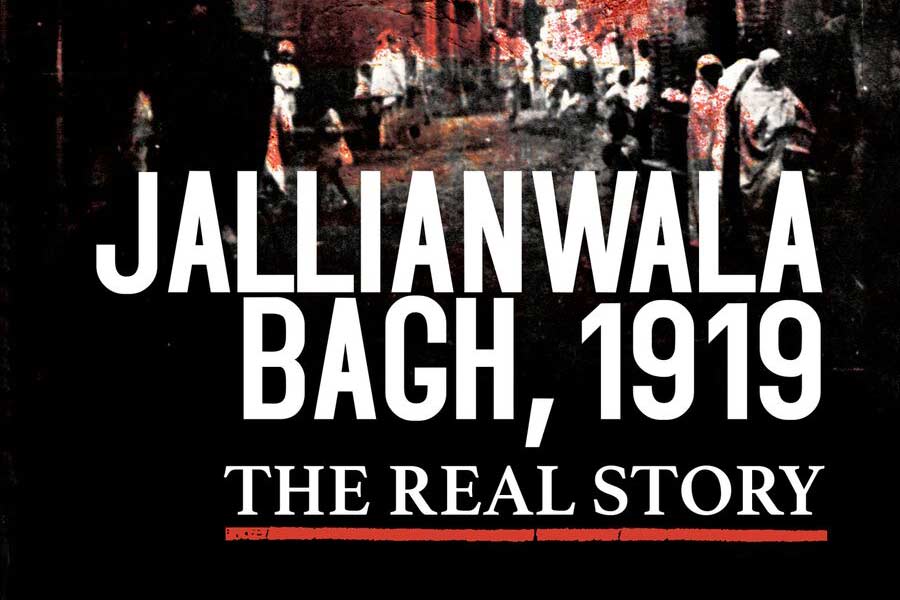

One hundred years later, the Jallianwala Bagh massacre remains the most heartbreaking episode in the history of the Indian freedom struggle. Brigadier General Dyer deliberately murdered more than one thousand fellow British subjects—all Indians, including little children—and called it a ‘merciful act’.

Not only did Dyer think the cold-blooded murders would ‘do a jolly lot of good to the people’, he even had widespread support among the British. Instead of condemning him, most of his compatriots commended him for saving the Empire as the massacre was thought essential to prevent another 1857-type mutiny. Prior to the killings at Jallianwala Bagh, there had been signs of increasing unrest in Punjab. These signs were being interpreted as sedition, even though the causes of the unrest were varied. Indeed, it is impossible to understand what happened on 13 April 1919, without an examination of the barbarism unleashed in Punjab under the regime of the then Lieutenant Governor Sir Michael O’Dwyer, to suppress the so-called rebellion. The ‘rebellion’ in retrospect was nothing more than the first signs of colonised people demanding equal rights. But it was constantly argued that Indians were incapable of self-rule and needed the British to govern them.

The scale of oppression in Punjab, and especially Amritsar, just before and after the Jallianwala Bagh killings was extreme. A deeply racist regime was in operation, no matter what kind of garb was put upon it, or the kind of defence made for it.

The murder of more than a thousand innocents at Jallianwala Bagh was not an isolated event. This was not the knee-jerk reaction of a deranged General. Dyer fired for ten minutes upon a peaceful crowd gathered to protest the Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act, 1919 (usually referred to simply as the Rowlatt Act) and continued to fire upon them even as they tried to escape. This incident was squarely a part of a systemic failure of governance during which people were exploited and mistreated. When they, tormented beyond endurance, reacted occasionally with violence, they were sadistically suppressed, their rights snatched away by the Raj.

One wonders why the true events in the Punjab of that time have been given so little prominence in popular historical literature and cinema. The commonly held narrative runs as follows: people gathered at the Bagh on 13 April 1919 for an anti-Rowlatt Act meeting; many amongst them were outsiders who had come to Amritsar for the Baisakhi festival. Dyer decided they had broken the law, gathered his troops and fired upon them. Hundreds died during the firing, and many jumped into a well at the Bagh while trying to escape the bullets. The dead included women and children.

One wonders why the true events in the Punjab of that time have been given so little prominence in popular historical literature and cinema. The commonly held narrative runs as follows: people gathered at the Bagh on 13 April 1919 for an anti-Rowlatt Act meeting; many amongst them were outsiders who had come to Amritsar for the Baisakhi festival. Dyer decided they had broken the law, gathered his troops and fired upon them. Hundreds died during the firing, and many jumped into a well at the Bagh while trying to escape the bullets. The dead included women and children.

This basic narrative is correct but there are some fallacies. To begin with, the meeting was attended mainly by residents of Amritsar. Due to the restrictions prevalent at the time, it would have been difficult for large numbers of outsiders to enter the old walled city. Even at the time, it was estimated that no more than 25 per cent were from outside. No one jumped into the well—they fell in by accident while fleeing the shooting, as it did not have a rim around it. And it is very likely that the massacre was a carefully planned one, not spontaneous as has often been made out. In all likelihood, no women were present.

What I have tried to do in this book is to piece together what actually happened on 13 April 1919 as well as before and after, using mostly the words of the survivors and recorded statements describing those terrifying events. Also, as far as possible, I have used Indian sources and viewpoints because for far too long (with a few exceptions), this narrative has been told by Western historians.

This book is a homage to the people of Punjab who, one hundred years ago, were humiliated, tortured and killed under the pretext of martial law. The period ranged from two months in some districts to over four months in others.

During this reign of terror, people were whipped, bombed, incarcerated, forced to crawl, starved, beaten, caged—and even summarily executed. However, the combined atrocities led to a turning point in the freedom struggle; it brought all the anti-British forces together for the first time. Not only were Hindus and Muslims seen together, joining hands against the British, the impact of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre spread through Punjab—from Amritsar to Lahore to Gujranwala—and to other places across India.

The events before the massacre also demonstrate the emerging importance of Punjab in the freedom struggle. These were still early years and there was no collective effort against the British. In terms of political leadership, this narrative is dominated by a few leaders working in their individual capacities and not as leaders of the Congress Party, which was the dominant party at the time. It was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, then not yet a member of the Congress Party, who was responsible for organising the people by deploying the tool of protest he termed ‘satyagraha’, against the Rowlatt Act. The massacre on 19 April was part of a policy of oppression unleashed by O’Dwyer against the frequent ‘hartals’ or the Satyagraha Movement.

The question is, where did the widely accepted narrative of Jallianwala Bagh originate from, when the reality was so much more complex? How is it possible that so many of us are unaware that aeroplanes were called in to bombard Amritsar and Gujranwala (now in Pakistan) and machine guns were turned on protesters?

Hundreds of people, including schoolboys, were publicly whipped in Amritsar and Lahore for small transgressions such as walking two abreast on a pavement or not salaaming a British officer. In Kasur (now in Pakistan), people were held in open cages.

In fact, the civil administration of Punjab had already declared Amritsar a war zone, when the massacre took place at Jallianwala Bagh, and regarded the residents as their enemies. All of this paints the massacre in a completely different light.

This book begins at the point when Amritsar was declared a war zone around 11 April, because the reader must understand the claustrophobic conditions which the residents of Amritsar were living in at the time. If we obliterate the sacrifice of those who were at the Jallianwala Bagh (by assuming that they were there, accidentally, for the Baisakhi festival), we also continue to disregard the humiliations that the survivors had to endure. Some of those frightful conditions were already in place before the mass murder took place….

*

A State of War

Baisakhi, 13 April 1919, Amritsar

Two days before the festival of Baisakhi, the city of Amritsar had been declared a war zone by the British administration in Punjab. The mood was sombre. Fear was writ large on many faces. People felt trapped inside the city, as there was a guard at almost every exit. Rich or poor, it was impossible for them to leave without written permission, and in the strained circumstances, such permission was unlikely to be forthcoming. Since the satyagraha against the Rowlatt Acts was still ongoing, the resulting hartal meant that food and daily supplies were becoming scarce. News from the outside world barely trickled in and censorship disallowed any news from leaking out.

Even those who considered themselves close to the British rulers felt the sudden icing up of the relationship. The British were upset and they had to express their anger in every way possible. The feelings of the people of Amritsar were irrelevant. If at any time they had imagined that they could get political and social equality, now all they experienced was rejection. Indians were being clearly shown that they were a subject race. If they tried to resist or fight against the changed environment or assault a European, the full might of the British Empire would be brought to bear against them. The army had been called in and there were daily threats that the city would be bombed. The remains of buildings, still smouldering in the aftermath of the recent riots and shootings, bore the scars of a bloody battle.

On the morning of Baisakhi, Sunday, 13 April, the old walled city was unnaturally tense. Those who had come from neighbouring villages and towns expecting a colourful, festive celebration had to struggle through the twelve city gates. Guards posted at some of the entrances and exits checked their luggage for lathis or any other weapons. The violent incidents of 10 April continued to be talked about and there were apprehensions of impending reprisals—reinforced by the heavy presence of the army. Memories of turbulence were alive everywhere.

Just outside the Hall Gate of the old city was the railway bridge, where on 10 April, protesting residents of Amritsar had been wounded and killed. They had been trying to cross the Rubicon which divided the ordinary people of Amritsar from the Civil Lines and cantonment area. On the other side of the bridge was where the white sahibs, and more specifically, the British Deputy Commissioner, lived. The unarmed protestors sought desperately to meet him.

The old city, on this side of the bridge, with around 160,000 residents, was congested and criss-crossed by narrow lanes, including the area that contained the famed Golden Temple. This was in sharp contrast to the large well-planned bungalows, surrounded by broad roads and gardens, which lay on the other side of the bridge. The balance of power between the ‘natives’ and their rulers was maintained by this sharp distancing. Most British officers and their families lived in the cantonment area; however, some Europeans had set up thriving businesses and banks in the old city, recognising its strategic commercial importance.

Excerpted from Jallianwala Bagh, 1919, The Real Story; Published by Westland Books