When Mahatma Gandhi embarked on his pilgrimage to Dandi, so expectant was he of his arrest that he wrote a letter the previous night to Jawaharlal Nehru, foretelling it. The British were notorious for not living up to expectations and not only did Gandhi wake up a free man on 12 March, 1930 but also triumphantly fulfilled his endeavour on 6 April.

Consequently, with Mahatma’s morale boosted, he decided to go beyond “picking a seer or two of salt from here and there” and announced in a speech at Chharwada on 26 April to raid major salt works at Dharasana to live up to the epithet of “salt-thief”.

Before the sixty year-old could set off on the second pilgrimage, the British exhibited their notoriety again by arresting him on 5 May from his camp at Karadi. Thus, he was forced to change his destination from Dharasana to a more familiar one—Pune’s Yerwada jail, depriving him of the opportunity to mail his letter to Lord Irwin, which he had meticulously drafted on 4 May.

Furthermore, the wary British also apprehended Mahatma’s successor Abbas Tyabji, the grand old man of Gujarat on 12 May. Notably, Tyabji had previously communicated his intent to stride towards Dharasana with 300 volunteers from Karadi on 12 May and raid the salt depot on 15 May.

The former judge of Baroda High Court, Tyabji, set out from Karadi Camp on the announced date at 6 am, after Kasturba Gandhi had put the kumkum mark on his head and garlanded him.

Remarkably, the date was exactly two months from 12 March, when the Mahatma had commenced the historic March to Dandi. Singing Mahatma’s favourite bhajan, Vaishnav jan to, the party had hardly marched for a furlong when the District Magistrate, along with Superintendent of police and 400 armed policemen, greeted them.

Although earlier than expected, the meeting was cordial with Tyabji not resisting their invitation to prison. And incarcerated along with him were 57 marchers of Mahatma’s batch and activist Jugatram Dave, whose transgression was going to see Abbas Tyabji.

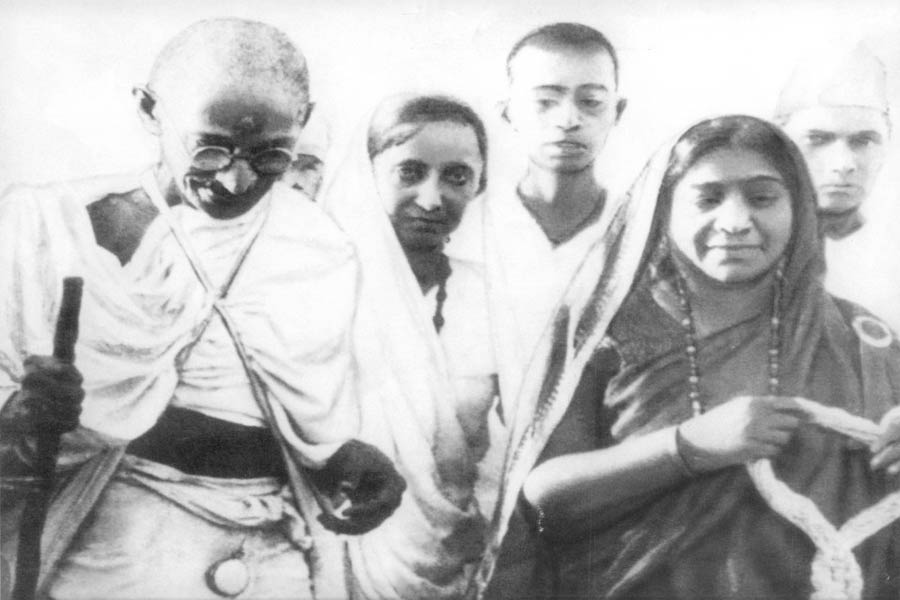

Thus, filling the leadership vacuum was the once critic, now admirer of Salt Satyagraha—Sarojini Naidu. To fulfil the promise made to the Mahatma, she arrived early morning on 15 May at the Untadi Camp directly from Allahabad, where she had gone to attend the meeting of Congress Working Committee.

After receiving the blessings of their venerated Ba, the Satyagrahis started marching towards their destination at 6:30 am. Leading them was Sarojini Naidu, whom the Mahatma had anointed as the first Indian woman President of the Indian National Congress in 1925.

Conspicuously, for an orthodox society, the Salt Satyagraha witnessed widespread participation of women. A few among them, flaunting it as a badge of honour, even courted arrests. Awarded with a nine month sentence on 14 May, Rukmini Lakshmipathi became the first one to attain this feat, followed by Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, whom the British had bestowed with a year’s imprisonment.

If women’s participation was a big step for Indian society, a woman leading the march of men was a radical leap even by Britain’s yardstick, which conceded electoral equality to women only in 1928. In a society where widows were burned alive as part of a custom, who else, but the Mahatma, could have made this radical act possible?

Nothing less than either victory or death would she accept—that was the indomitability of the poetess-turned-freedom activist. Hardly had they walked for 35 minutes when Superintendent Robinson of Surat, bolstered by reinforcements from Jalalpur, confronted them at preventive officer’s office about half a mile from the deposits along with sixty policemen.

The police, to check the advancing Satyagrahis, sprang a surprise: An imitation of Mahatma’s Satyagraha.

What unfolded was an unprecedented battle between two armies, with neither of them ready to strike or leave the battlefield. A woman in her fifties, sitting in May’s burning heat, leading a group of men was an exciting moment that many were yearning to see. After twenty-seven hours of this face-off, the police at about 10 am on 16 May declared Satyagrahis arrested and drove them back to their encampment.

Till 20 May, this stalemate continued. Finally, 21 May witnessed the most audacious event of the campaign. Significantly, on that momentous day when imitators were going to fail in their Satyagraha, Mahatma’s Satyagrahis were going to pass with flying colours.

Draped in khadi, as the Mahatma had mandated, 1570 Satyagrahis marched ahead like a white flowing river. Guiding them in their endeavour along with Sarojini Naidu were Imam Abdul Kadir Bawazeer, Narahari Parikh, Pyarelal Nayyar and Gandhi’s second son Manilal.

To raid the heaps of glistening salt, chanting the revolutionary slogan “Inquilab Zindabad”, they reached the salt works at 6:30 am. Enthused with the spirit of patriotism, ignoring the police’s warning to disperse, they advanced in columns towards their goal.

Suddenly, scores of police men rushed towards the first column and rained blows on the Satyagrahis with steel-shod lathis. Strikingly, none tried to fend off the blows. Writhing in pain, they went down like nine pins, after which, the stretcher-bearers carried off the injured for treatment.

Then, without fear of death or injury, advanced another column, only to get whacked on their unprotected skulls. This went on unceasingly. Notwithstanding what awaited them, columns after columns advanced with their heads held high.

With time, the exasperation of police grew and so did their barbarity. Angered by the non-resilience, the Police began beating the Satyagrahis coldly, savagely kicking them in the abdomen and testicles. People at a distance could distinctly hear the lathi blows.

Bleeding from the gashes on their scalps, bodies toppled over in threes and fours, stretcher-bearers carried back a stream of inert, bleeding bodies. 741 people sustained injuries that day. Though the brutality of police was blood curdling, his men bore everything unflinchingly and without retaliating, adhering to the Mahatma’s ideals.

Administering everything from a distance was Sarojini Naidu, when the words she had long been craving to hear were pronounced: “You are under arrest.”

But the movement had long passed the stage it depended on the leadership of individuals. Neither arrests of their leaders nor bleeding heads of their comrades waned the enthusiasm of the Satyagrahis. Hence the raids continued till 6 June, exactly two months from Mahatma’s breaking of the salt law at Dandi.

Incontrovertibly, this was Mahatma’s handiwork. His choosing to oppose the regressive salt tax, which affected the common people the most, linking them to this campaign. He had sensitised the common public with the true meaning of Satyagraha to forestall the recurrence of the Chauri Chaura incident.

Only because of his genius and labour did that day go into the annals of mankind as the day on which violence was defeated by non-violence. Who else, other than Mahatma, could have made it possible even without his physical presence?